Als der Maschinist das Tempo des Fließbandes mit einer Handbewegung erhöht, kann der neue Arbeiter – kleiner und schwächer als die anderen, aber erkennbar eifrig – das Soll nicht mehr erfüllen. Anfangs versucht er es, indem er den immer rascher vorbeischießenden Werkstücken hinterhereilt, irgendwann reicht auch das nicht mehr, und er wirft sich auf das Fließband, mit dem er im Getriebe der riesigen Maschine verschwindet. Der Kollege aber, der neben ihm arbeitete, ruft ihm hinterher: „He’s crazy!“

Dass die Kuratoren der Ausstellung „Modern Times“ zur Kunst der Zwanzigerjahre des vorigen Jahrhunderts gerade diesen Ausschnitt aus Charlie Chaplins gleichnamigem Film an den Beginn des Rundgangs im Freiburger Museum für Neue Kunst stellen, leuchtet sofort ein. Nicht nur weil die Sequenz eine Arbeitswelt darstellt, in der sich der Mensch den Maschinen anpasst und nicht umgekehrt, was im Verlauf der Ausstellung noch mehrfach zum Sujet wird. Sondern auch weil durch den Ausruf des Kollegen ein Bogen zu einem anderen Phänomen gespannt wird, das einen weiteren inhaltlichen Schwerpunkt in der Kunst jener Jahre liefert.

Nicht weit davon entfernt, die Kontrolle zu verlieren

Denn so, wie die Zwanzigerjahre hier beleuchtet werden, von den unmittelbaren Kriegsfolgen in der Weimarer Republik über die oft elende Welt der Arbeiter, die politischen Spannungen, die beginnende Emanzipation und Teilhabe der Frauen bis hin zum rauschhaften Gehabe der Neureichen, stellt sich immer auch die Frage, was eigentlich aus jenen wird, die nicht mittun können oder wollen.

Some of the artists now gathered in Freiburg find the answer to this by turning to the inmates of psychiatric hospitals, such as Conrad Felixmüller with “Soldier in the Madhouse” from 1918 – the man, much too tall for the narrow cot on which he kneels, has blood-red hands and an equally colored iron cross on his chest. Another man watches him through a window. The soldier turns his head with an impossible turn of his neck, his mouth is slightly open, as if he is shouting something to the viewer outside. One can hardly expect that the man beyond the walls will open the door back into the world for the energetic patient. Does the soldier even want it?

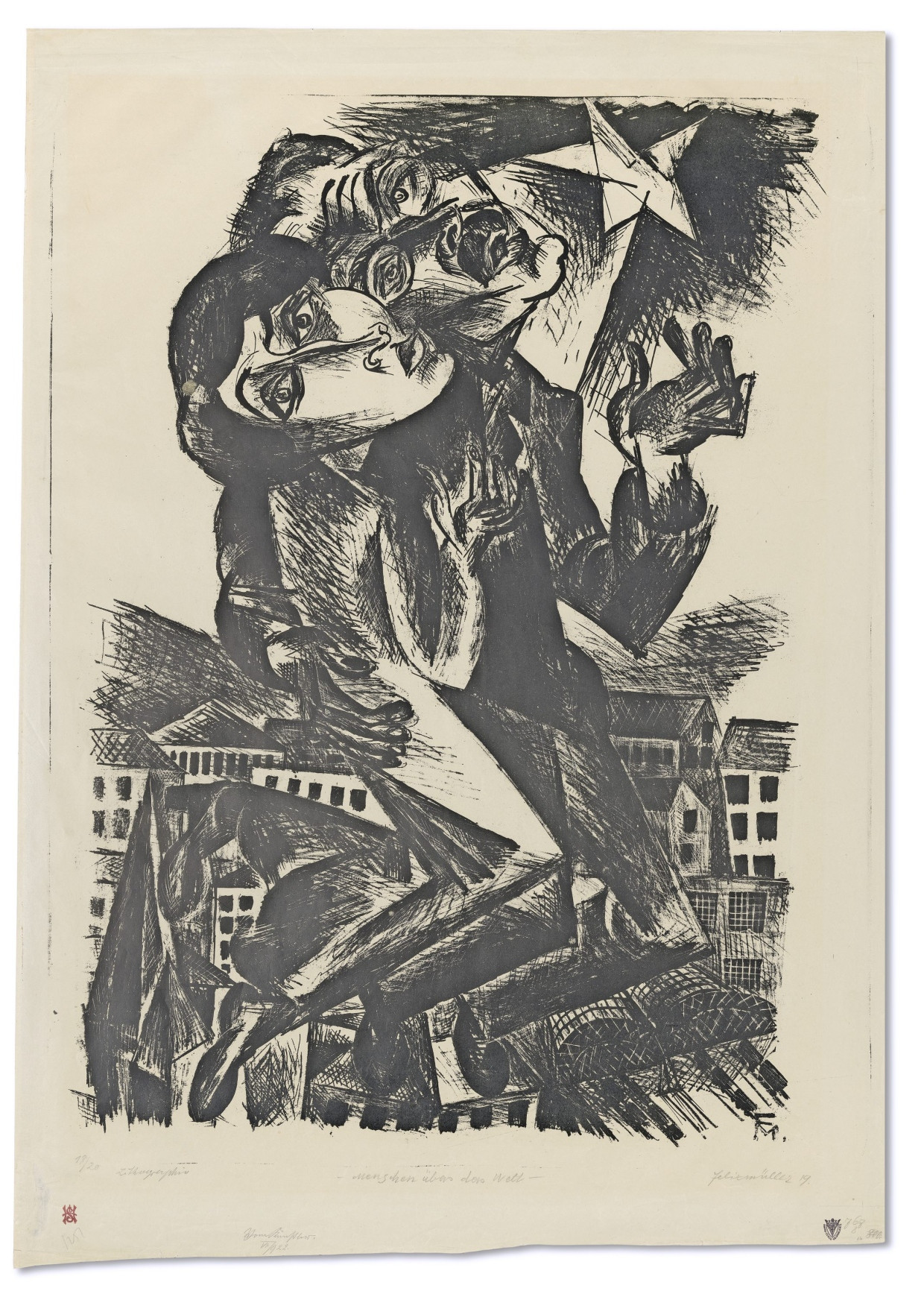

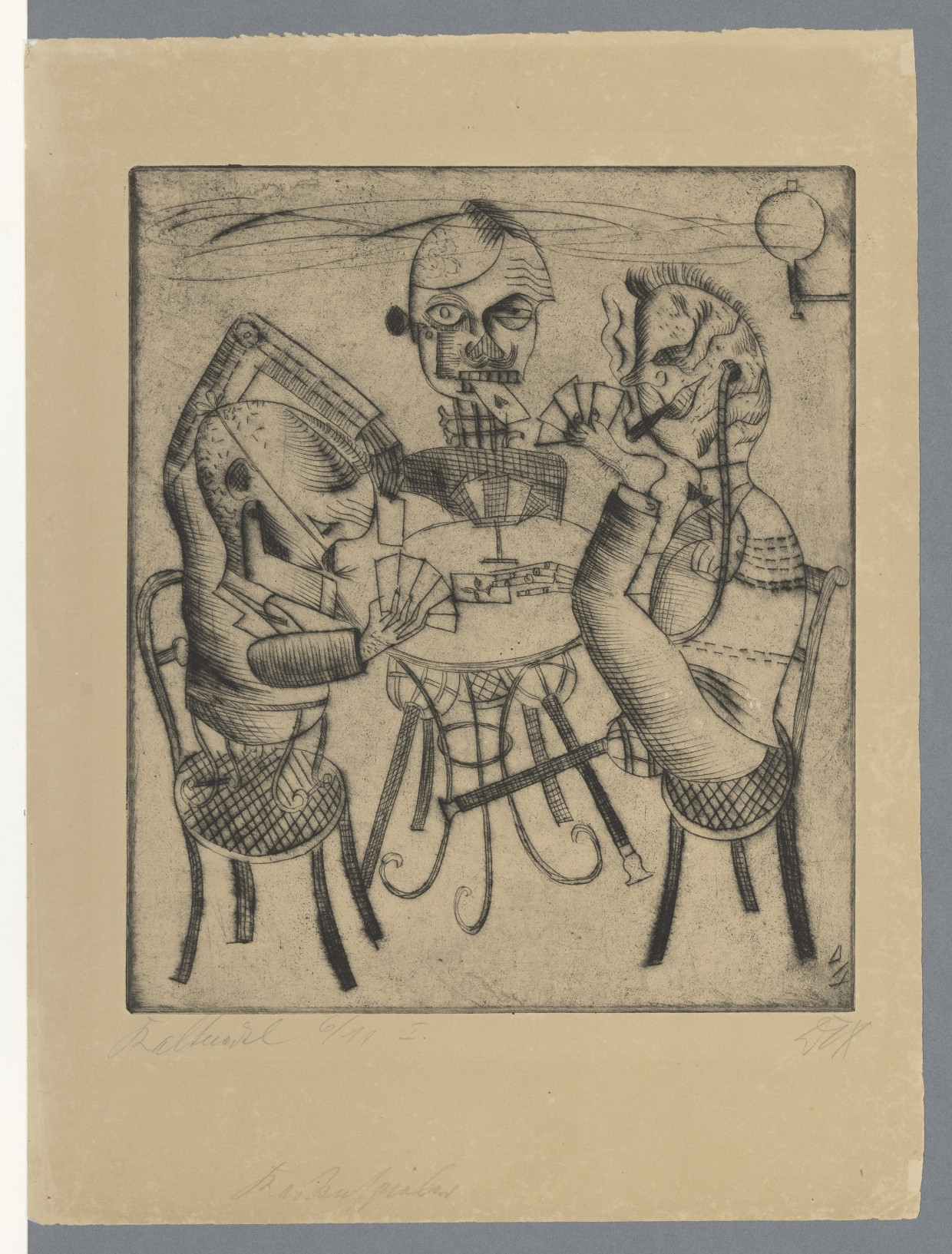

Other artists depict exactly that, such as George Grosz with his drawing “Ruckus of the Insane”, who transfers the action to the street, and in some of the pictures in this exhibition the protagonists, with their active facial expressions, do not seem to be in the face of the monstrosities they are witnessing far from losing control of yourself – for moments, perhaps for longer. It is the grotesque differences between poverty and obscene wealth of those years, the hunger that looks incredulously at the wealth on display, the misery of the war cripples, the dull faces of the workers in the coalfields, which Conrad Felixmüller drew in the early 1920s when he was his He preferred to use the scholarship that was supposed to take him to Rome to stay in the Ruhr area.

A centerpiece of this exhibition, which is mainly due to the rich loans from the Lindenau Museum in Altenburg, is the etching cycle “The War” by Otto Dix, published exactly one hundred years ago. It is presented entirely in its own room, fifty densely hung sheets, preceded by a trigger warning from the exhibition organizers because the various stages of decomposition depicted here are indeed gruesomely intense. Dix changes the perspective again and again, placing still lifes next to action-packed scenes such as the attack by the soldiers wearing gas masks, which shockingly resemble the skulls in other pictures.

Not everything is mysterious in this exhibition. It has moments of beautiful exuberance as well as evidence of social awakening, such as the artistic canonization of the murdered Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who let Conrad Felixmüller float into the sky with their arms wrapped around them. The same painter, whose works shape this exhibition in no small part, created “Workers' Procession at Night” in 1923, a work whose colors and flat figures carry all the ambivalence of the time, heavy baggage and confidence at the same time.

Finally, one focus of the exhibition is on children who are exposed to a disturbing world at an early age, in which they despair or even grow. And against which they protest like Elisabeth Voigt's “Little Drummers” from 1926. He sits in an empty room, beats the drum and screams, maybe he also sings, sways to the beat and tosses his hair. This is another way to defy the madness of the times. The boy reliably finds his audience, at least today.

Modern Times – images from the 1920s. Museum for New Art, Freiburg; until February 16th. The catalog costs 28 euros.