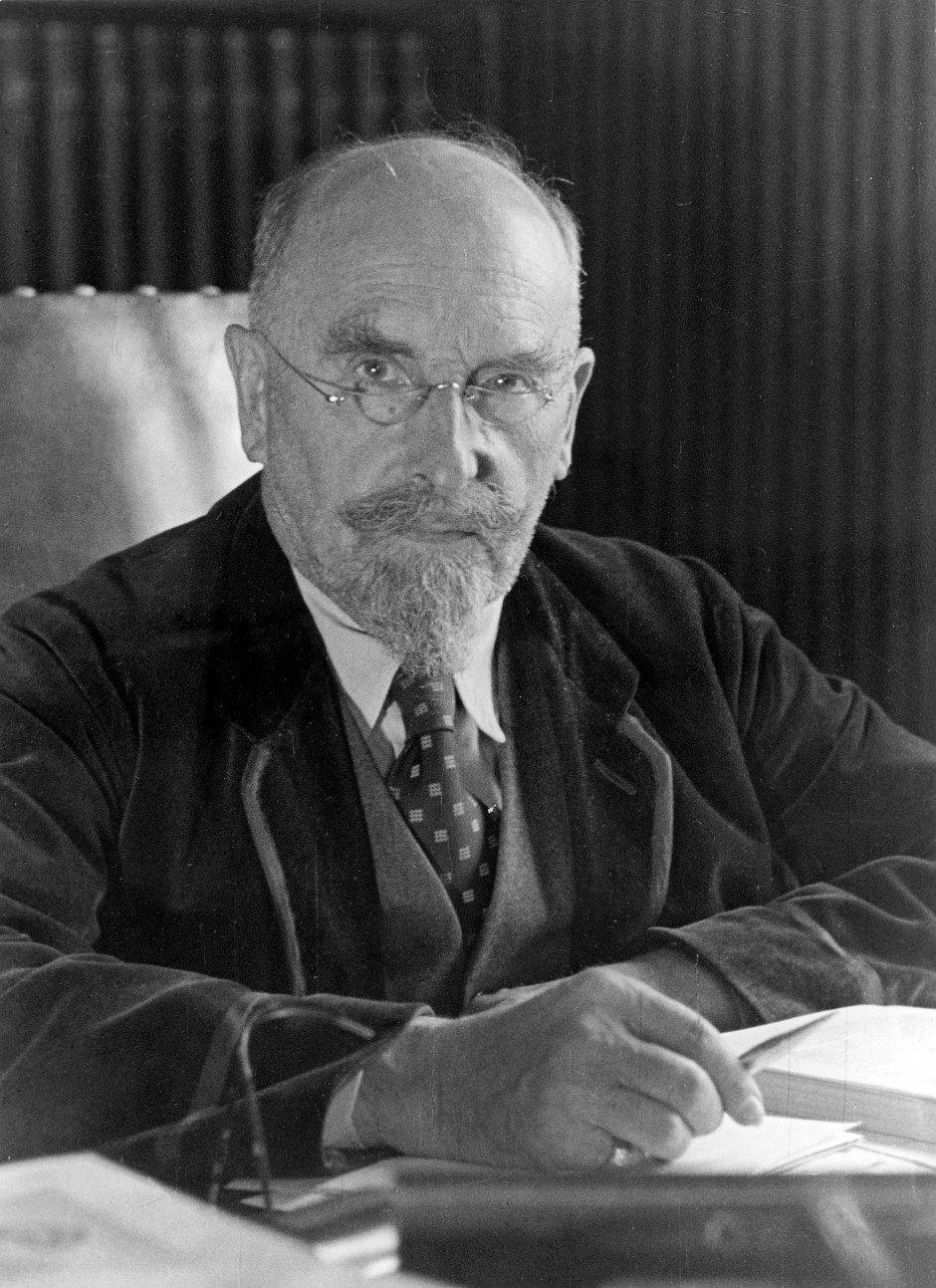

Lecture hall 22.2 has lost its namesake. A large sign has been hanging a few meters next to the entrance to the auditorium, overwritten with “Franz Volhard: Light and Shadow of a University Teacher in Frankfurt”. Among them is a detailed text that explains why the university clinic no longer wants to decorate its lecture hall with the name Volhard. The well -known doctor's bust has already been banished to the Institute of History of Medicine.

For the critical processing of Volhard's role, especially in the post -war period, university medicine and the Department of Medicine took longer than others. As early as 2023, the German Society for Nephrology renamed its Franz Volhard Prize for outstanding services because it not only criticized the attitude of the doctor “to the misconduct of colleagues”, but also that he had disregarded medical-ethical principles at the time at the time of 1940.

No active participation, but incorrect consideration

It was known for a long time that Volhard was relief for his colleague Wilhelm Beiglböck in the Nuremberg trials, who had administered concentration camps in test series. Years later, what became clear at the time was confirmed: that Volhard evaluated medical knowledge from human experiments higher than the suffering of the subjects concerned. Although he himself was not involved in such experiments, he had a colleague, Werner Catel, granted by his attitude after the war. With fatal episodes for four children.

Werner Catel had tested a not approved medication of children in the “Mammolshöhe” healing site at Königstein. In children, there was a risk of fatal side effects in the room, but Catel continued his “healing tests” with the substance of minors – without inauguration. As two children died, two employees of Catels, the Santo couple, turned to higher places. In their complaint, they raised far -reaching ethical questions: Can a doctor use a new medication that is potentially fatal if other funds with lower side effects are available? Can he try it out in otherwise hopeless cases or even on those who are already on the way of improvement? And above all: Can you experiment with children without the consent of the parents?

Franz Volhard, a long -time acquaintance of Catel, should make an expert opinion on this complaint. Volhard expressly approved Catel's procedure in it because his goal was to find an effective medication against the devastating child's tuberculosis. Just as if the purpose of every means is sanctified. The couple Santo discredited Volhard in his omissions. The doctor, on the other hand, did not answer the ethical questions raised in the complaint. Catel then continued to work on the Mammolshöhe, and four children died in the following.

Thinking about the limits of research

Volhard thus ignored the Nuremberg Codex, ethical guidelines for doctors who had come from the experience with human trials on concentration camp prisoners. According to this, medical research requires the voluntary approval of the patients and prohibits unnecessary agony or risk of death. No completely new rules, the Reich Ministry of the Interior had already issued similar guidelines, which Volhard also ignored.

The Gießen medical historian Volker Roelcke, who had already developed a study on the attempts at the Mammolshöhe on behalf of the Hesse State Welfare Association, was now also advisable to the University Hospital Frankfurt to historically classify the role of Volhard.

While the medical services of the internist are undisputed, his attitude towards medical research is criticized. In dealing with the historical person, there can also be an impetus to think about the limits of research, according to the medical director of the university hospital, Jürgen Graf: “Without clinical studies, there is no medical progress, they are of great value for us.” However, patients would only make themselves available for studies if they could be sure that the processes are carried out correctly and according to ethical rules. “There must be trust between patients and doctors.”

Because he has disregarded these rules, Volhard no longer serves as a model for today's medical students, says Graf. Stefan Zeuzem, Dean of the Medicine Department of the Goethe University, adds: “We have to deal with Volhard's past. Just taking the name down is not enough. ” And the lecture hall? From now on he has to use his unadorned name 22.2. be satisfied. There is no search for a new namesake, according to the university clinic.