In a recent research briefing published in Nature Medicine, researchers highlighted the significance of air quality in preserving immune health over the human lifespan, especially lung-related immunity, owing to the lungs’ continuous exposure to the environment.

Background

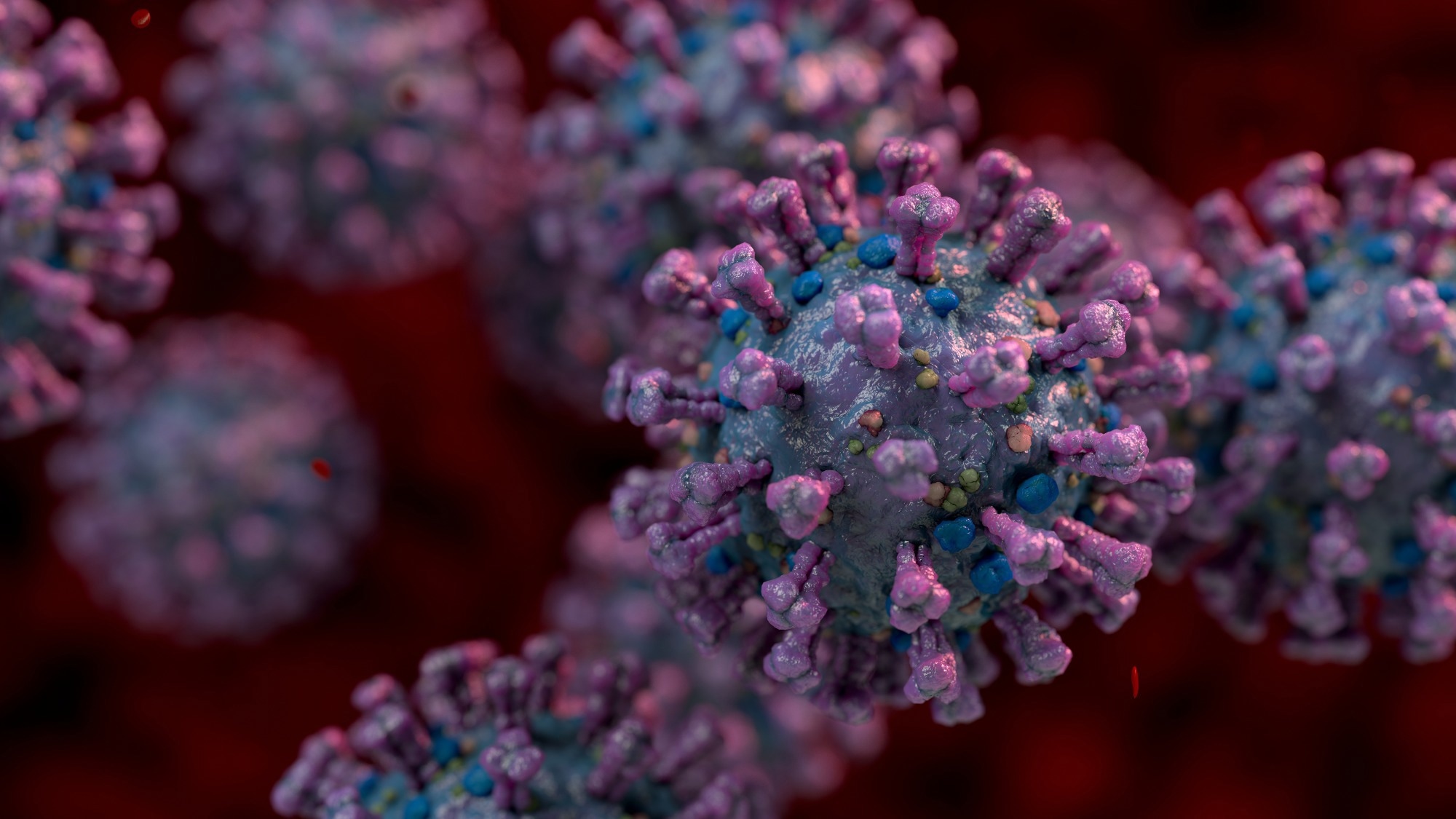

Aging exacerbates disease susceptibility, a harsh reality that surfaced during the unprecedented coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. However, older individuals are not only more prone to infection by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), but they are also prone to other lung diseases, for example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lung cancers.

As people age, age-related changes in immune cells and subsequent systemic inflammation functionally impair their acquired immunity, likely increasing their susceptibility to disease(s). Since the immune system resides in mucosal and lymphoid tissues, the effect of increasing age on local immune responses in these regions needs detailed evaluation.

An improved understanding of the physiological mechanisms that exacerbate disease susceptibility in the elderly could help reduce healthcare costs associated with diseases in a rapidly aging world population. Notably, individuals in the age group of 60 or more are consuming a large proportion of healthcare funds worldwide.

About the study

In the present study, researchers obtained lymph node (LN) samples from human organ donors from varying age groups to investigate the effect of particulate matter on their immune cells. Since they observed pronounced effects of air pollutants on LNs in the lungs compared to LNs in the gut, they used quantitative imaging to visualize LN architecture across all LN sites. Further, they used functional and cellular assays to analyze the effect of aging on LNs.

Study findings

The researchers noted an accumulation of black particulate matter in lung-related LNs that increased substantially in samples of individuals who were over 40 years. On the contrary, gut-related LNs remained beige-colored and had no black particulate matter.

Particulates in lung-related LNs remained confined to a specific population of macrophages nested in the T cell expanse (not within follicles). These macrophage subsets displayed functional alterations, such as impaired cytokine secretion, reduced activation, and a markedly reduced phagocytic potential. Intriguingly, macrophages with no particulates harbored inside the same LN did not display any functional alterations. Finally, the researchers also found that particulate accumulation in lung-related LNs led to age-related changes in the structural integrity of LNs, due to the disturbances in the lymphatic drainage and B cell follicles.

Together, the study results demonstrated the direct and detrimental effects of inhaled particulate matter on acquired and innate immune processes that accrue over time in the lymphoid system responsible for immune surveillance of the respiratory system, especially the lungs.

When lung-related LNs become clogged with particulate matter, their ability to filter toxins, hazardous antigens, and microbial pathogens diminishes substantially. The outcomes worsen with age, which, to some extent, rationalizes the increased risk of respiratory diseases in the elderly compared to the younger population.

Conclusions

The current study offered new insights into how environmental pollutants interact and alter the human immune system by examining LN samples rather than blood samples from deceased organ donors of varying age groups.

Future studies should explore the mechanisms specific macrophages in the lung-related LNs employ to contain particulates within. Studies should also investigate whether these macrophages are LN residents, derivatives of lung macrophages, or migrate to lungs from other LN sites (e.g., mucosal sites). More research is also warranted to investigate the effects of particulate matter accumulation on pathways other than the phagocytosis pathway in the LNs that wipes out cellular debris and microbial pathogens.

Furthermore, the study should motivate more research exploring the effects of carbon emissions and other types of pollution on the human immune system.