„Nein, ich nehme keine Drogen, ich nehme Bücher“, sagt die namenlose Ich-Erzählerin in Ingeborg Bachmanns „Malina“. Und wer könnte von diesem Roman aus dem Jahr 1971 anderes behaupten? Bachmann schrieb „Malina“ als „imaginäre Autobiographie“. Wie sie ist die Erzählerin eine Schriftstellerin mittleren Alters, die in Wien lebt, in der Ungargasse im dritten Bezirk, ihrem „Ungargassenland“, in dem es „nichts zu besichtigen gibt und man nur wohnen kann“, wie es eingangs heißt.

Um diese Fakten herum wird eine erratische, von verschiedenen Männern bevölkerte Szenerie psychologischer Intensität errichtet. Da ist Ivan, der jüngere Geliebte, dem die Erzählerin in pathologischer Hingabe verfallen ist. Da ist ihr Gefährte, der Militärhistoriker Malina, mit dem sie zusammenlebt. Und da ist der Vater mit der NS-Vergangenheit. Seine missbräuchliche Brutalität sprengt den Roman in der Mitte, wenn sich der äußere Schauplatz nach innen verlagert und es zu unerhörten Qualen kommt.

Politische Sensibilität

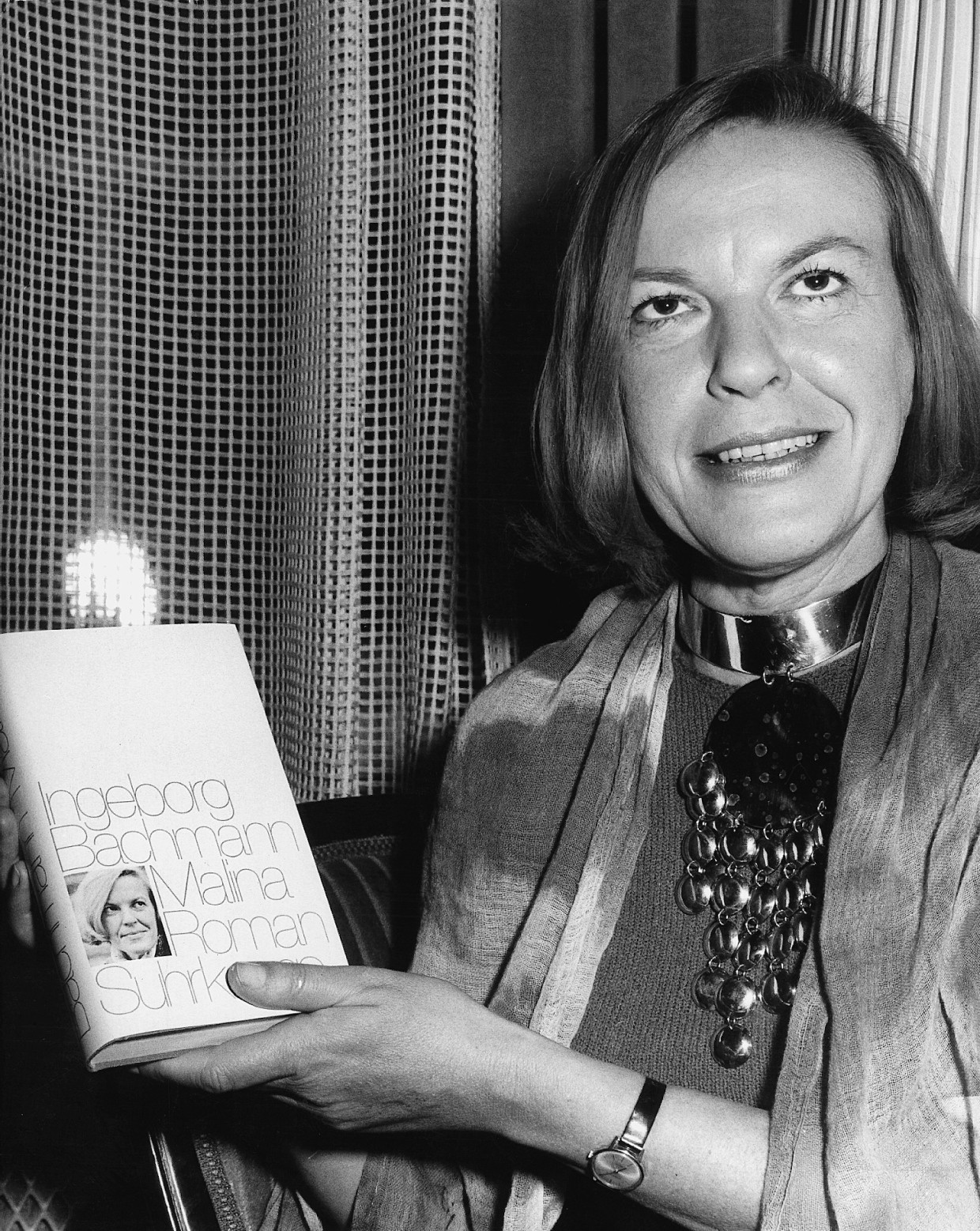

Ingeborg Bachmann zählt zu den bedeutendsten und engagiertesten Schriftstellerinnen des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. Sie wurde 1926 in Klagenfurt geboren und starb mit 47 Jahren nach einem Brand in ihrer Wohnung in Rom. Ihre politische Sensibilität wurde vor allem durch die Zeitzeugenschaft des Nationalsozialismus und der Schoa geprägt. Ihre literarischen Figuren stehen fast immer im Konflikt mit der Gesellschaft, sei es durch die Ordnung herausfordernden Liebesbeziehungen oder die quälende Suche nach Wahrheit und Selbstbestimmung.

Von ihrem ersten Gedichtzyklus „Die gestundete Zeit“ bis zu ihren späten Werken wie der Erzählung „Simultan“ oder eben dem ein Jahr früher erschienenen Roman „Malina“ begreift Bachmann Sprache nie nur ästhetisch, sondern immer auch politisch. Die Worte werden zum Instrument, um Macht, Kontroll- und Gewaltverhältnisse bis in die zwischenmenschlichen Beziehungen hinein zu zementieren. Und weil der dichte, poetische Bachmann-Sound, komponiert aus rätselhaften Monologen, gestörten Telefonaten, Albträumen und Märchen, vielfach fragmentarisch bleibt, in andere Sprachen übergeht oder in Musiknoten, wird das Geschehen nur immer noch zerrissener.

How can violent experiences, fears and hopes be represented beyond phrases? This is the basic question behind which Bachmann's postulate is: “The truth is reasonable for people.” This applies above all to the examination of the Austrian post-war society and its involvement in the Nazi era. The question of the responsibility of the individual and everyone else is at the center of the novel. “If we had the say, we would have the language, we would not need the weapons,” Ingeborg Bachmann formulated a few years earlier in her Frankfurt poetics lecture, which she does literally here.

“Malina” is the first part of the unfinished “death types” cycle and not very easily accessible prose. Like many existential works, the novel has many digestive depths and stimuli, and you have to learn to find your way around. In the first part, the narrator spends a lot of time waiting for Ivan and writing letters that tear her again. In the second, the disturbing main part, she hallucinated from war, fascism and the father figure, who acts as a preacher, analyst and SS man. In the desecration and existential threat to the daughter by the father, tolerated by the mother, all types of killing are played through: “Credit in a corner, without water, I know that my sentences are not left and that I have a right she.”

It was murder

In the third and last part, she talks to Malina, among other things, about a postman who has obtained what he was supposed to do, and finally finds death through her symbolic disappearance into a crack in the house wall. “It was murder.” The famous last sentence of the novel also affects the process of writing, which is no longer able to catch an unfulfilled life.

The examination of the legacy of National Socialism is primarily symbolic and in the subtext, not least through the psychological constitution of the protagonist. 1945, a present that is shaped by silence and repression.

What Ingeborg Bachmann drove to write was the belief in a utopia that she naturally knew that she would never become a reality. In this sense, “Malina” is less a narrative with a concrete action, but the accumulation of many stories: a crime story, but also the story of female subjectivity and the trauma of male violence, the nightmare of a war that tears a century, and the story of The impossibility of love between man and woman and the decay of words and meanings.

Written more than fifty years ago, the novel faces the Nazi heritage and the difficult reorientation in the post-war period with its issues of identity, gender and violence again of the topicality. The first-person narrator, who acts out of a crisis-like state, is no less threatened in its existence than the society that surrounds it, while in the relationships between the male characters the balance of power of the historical context is reflected.

The destructive man

At Bachmann, social violence always begins in private. That is why there is always war in the novel because it begins in the little one and also exists in peace. The relationships between men and women, indeed between people in general, are always violent at Bachmann. According to Bachmann's reading, the destructive and destructive is an integral part of being human. For the author, every democracy and every attempt to live together – both the sexes and society – are threatened by violence per se, and it requires the very highest effort to be able to live in something like peace at all.

Therefore, the torn in the novel protrudes beyond the personal crisis and becomes a symbol of a politically and socially estranged present, which is characterized by the unprecedented experience of the past as well as the political chaos and the moral confusion of the present. The disease of the narrator, her signs of schizophrenia become insignia of time with regard to questions of guilt, responsibility and identity. By leaving a gap between personal and social catastrophe, Bachmann also denies her heroine the chance of healing.

Violence, silence, repression

The experienced violence, the silence and the displacement devastate the interior of the figures as a toxic heritage and protrude into the collective like an ulcer. Silence about the past finds its most direct expression in the male figures. Both – Malina and Ivan – are confronted with history in their own way. In Malina, the dominant man-controlling man, continuity becomes tangible to Nazi violence. As a overpowering figure, he becomes the representative of a system of oppression, which the narrator is looking for.

“Malina” is the classic by Ingeborg Bachmann, who may put the mind more tested than other works by the author. Nothing soothes in this prose, and nothing is secured, not even the profession of the narrator, who is crossed out and overwritten twice in her passport. And whether the men really exist or are only reflecting the narrative ego – “I don't want to mislead Ivan, but it never becomes visible to him that I am twice. I am also Malina's creature ” – also remains unclear.

With its long sentences, which sometimes run over an entire side, as well as the echoes and rhythms that suggest coherence, where there is none, the novel fulfills a task that it has declared himself impossible: an injured person from the rubble Bergen. “Malina”, originally planned as an overture for the “type of death” cycle, should remain her only novel, which was completed and published during his lifetime, due to the early death of the writer.

The other parts, “Requiem for Fanny Goldmann” and “The Franza case”, remained fragments and were published postally. “Malina”, however, is the challenge and the fascination of the last hand, which has been encouraging new generations of readers for more than fifty years to explore his secret that Ingeborg Bachmann has nestled in almost every word.