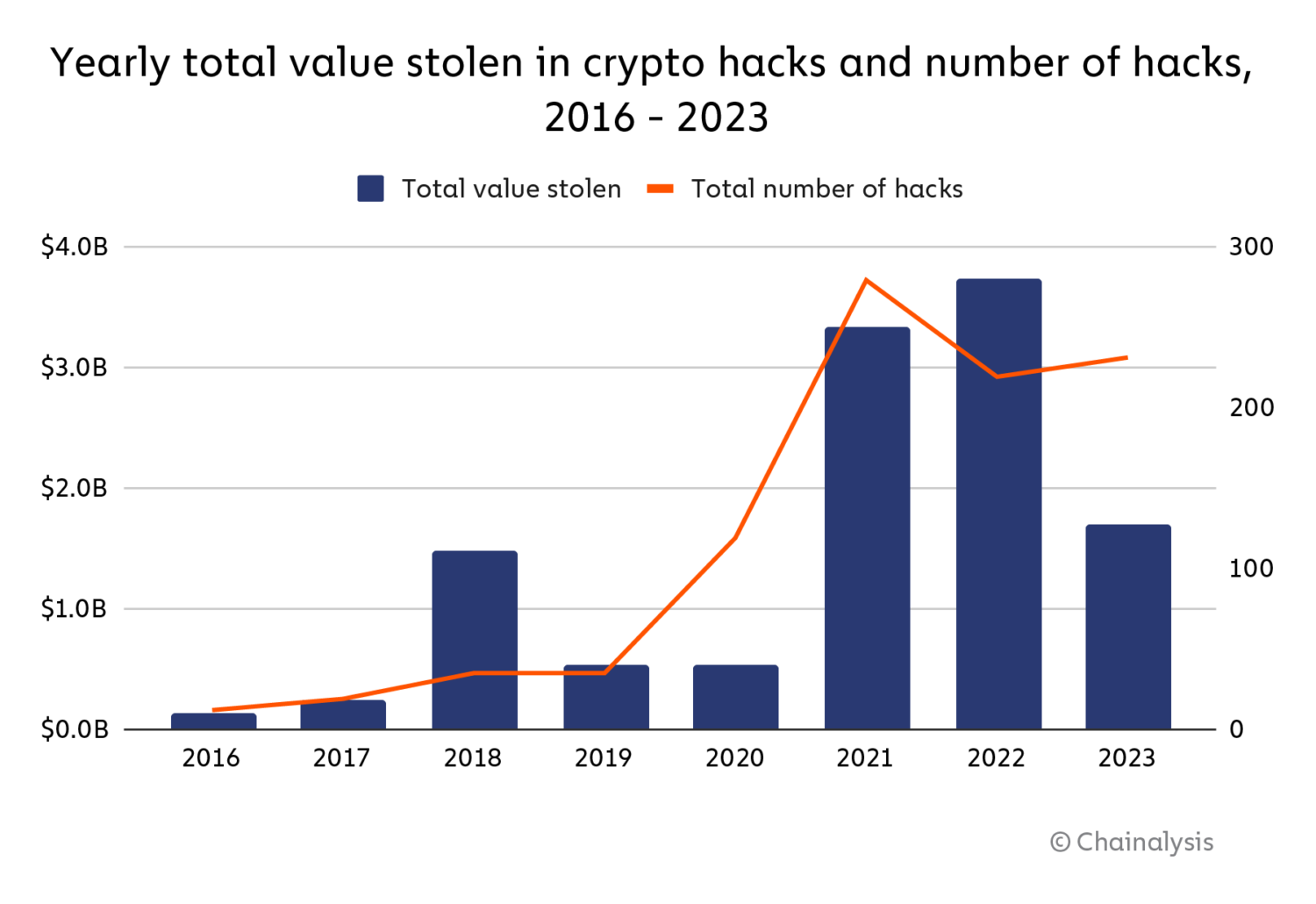

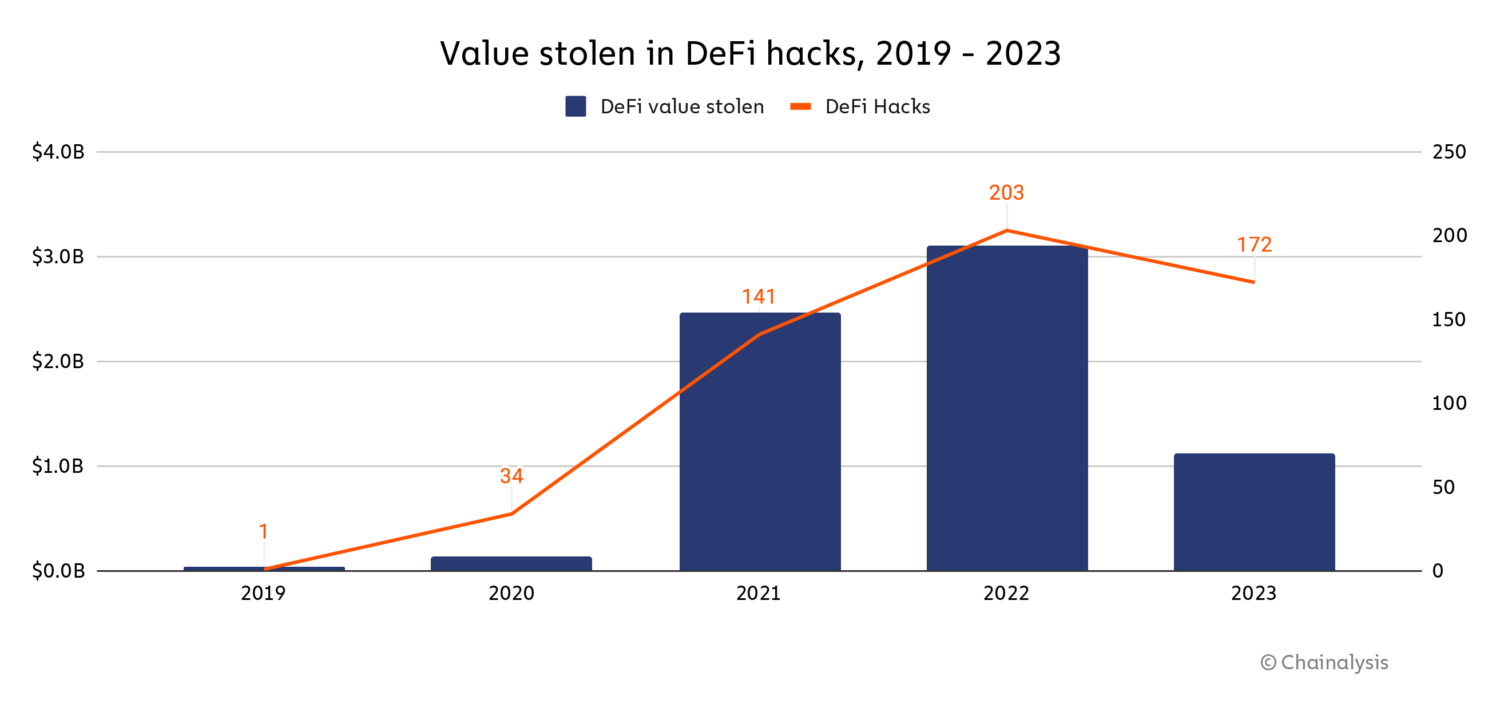

Over the last few years, cryptocurrency hacking has become a pervasive and formidable threat, leading to billions of dollars stolen from crypto platforms and exposing vulnerabilities across the ecosystem. As we revealed in last year’s Crypto Crime Report, 2022 was the biggest year ever for crypto theft with $3.7 billion stolen. In 2023, however, funds stolen decreased by approximately 54.3% to $1.7 billion, though the number of individual hacking incidents actually grew, from 219 in 2022 to 231 in 2023.

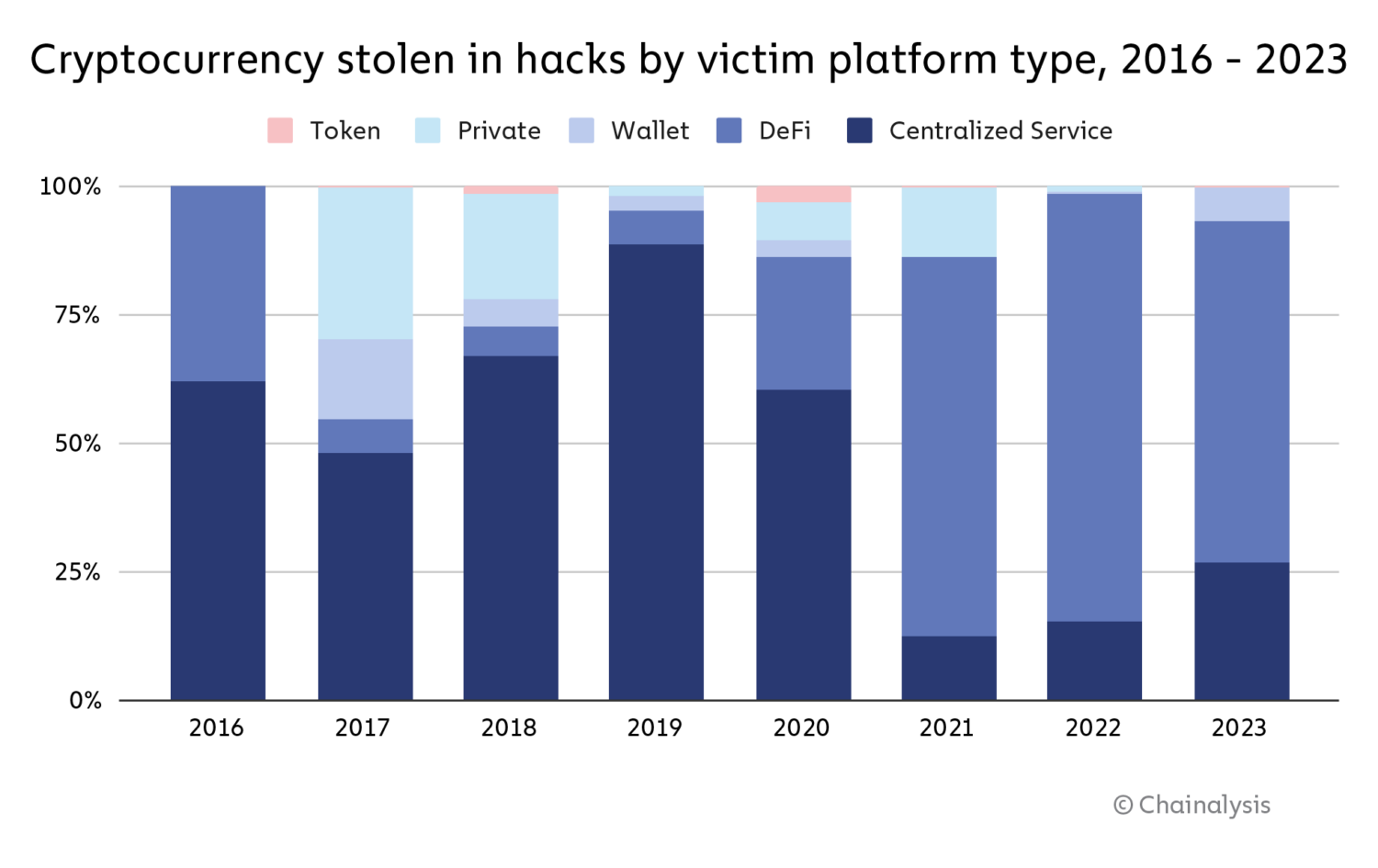

Why the huge drop in stolen funds? Mostly due to a drop in DeFi hacking. Hacks of DeFi protocols largely drove the huge increase in stolen crypto that we saw in 2021 and 2022, with cybercriminals stealing more than $3.1 billion in DeFi hacks in 2022. But in 2023, hackers stole just $1.1 billion from DeFi protocols. This amounts to a 63.7% drop in the total value stolen from DeFi platforms year-over-year. There was also a significant drop in the share of all funds stolen accounted for by DeFi protocol victims in 2023, as we see on the chart below.

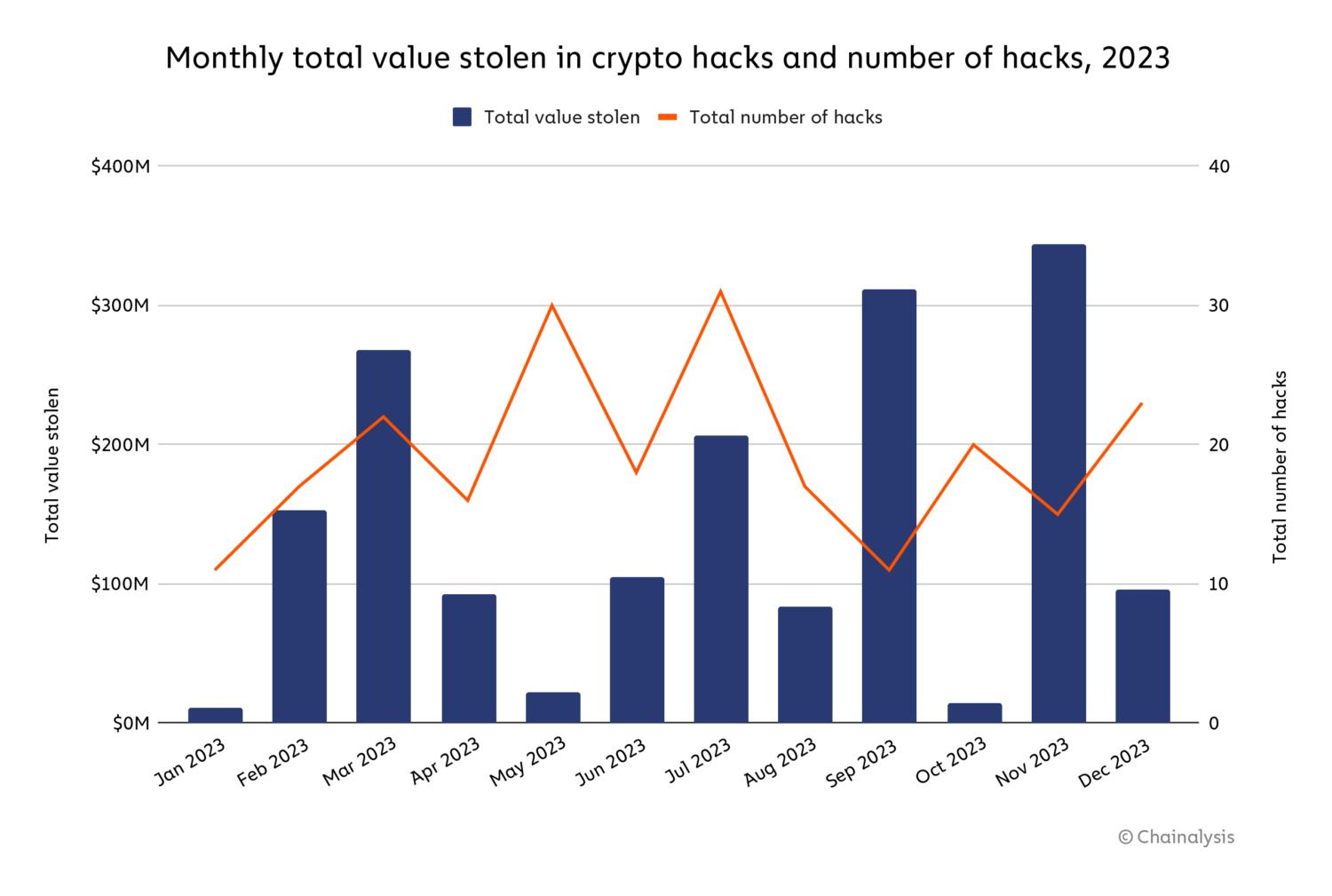

We’ll explore the possible reasons for the drop in DeFi hacking in greater detail later on. Despite that drop, there still were several large hacks of notable DeFi protocols throughout 2023. In March, for instance, Euler Finance, a borrowing and lending protocol on Ethereum, experienced a flash loan attack, leading to roughly $197 million in losses. July 2023 saw 33 hacks — the most of any month — which included $73.5 million stolen from Curve Finance. We can see the spikes driven by those hacks below.

Similarly, several large exploits occurred in September and November 2023 on both DeFi and CeFi platforms: Mixin Network ($200 million), CoinEx ($43 million), Poloniex Exchange ($130 million), HTX ($113.3 million), and Kyber Network ($54.7 million).

Keep reading to learn more about crypto hacking trends in 2023, including how North Korea-affiliated cyber criminals had one of their most active years, executing more individual crypto hacks than ever before.

Attack vectors affecting DeFi are sophisticated and diverse

DeFi hacking exploded in 2021 and 2022, with attackers stealing approximately $2.5 billion and $3.1 billion, respectively, from protocols. Mar Gimenez-Aguilar, Lead Security Architect and Researcher at our partner Halborn, a security company specializing in web3 and blockchain solutions, told us more about the rise in DeFi hacking during those years. “There’s been a worrying trend in the escalation of both the frequency and severity of attacks within the DeFi ecosystem,” she explained. “In our comprehensive analysis of the top 50 DeFi hacks, we observed that EVM-based chains and Solana are among the most targeted chains, largely due to their popularity and capability to execute smart contracts.” When examining this trend last year, security experts told us that they believe many DeFi vulnerabilities stemmed from protocol operators focusing primarily on growth, and not enough on implementing and maintaining robust security systems.

However, for the first time since DeFi’s emergence as a key sector of the crypto economy, the yearly total stolen from DeFi protocols fell — and fell significantly.

The value lost in DeFi hacks declined by 63.7% year-over-year in 2023, and median loss per DeFi hack dropped by 7.4%. And, while the number of individual crypto hacks rose in 2023, the number of DeFi hacks specifically declined by 17.2%.

In order to understand this trend better, we worked with Halborn to analyze 2023 DeFi hacking activity through the lens of the specific attack vectors hackers utilized.

Classifying and analyzing attack vectors within the DeFi landscape

Attack vectors affecting DeFi are diverse and constantly evolving; it is therefore important to classify them to understand how hacks occur and how protocols might be able to reduce their likelihood in the future. According to Halborn, DeFi attack vectors can be placed into one of two categories: vectors originating on-chain and vectors originating off-chain.

On-chain attack vectors stem not from vulnerabilities inherent to blockchains themselves, but rather from vulnerabilities in the on-chain components of a DeFi protocol, such as their smart contracts. These aren’t a point of concern for centralized services, as centralized services don’t function as decentralized apps with publicly visible code the way DeFi protocols do. Off-chain attack vectors stem from vulnerabilities outside of the blockchain — one example could be the off-chain storage of private keys in, say, a faulty cloud storage solution — and therefore apply to both DeFi protocols and centralized services.

| Hack attack vector sub-category | Definition | On-chain or off-chain |

| Protocol exploitation | When an attacker exploits vulnerabilities in a blockchain component of a protocol, such as ones pertaining to validator nodes, the protocol’s virtual machine, or in the mining layer. | On-chain |

| Insider attack | When an attacker working inside a protocol, such as a rogue developer, uses privileged keys or other private information to directly steal funds. | Off-chain |

| Phishing | When an attacker tricks users into signing permissions, often done by supplanting a legitimate protocol, allowing the attacker to spend tokens on users’ behalf. Phishing may also happen when an attacker tricks users into directly sending funds to malicious smart contracts. | Off-chain |

| Contagion | When an attacker exploits a protocol due to vulnerabilities created by a hack in another protocol. Contagion also includes hacks that are closely related to hacks in other protocols. | On-chain |

| Compromised server | When an attacker compromises a server that is owned by a protocol, thereby disrupting the protocol’s normal workflow or gaining knowledge to further exploit the protocol in the future. | Off-chain |

| Wallet hack | When an attacker exploits a protocol that provides custodial/ wallet services and subsequently acquires information about the wallets’ operation. | Off-chain |

| Price manipulation hack | When an attacker exploits a smart contract vulnerability or utilizes a flawed oracle that does not reflect accurate asset prices, facilitating the manipulation of a digital token’s price. | On-chain |

| Smart contract exploitation | When an attacker exploits a vulnerability in a smart contract code, which typically grants direct access to various control mechanisms of a protocol and token transfers. | On-chain |

| Compromised private key | When an attacker acquires access to a user’s private key, which can occur through a leak or a failure in off-chain software, for example. | Off-chain |

| Governance attacks | When an attacker manipulates a blockchain project with a decentralized governance structure by gaining enough influence or voting rights to enact a malicious proposal. | On-chain |

| Third-party compromised | When an attacker gains access to an off-chain third-party program that a protocol uses, which provides information that can later be used for an exploit. | Off-chain |

| Other | Either the attack does not fit in any of the previous categories or there is not enough information to properly classify it. | On-chain/ off-chain |

Source: Halborn

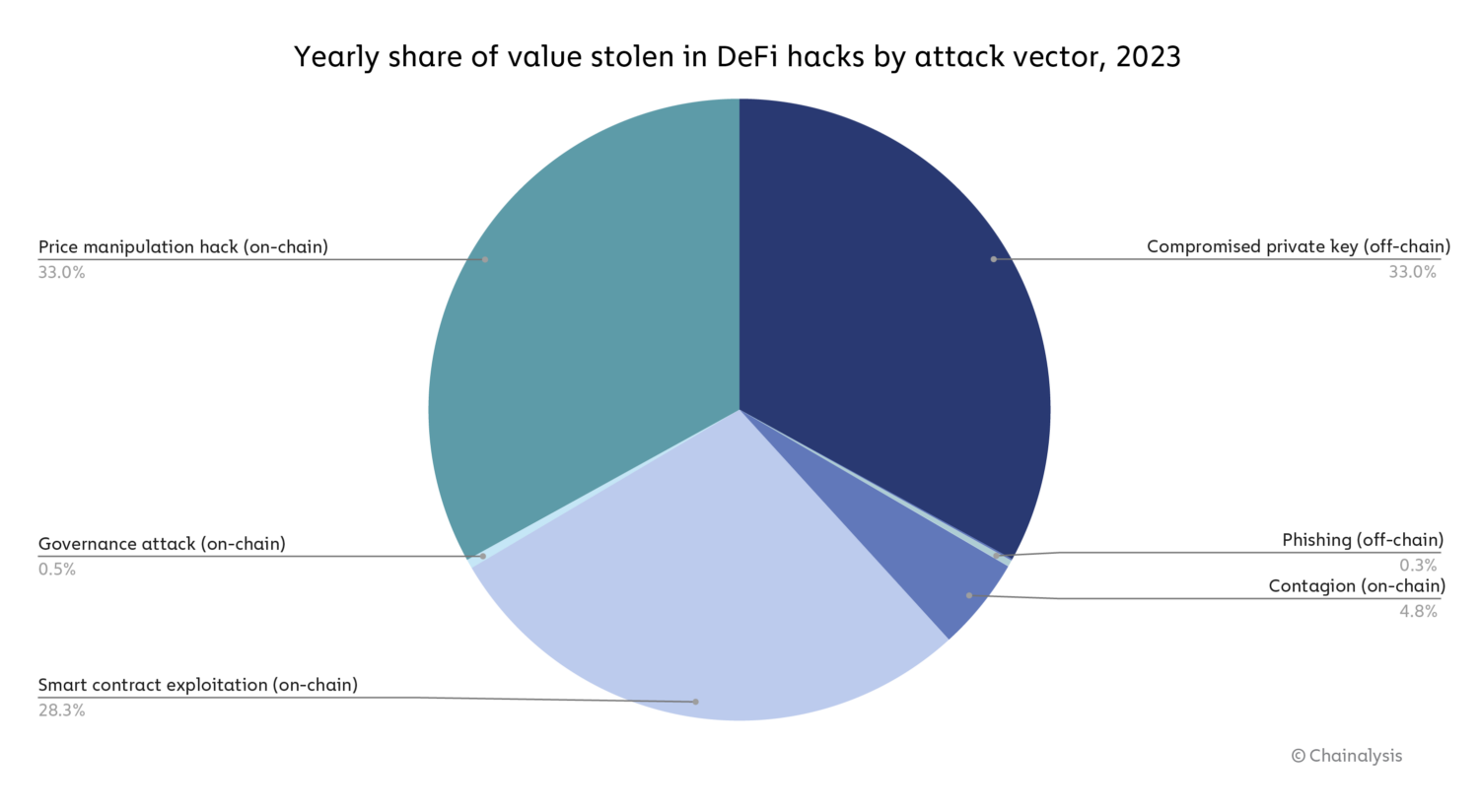

According to Gimenez-Aguilar, both on-chain and off-chain vulnerabilities present serious concerns. “Historically, the majority of DeFi hacks have stemmed from vulnerabilities in smart contract design and implementation — a large proportion of the affected contracts we examined had either not undergone any audit or had been audited inadequately,” she said, explaining on-chain vulnerabilities. “Another notable trend is the increase in attacks as a result of compromised private keys, which underscores the importance of improvements in security practices outside of a given blockchain.”

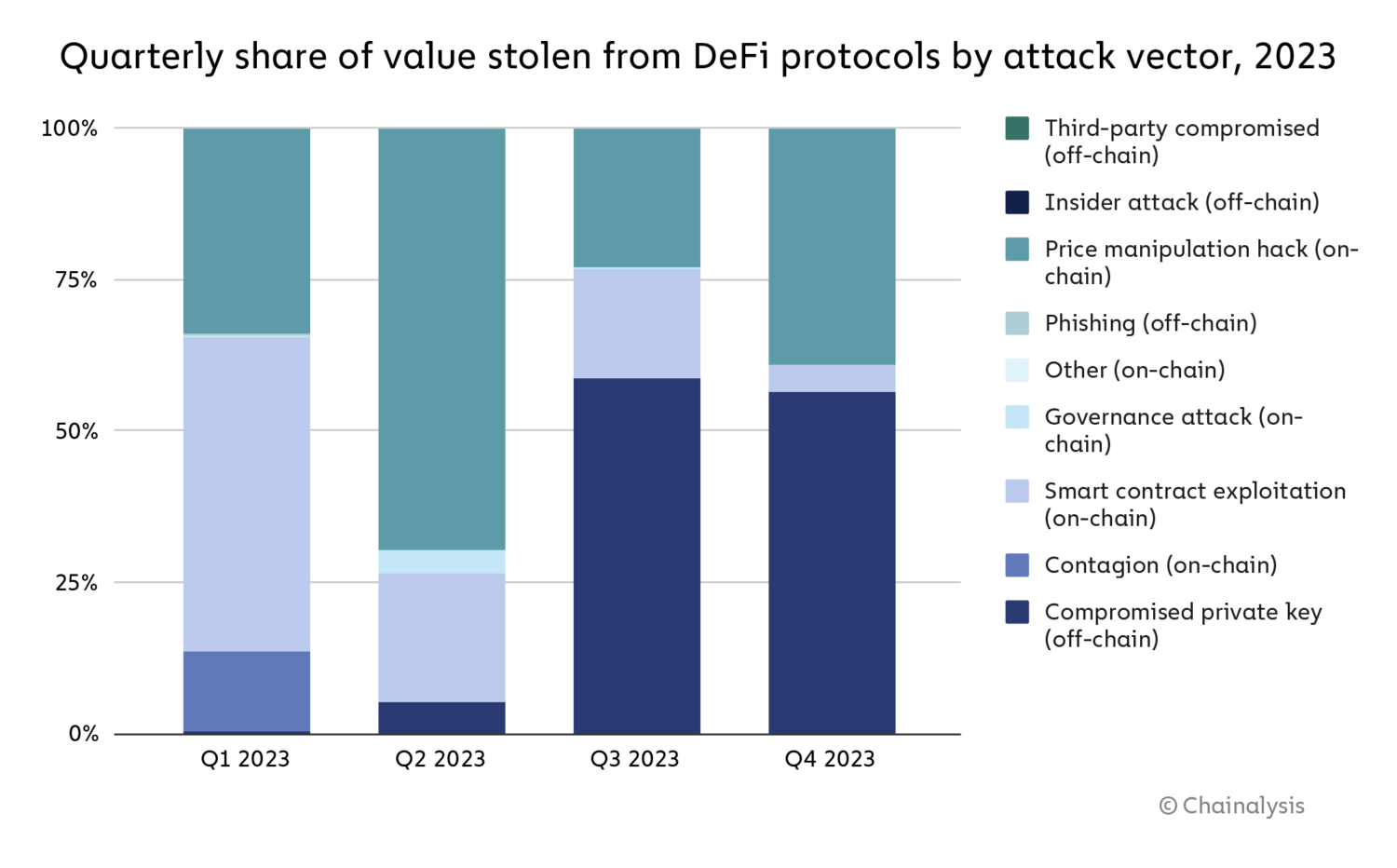

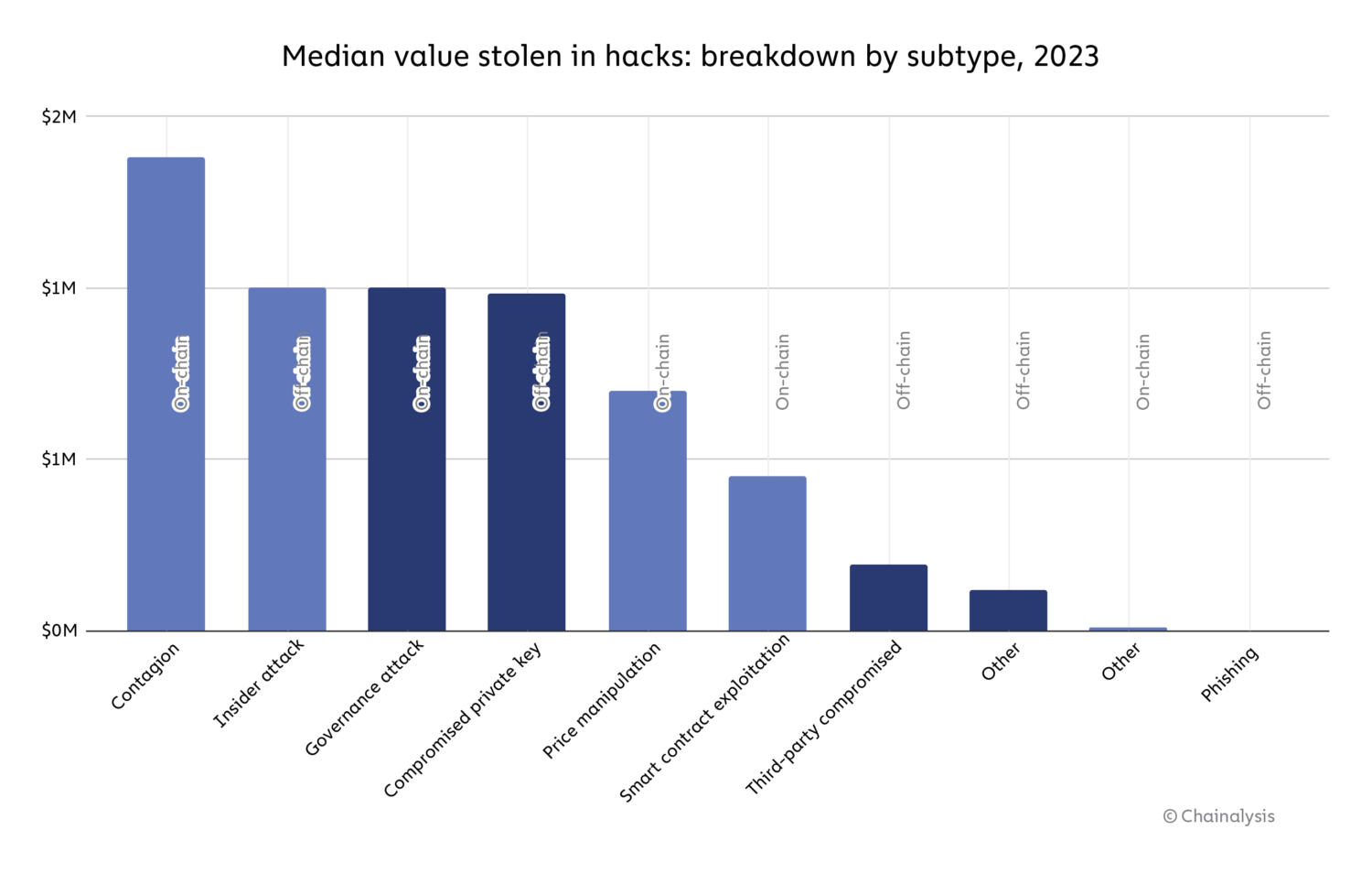

Indeed, the data shows that both the on-chain and off-chain vulnerabilities Gimenez-Aguilar describes — in particular the compromise of private keys, price manipulation hacks, and smart contract exploitation — drove hacking losses in 2023.

Source: Halborn

Overall, on-chain vulnerabilities drove the majority of DeFi hacking activity in 2023, but as we see on the chart below, that changed over the course of the year, with compromised private keys driving a larger share of hacks in the third and fourth quarters.

Source: Halborn

On a hack-by-hack basis, hacks stemming from contagion (on-chain) were the most destructive, with a median loss of $1.4 million. Governance attacks (on-chain), insider attacks (off-chain), and compromised private keys (off-chain) follow, with all three accounting for a median hack value of roughly $1 million.

Source: Halborn

Overall though, the data provides reasons for optimism. Both the drop in raw value stolen from DeFi, and the relative decline in on-chain vulnerability-driven hacking over the course of 2023 suggests that DeFi operators may be getting better at smart contract security. “I do think that the increase of security measures in DeFi protocols is a key factor in the reduction in the quantity of hacks related to smart contracts vulnerabilities. If we compare the top 50 hacks by value lost from this year with those from previous ones (studied in Halborn’s Top 50 hacks report), there is a reduction in percentage of losses from 47.0% of the total to 18.2%. Price manipulation attacks, nevertheless, remain almost constant with around 20.0% of the total value lost. This is an indication that, when performing an audit, protocols should also take into account how they interact with the whole DeFi ecosystem,” said Gimenez-Aguilar. However, she also stressed that the growth in hacks driven by attack vectors such as compromised private keys indicates that DeFi operators must move beyond smart contract security and address off-chain vulnerabilities as well: “Doing the same comparison as before, losses related to compromised private keys increased from 22.0% to 47.8%.” As we see above, both on-chain and off-chain vulnerabilities can be highly destructive.

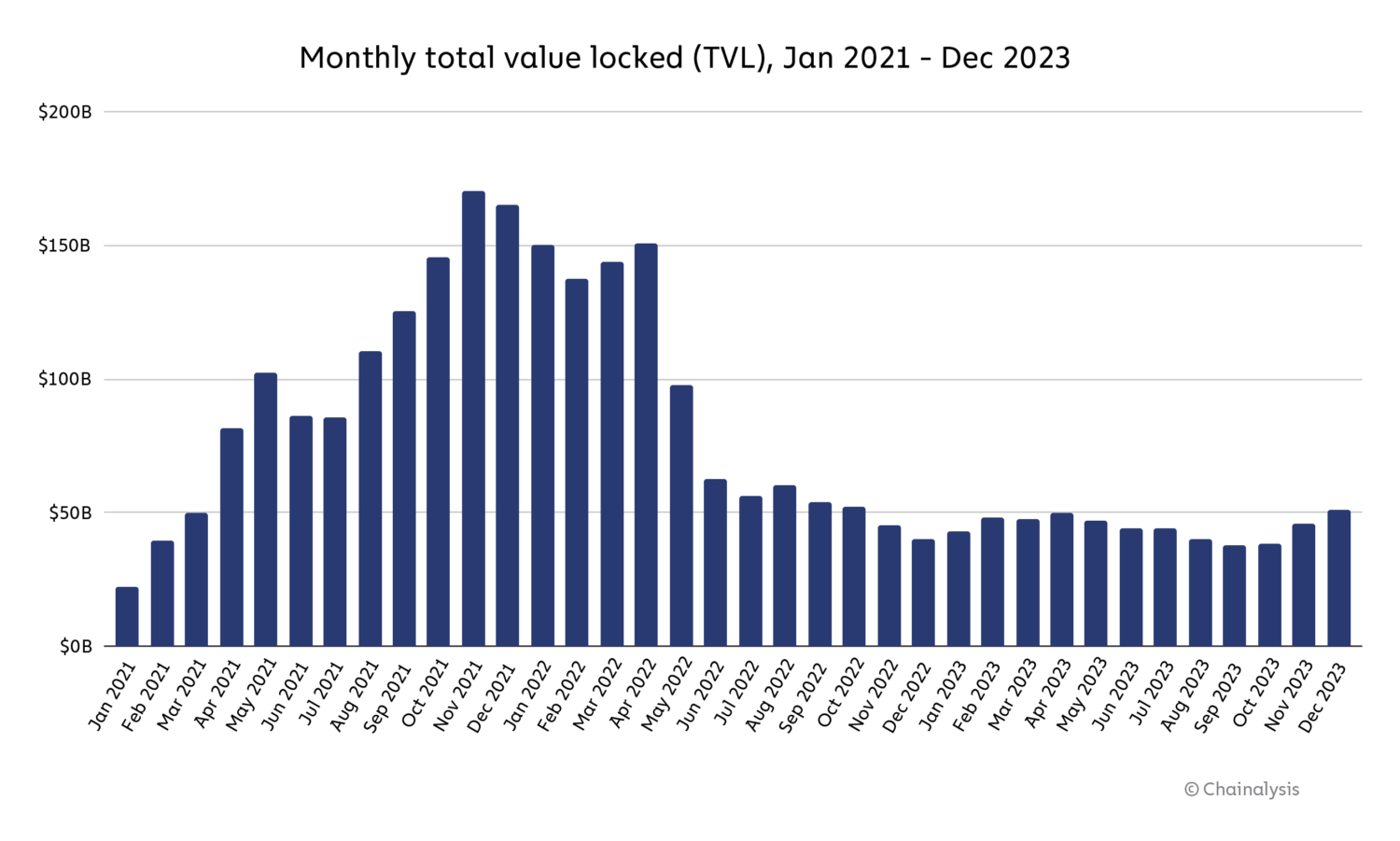

However, Gimenez-Aguilar also acknowledged that the drop in DeFi hacking losses may be driven in part by the overall drop in DeFi activity in 2023, which may have simply decreased the number of DeFi protocols that made ripe targets for hackers. Total value locked (TVL), which measures the total value held or staked in DeFi protocols, was down for all of 2023, following a sharp decrease in the middle of 2022.

Source: DeFiLlama

We can’t say for sure whether the drop in DeFi hacking was driven primarily by better security practices or the drop in DeFi activity overall — most likely, it was a mix of the two. But, if the decrease in hacking was primarily driven by the drop in overall activity, then it would be important to watch whether DeFi hacking rises again in tandem with another DeFi bull market, as this would lead to higher TVL and therefore a larger pool of DeFi funds for hackers to target.

Regardless, there are steps DeFi operators should take to improve security. DeFi protocols vulnerable to on-chain failures can develop systems that monitor on-chain activity related to economic risks and prior platform losses. Companies such as Hypernative and Hexagate, for example, produce customized alerts to prevent and react to cyber attacks, which can help platforms better secure integrations with third parties such as bridges, and communicate with customers who might be at risk. Platforms vulnerable to off-chain failures may aim to reduce reliance on centralized products and services.

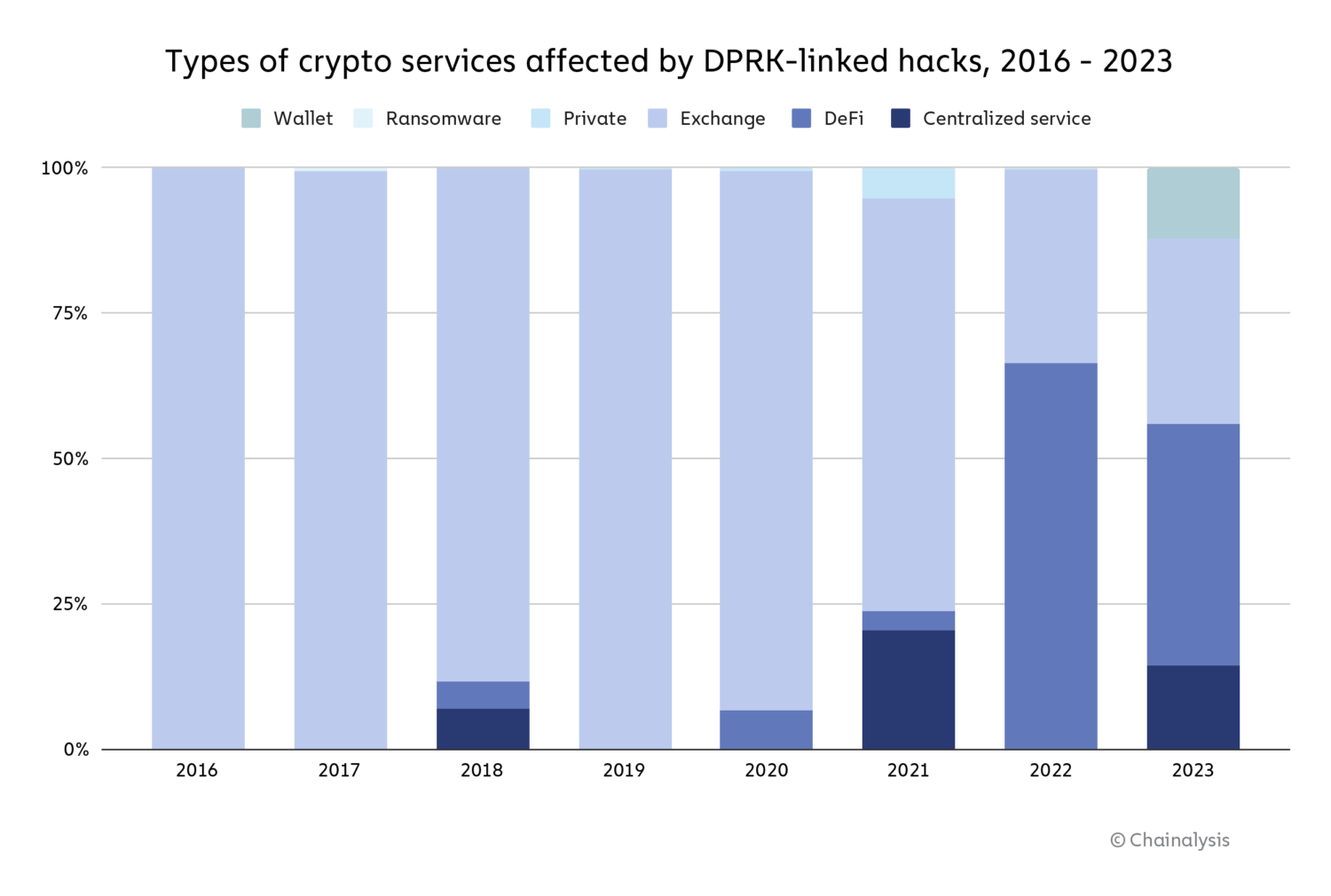

North Korea hacked more crypto platforms than ever in 2023, but stole less in total than in 2022

North Korea-linked hacks have been on the rise over the past few years, with cyber-espionage groups such as Kimsuky and Lazarus Group utilizing various malicious tactics to acquire large amounts of crypto assets. In 2022, cryptocurrency stolen by hackers associated with North Korea reached its highest level of approximately $1.7 billion. In 2023, we estimate that the total amount stolen is slightly over $1.0 billion, but as we see below, the number of hacks rose to 20 — the highest number on record.

We estimate that North Korea-linked hackers stole approximately $428.8 million from DeFi platforms in 2023, and also targeted centralized services ($150.0 million stolen), exchanges ($330.9 million), and wallet providers ($127.0 million).

2023 saw a notable decrease in North Korean targeting of DeFi protocols, mirroring the overall drop in DeFi hacking that we discussed above.

Case study: The DPRK’s Atomic Wallet exploit

In June 2023, thousands of users of Atomic Wallet, a non-custodial cryptocurrency wallet service, were targeted by a hacker, leading to estimated losses of $129 million. The FBI later attributed this attack to North Korea-affiliated hacking group TraderTraitor and stated that the Atomic Wallet exploit was the first in a series of similar attacks, including the Alphapo and Coinspaid exploits later in the month. Although the specifics of how the attack occurred remain unclear, we used on-chain analysis to look at what happened to the funds after the initial attack, which we’ve broken down into four phases.

In the first phase, the attacker chain hopped — moving assets from one blockchain to another, typically to obfuscate the flow of ill-gotten funds — to the Bitcoin blockchain via the following three methods:

- Sending funds to centralized exchanges. While we can’t continue to trace funds on-chain following their movement to a centralized service, we know in this case that funds stolen from Atomic Wallet were converted into Bitcoin at centralized exchanges because we gathered intelligence from other trusted sources with whom we regularly collaborate.

- Sending funds to cross-chain bridges where they could be moved to the Bitcoin blockchain.

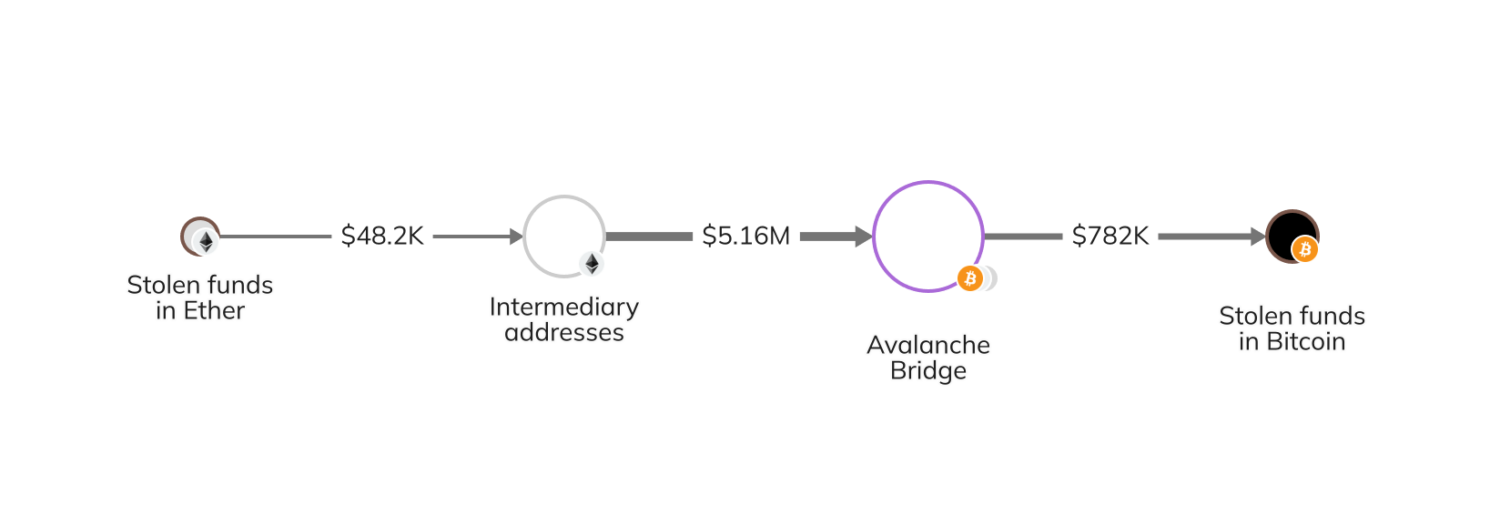

- Sending funds to wrapped Ether (wETH) contracts, then moving to the Bitcoin blockchain via the Avalanche Bridge.

The Chainalysis Reactor graph below illustrates the third method whereby the stolen funds (in Ether at the time) moved through several intermediary addresses before reaching the Avalanche Bridge and converting to Bitcoin.

In the second phase, the attacker sent the stolen funds to the OFAC-sanctioned Sinbad, a mixing service that obscures on-chain transaction details and has been previously used by North Korean money launderers. Then, the attacker withdrew the funds from Sinbad and moved them to consolidation addresses on Bitcoin.

In the third phase, the attacker’s money laundering strategy shifted to focusing almost exclusively on the Tron blockchain rather than the Bitcoin blockchain. The attacker chain hopped to the Tron blockchain via one of the following methods:

- Sending funds to Avalanche through the Avalanche Bridge where they could be moved to the Tron blockchain.

- Sending funds to centralized services, then moving them to the Tron blockchain.

- Sending funds through additional mixers or privacy-enhancing services to further obfuscate the flow of funds, then moving them to the Tron blockchain.

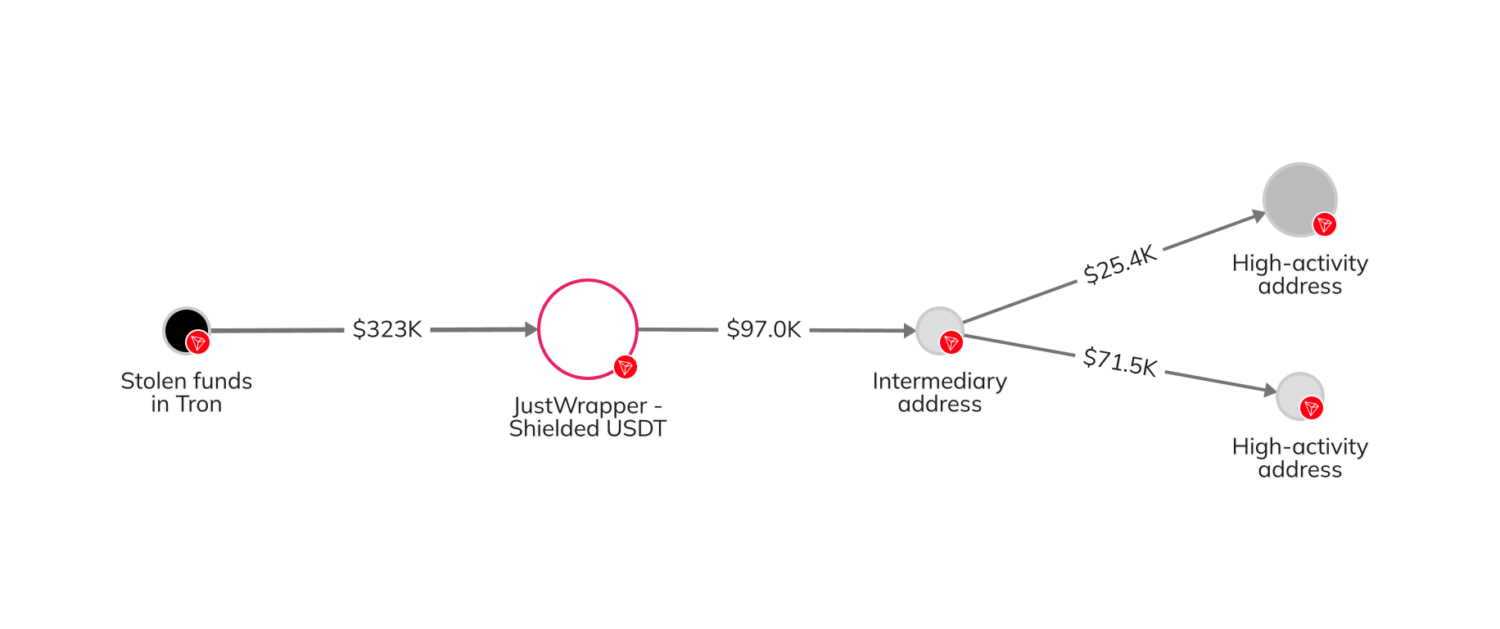

In the fourth and final phase, the attacker deposited the funds at various services on the Tron blockchain. Some of these funds were mixed via Tron’s JustWrapper Shielded Pool, whereas others were ultimately sent to high-activity Tron addresses suspected of belonging to over-the-counter traders.

Additional on-chain activity revealed that funds stolen from Atomic were consolidated with assets from other sources before moving elsewhere, which is likely related to the subsequent Alphapo and Coinspaid exploits.

The future of crypto hacking

Although the total amount stolen from crypto platforms in 2023 was down significantly from prior years, it is clear that attackers are becoming increasingly sophisticated and diverse in their exploits. The good news is, crypto platforms are becoming more sophisticated in their security and responses to attacks, too.

When crypto platforms act promptly after exploits, law enforcement agencies will be better equipped to contact exchanges where frozen funds are located to initiate seizure and contact services through which the funds flowed to gather relevant information about accounts and users. Over time, as these processes improve, it is likely that funds stolen from crypto hacks will continue to decline.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, investment, regulatory or other professional advice, nor is it to be relied upon as a professional opinion. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information herein. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.