Der Zauber der Kunst von Caspar David Friedrich ist unerschöpflich. Drei große Ausstellungen (und ein paar kleinere) gab und gibt es im Jubiläumsjahr, und jede erzählt eine andere Geschichte. In Hamburg war es die Geschichte eines Ahnherrn der Moderne, in Berlin das Epos seiner Wiederentdeckung und Kanonisierung um 1900. In Dresden, der Stadt, in der Friedrich vierzig Jahre lang gelebt hat, ist es die Geschichte einer Welt.

Wer dort den Sonderausstellungssaal im Albertinum betritt, einen von zwei Standorten der Ausstellung „Wo alles begann“, sieht auf den ersten Blick kein einziges Bild von Caspar David Friedrich. Stattdessen prangen an der Längswand dicht an dicht gut einhundertzwanzig Gemälde seiner Zeitgenossen: Gérards pompöses Napoleon-Porträt, Philipp Veits „Ecce Homo“, Johan Christian Dahls „Blick auf Dresden“, dazu Stücke von Richter, Carus, Blechen, Koch, Oehme, Schnorr von Carolsfeld und anderen. Es ist die Kunst der Salons, die Friedrich mied, die Malerei des Marktes und der Mode. Und es ist die Kunst, vor der er weichen musste. Ab 1820 sank Friedrichs Stern, bei seinem Tod zwanzig Jahre später war er fast vergessen, während die Nazarener, deren puzzlehafte Kompositionen er als „Trödelbuden“ schmähte und deren Bonbonfarben er mit Schminke verglich, den Geschmack des Biedermeier beherrschten.

The carpet of pictures roars at the viewer like a horizontal advertising column. But as soon as the noise has died down, the opposing voice can be heard all the more clearly in the five exhibition sections on the other side of the room. And one understands once again why Friedrich did not fit into any school or style of Romanticism, why he was a stranger even to his closest painter friends. It is enough to stand in front of one of the pictures from his late period, which are brought together under the heading “Luftschaften” (Airscapes), to step out of the hustle and bustle of the market and into another universe.

For example, the “Great Enclosure” from 1832 with its copper-colored and blue-gray reflections of the sky between the alluvial islands of the Elbe. Or the “Seashore in the Moonlight”, which Friedrich continued to work on after his stroke in 1835, one of the last paintings he completed: the horizon a sword of light between a dark blue, puffy sky and a blue-black coast, the reflection of the half-covered moon like scratched silver on the waves. Three sailing boats as moths floating towards the pools of light. Rilke called this “the interior of the world”, and Friedrich created this space with his brush, picture by picture, a hundred years before the “Duino Elegies”.

Of the three major Friedrich exhibitions, the Dresden exhibition has the most to offer, because this is where Friedrich's landscape lay, the Elbe Sandstone Mountains with their cliffs, forests and river valleys, which he began drawing shortly after moving from Greifswald in the summer of 1798. But this was also the location of the most famous German painting gallery of its time, and in this respect the exhibition in the Albertina curated by Holger Birkholz is truly pioneering.

Birkholz has meticulously linked the figure studies with which Friedrich filled numerous drawing sheets in his early days in Dresden with their models by Dutch old masters such as Ruisdael, Berchem and Philips Wouwerman and then followed the path of the figures through Friedrich's painting. For example, one sees how the elegant couple from Wouwerman's “Fishermen on the Beach” wanders through the painter's world in ever new disguises until they come to rest in the grieving parents at the entrance gate to the “cemetery” of 1825. Behind the open doors there is a fresh child's grave, behind which is a forest clearing strewn with crosses and steles in front of deciduous trees. Between the trunks the delicate, silvery outline of an angel trembles, carrying the child's soul to heaven.

Contrary to his usual practice, Friedrich did not finish painting the foreground of the picture. This is precisely why it is one of the discoveries of the Dresden exhibition: it points to a time in which the fragmentary will become an artistic medium, and combines this freedom with the confident painting style of the Old Masters. Friedrich's modernity, like that of the Surrealists, has a classical touch; it overcomes the visible world without destroying its forms.

Friedrich's second educational experience in Dresden, apart from the Dutch, was the art of his previous generation. Anton Graff, Adrian Zingg and Johann Christian Klengel had painted Elbe landscapes and Bohemian mountains, and the academy student from Greifswald absorbed their teachings and adapted them to his own needs. In the Kupferstichkabinett, the second stop on the Dresden exhibition, four gouaches are on display that Friedrich painted around 1802 in the Plauenscher Grund in the Weißeritz valley. They show the creator of the “Abbey in the Oak Forest” as a late Baroque idyllist. His swans swim neatly in the mill pond, the country road is enlivened by cows, and a glassworks bravely blows its coal smoke into the evening sky.

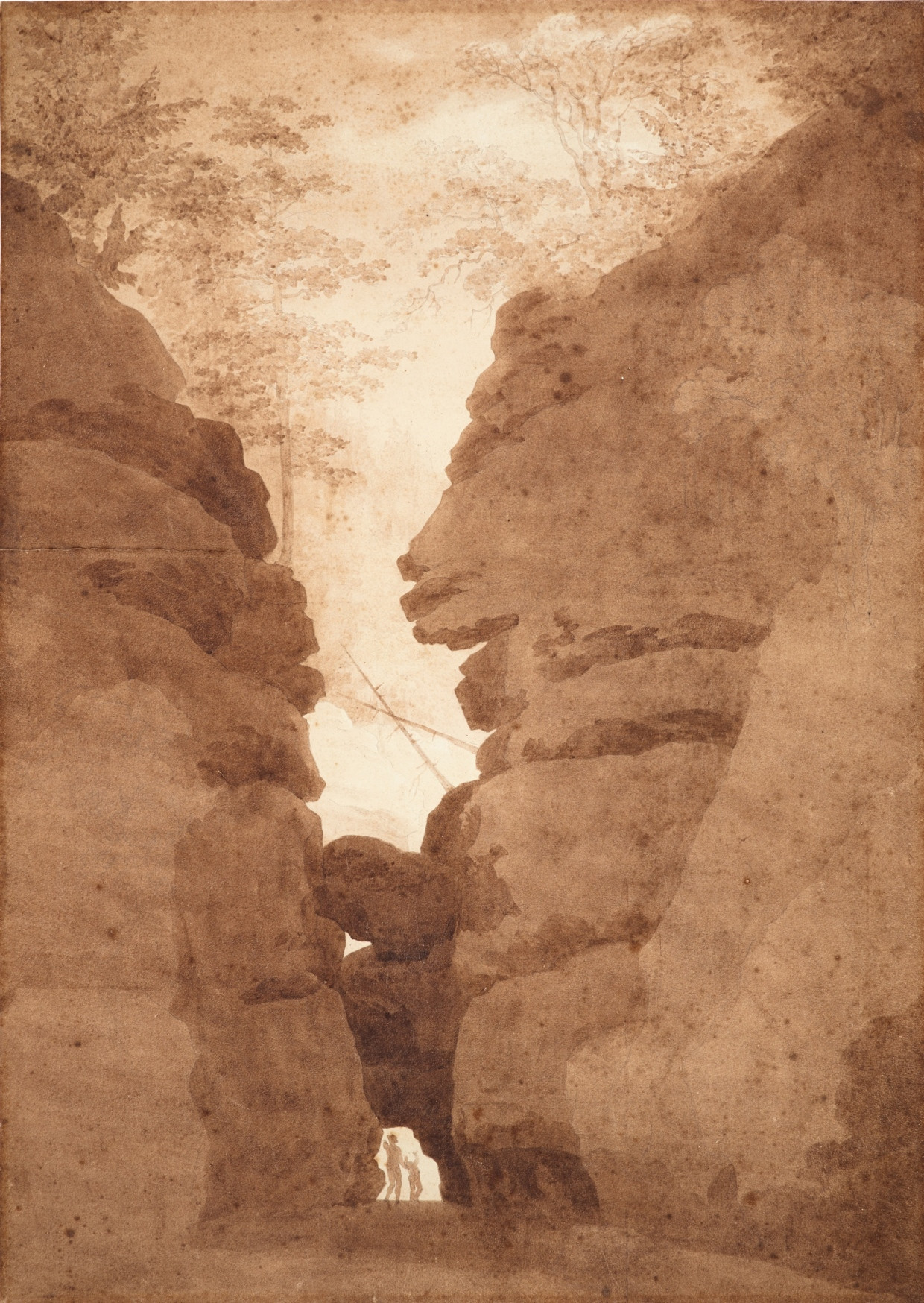

The revolution that the artist achieved with the Tetschen Altar and the switch to oil painting five years later only becomes really visible from here, and in Dresden you can follow it step by step. The Berlin Seasons Cycle still contains Rococo elements, but on Rügen Friedrich is already drawing landscapes without any pictorial decoration. In the Weimar Sepia Sheets and the Karlsruhe Sketchbook, which can be digitally opened in the Kupferstichkabinett, he finally finds his form. The towering spruces, the gnarled, leafless trees, the flat fields and the rocks floating in the mist become the letters of his painterly language.

And just as he copied figures from the old masters, he collected landscapes in Saxony and Bohemia. He found the ruins of the monastery of Eldena, transformed, in Altzella and Oybin near Zittau. In the Uttewalder Grund he drew rock gates and stones for his megalithic tombs, tree studies in the Tharandt Forest, and chains of hills in the Giant Mountains. Only his adopted home of Dresden remained as alien to him as a backdrop, as it was to his painter friends and rivals. The “Woman at the Window” obscured the view of the banks of the Neustadt. Behind the “Hill with Broken Field” from 1824, only the spires of the towers rose out of the morning mist. But if you look long enough, you can already recognize the ravens from van Gogh's “Wheat Field” in Friedrich's rooks.

One chapter that is neglected in both parts of the exhibition in Dresden (as in Hamburg and Berlin) is the political Friedrich. The painter, who fled to the forests to escape the war and to his studio to escape the street riots of 1830, despised the “royal servants”; the old German clothing that many of his figures wear was a statement against the class society of the Vormärz period. And “Hutten's Grave” once bore not only the name of the reformer, but also those of Arndt, Jahn and Görres. The painting hangs in the “Cemeteries” section of the Albertinum, but it could also have been given a different heading: “Protest”. There are still many stories to tell about the painter Caspar David Friedrich. Just as there are stories to tell about his art.

Caspar David Friedrich. Where it all began. Albertinum Dresden, until January 5, 2025, and Kupferstichkabinett, until November 17. The catalogue costs 36 euros.