An A-list of researchers from across USC is building a dementia cost model that will generate comprehensive national, annual estimates of the cost of dementia that could benefit patients and their families, thanks to a five-year, $8.2 million federal grant from the National Institute on Aging.

A firm grip on the costs of the disease could assist families living with dementia with planning their budgets and support needs, inform treatment and caregiving options, and help shape health care policy.

“We currently have estimates for a particular set of costs, but we’ve learned those estimates don’t encompass nearly all the costs to the person with dementia, their family and to society,” said Julie Zissimopoulos, a professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy and the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics, who is leading the project. “Everything about this disease affects the family’s pocketbook.”

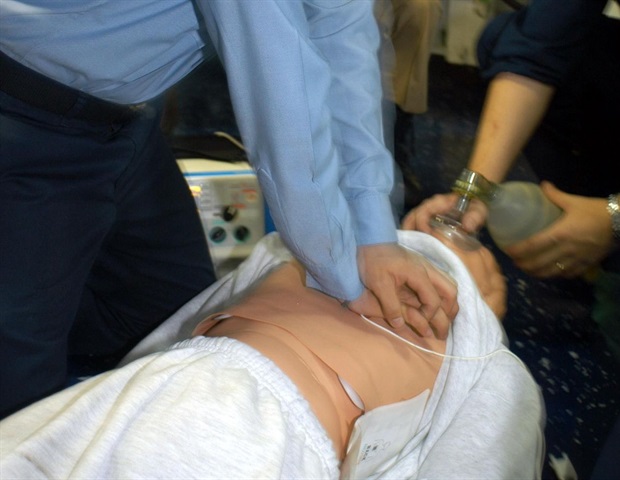

Dementia costs can be catastrophic for families, depleting savings and pressing caregivers to leave their jobs. The condition imposes a staggering economic burden on the United States as a whole. This year, total health care and long-term care costs for individuals with Alzheimer’s or other dementias are projected to reach $360 billion, and may soar to nearly $1 trillion by 2050, the Alzheimer’s Association projects.

“Other consequences may include caregivers’ lower retirement savings or limited ability to send their children to college,” said project advisor Maria Aranda, a professor at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work who studies the impact of Alzheimer’s on Black and Latino families. “In turn, this leads to an intergenerational transmission of inequality and financial vulnerability for families of persons with dementia.”

The tool, known as a “dynamic microsimulation model,” will incorporate multiple data sets including data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and national surveys on aging Americans such as the Health and Retirement Study. The model will account for costs across a range of disease stages, including those accrued by the person living with dementia, their care partners and caregivers, and even their payers. In addition, the model’s estimates will adjust for prevention and treatment innovations.

The research team is co-led by Dana Goldman, who will become the director of the new USC Schaeffer Institute for Public Policy & Government Service on July 1 after having served as the dean of the USC Price School for the past four years. The A-team also includes experts from:

- Keck School of Medicine of USC.

- USC Alfred E. Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

- USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

- USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

- USC Viterbi School of Engineering.

“Once you factor in the social costs of Alzheimer’s -; how it affects family, caregivers and others -; you quickly realize it is not just an illness but a social epidemic,” Goldman said. “This project will help amplify the importance of finding treatments that forestall the devastation.”

Patients and caregivers are among the experts who will advise on the project. Other advisors include representatives of the Alzheimer’s Association, UCLA, the University of Pennsylvania and the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

USC Viterbi scientists will design an interface so that the tool, which will be publicly available, is user-friendly.

In addition to providing up-to-date and comprehensive annual estimates, researchers will be able to calculate, for example, the social and economic impact of drugs that treat the neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with advanced dementia -; and keep patients out of hospitals and emergency rooms. The tool might also measure cost savings provided by a new drug with modest benefit, but which delays by two months the expense of 24-hour care.

“Leqembi is a great example. It’s a new FDA-approved treatment for early-stage Alzheimer’s; we have data from clinical trials that informs patients and the health care providers about safety and efficacy, ” Zissimopoulos said. “But these data are not informative about the other outcomes patients and their families care about including quality of life impacts that may result from this slowing of cognitive decline. And we want to know about not just the 18 months of the clinical trial, but we want to know about them for 10 years, for 20 years.

“With the infrastructure that we’re building, we’ll be able to understand better what is the value and for whom.”

Source:

University of Southern California