While there are trillions of microbes in the gut microbiota, they are easily affected when exposed to various environmental influences. These are reflected in the behavior of one microbe, Lactobacillus (LB), in response to mood pathology and stressors. A new study in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity extends these findings in a mouse model, showing that this organism protects against such disruption via its ability to maintain the levels of an important cytokine, interferon-gamma (IFNγ), at physiologically normal levels.

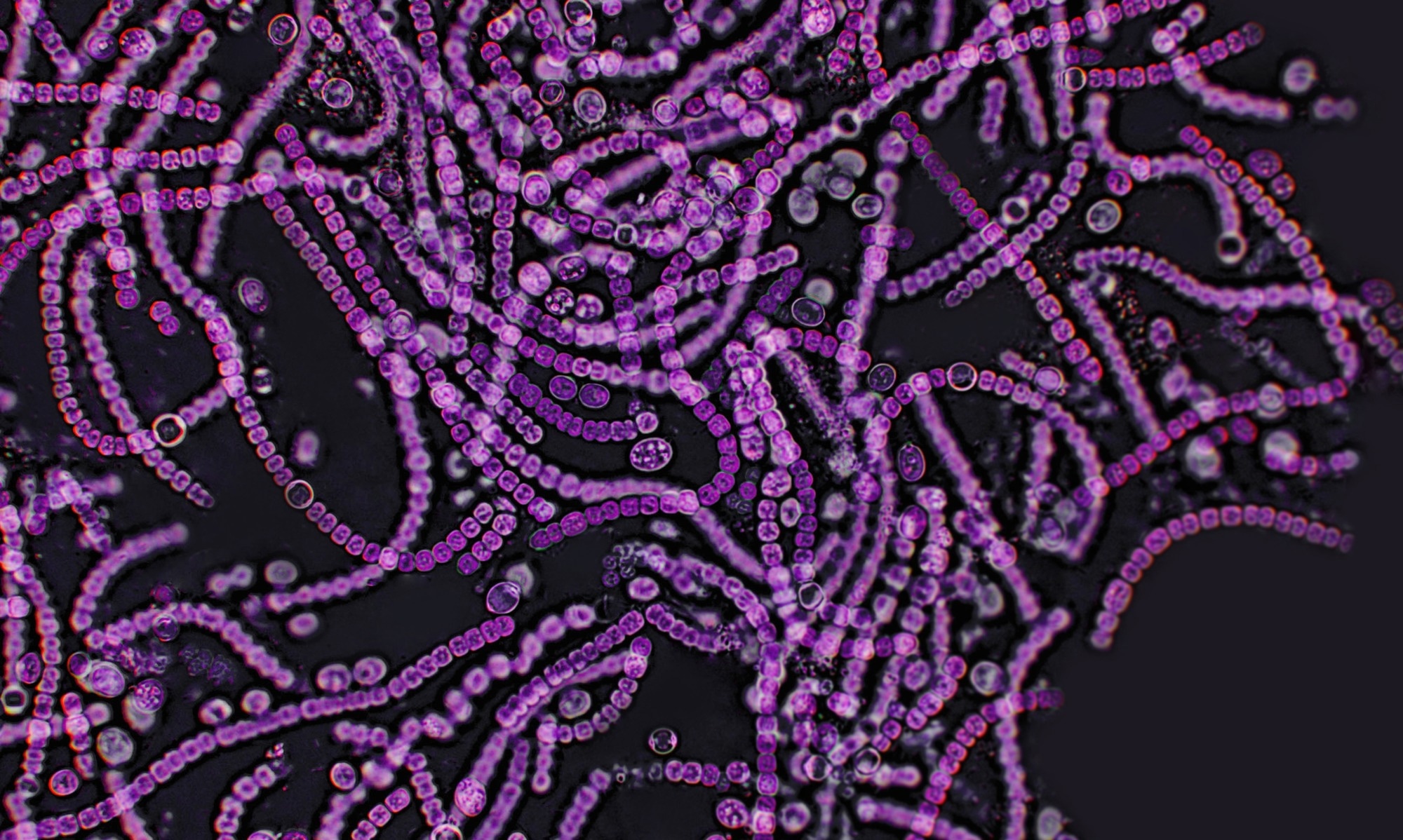

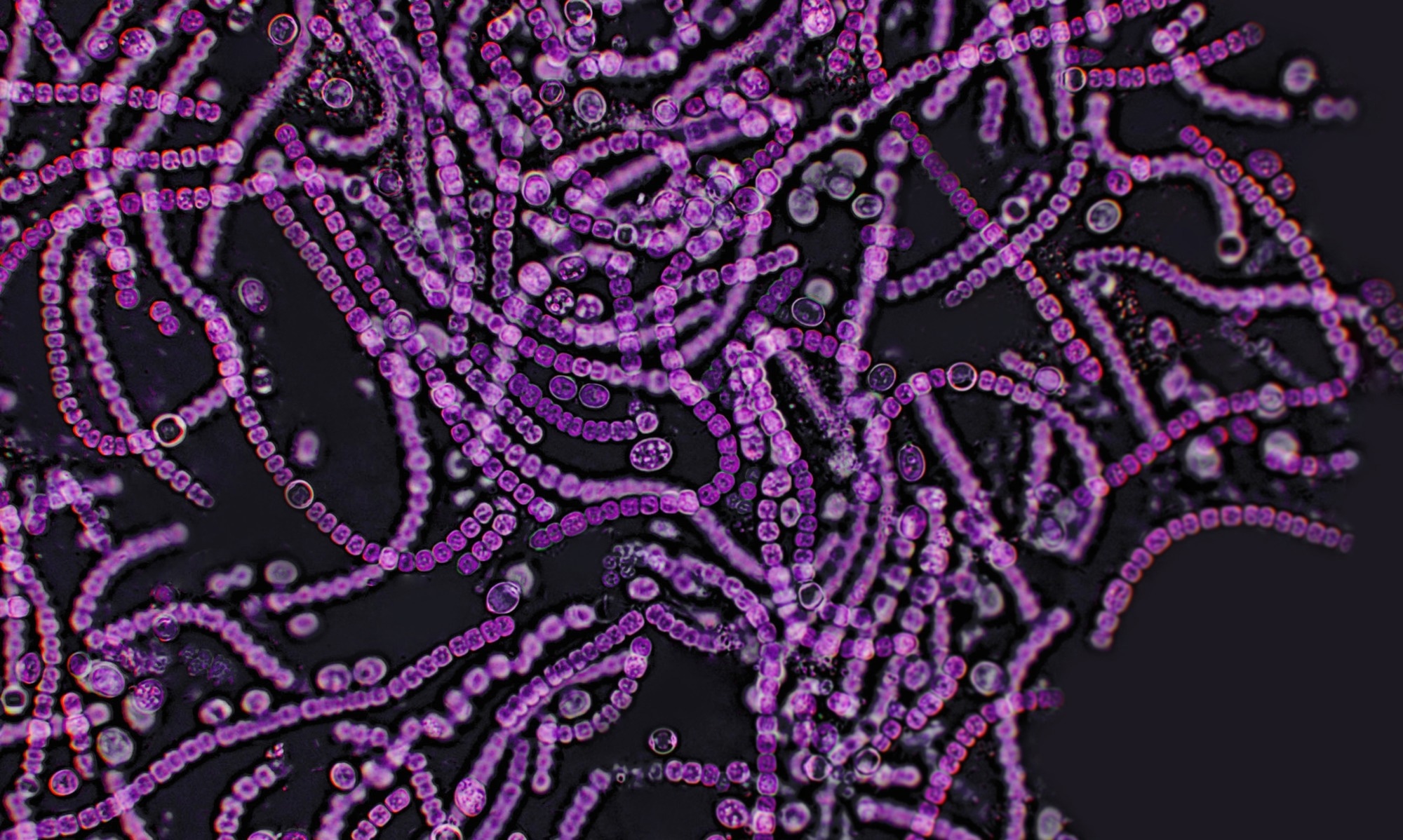

Study: Lactobacillus from the Altered Schaedler Flora maintain IFNγ homeostasis to promote behavioral stress resilience. Image Credit: Elif Bayraktar / Shutterstock

Study: Lactobacillus from the Altered Schaedler Flora maintain IFNγ homeostasis to promote behavioral stress resilience. Image Credit: Elif Bayraktar / Shutterstock

Earlier research showed a close connection between the gut microbiota and the brain, spurring new studies into the effect of perturbations in the former on mental health. Dysbiosis has often been identified in patients under stress or with mood disorders, especially with respect to LB. Moreover, in both human and animal studies, this organism has been found to improve the individual’s mood and relieve anxiety while enhancing resistance to stress.

This so-called “psychobiotic” effect has been noted across various species and strains of LB, indicating that the organisms themselves are responsible for the observed benefit. However, certain findings suggest that some species, such as L. intestinalis and L. reuteri have detrimental effects on the host. Little is known about what would happen if LB were to be completely removed.

The Altered Schaedler Flora (ASF) refers to a gnotobiotic consortium or set of bacteria in which all members are well-known. Established in 1978, ASF includes 8 bacterial strains that have been vertically transmitted. It includes two LB strains, which were removed in the current study, thus producing some mice lacking LB from birth (ASF(-L) vs the other ASF(+L) mice that received the whole ASF consortium.

The researchers aimed at understanding how these bacteria affected behavior, immune development, and mood.

What did the study show?

The study suggests that stress resistance is developed through type 1 adaptive immune pathways. This involves the ability of LB to maintain homeostatic levels of IFNγ. Overall, the researchers conclude that both LB and IFNγ are required to build resilience into an organism when exposed to environmental stressors.

One set of mice was exposed to two hours of restraint daily at unpredictable times. In addition, one other stressor was used: damp bedding, a tilted cage, or being forced to shift cages twice within 24 hours. These exposures continued for three weeks, after which their behavioral responses to chronic restraint stress were tested.

For two weeks, dirty bedding from the cages of these mice was put into the cages of female GF mice. This second set of mice was then left as such for another two weeks before being tested.

Anti-IFNγ injections were administered to the mice 14 hours before being exposed to acute stress and IFNγ 5 minutes before. IgG2A (immunoglobulin G2A) was given to a control group. One subgroup of the controls was not exposed to stress.

A fourth group of mice were ASF mice. They were exposed to mild acute stress in the form of restraint in 50 mL conical vials out of their cages for 3 hours, vs. subclinical stress where another group was restrained for two hours daily for seven days in their cages, at different times of the day. These were tested for stress and then sacrificed for testing.

Chronic mild random stress results in the first group of mice included more repetitive behavior like nestlet shredding and less active time in the tail suspension test. They also showed lower LB levels and dysbiosis, with no compensatory rise in any other bacterial species.

Interestingly, the transfer of the bedding contaminated by these chronically stressed mice to germ-free (GF) mice showed that the gut microbiota transferred to the new host-induced behaviors resembling that associated with anxiety and depression by itself. With other studies, this finding suggests that “the microbiota can directly modulate behavior.”

Metabolomics studies showed that animals exposed to the bedding of the stressed animals had a lower profile of adaptive immunity associated with Type 1 helper T (Th1) cells. They also had lower systemic levels of IFNγ, a key molecule in adaptive immunity and a central molecule in gut-brain communication. It has recently been found to be associated with sociability via its direct action on neurons.

This was in addition to higher cortisol levels and changes in several metabolic pathways. Many of these chemicals were linked to mood, such as thyroxine or T4, and lenticin, an indol compound. Further exploration showed that meningeal transcription of IFNγ was reduced.

Overall, exposure to gut microbiota from stressed animals resulted in lower type 1 immune markers, particularly IFNγ.

Both ASF(+L) and ASF(-L) had comparable proportions and numbers of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, as well as monocytes and B cells. However, the transcriptional marker, Tbet, for IFNγ in small intestinal cells was reduced in ASF(-L) mice. They also had a lower proportion of activated CD4+ cells bearing Tbet and the activation/memory marker CD69.

Moreover, mice lacking LB were more prone to develop stress after restraint and showed lower numbers of Type 1 helper T cells (Th1 cells). Neuronal activation was higher in stressed ASF(-L) mice than in ASF(+L) mice.

This suggests that LB is “a novel regulator of Tbet expression and perhaps Type 1 immune responses.”

The researchers observed that ASF(-L) mice showed anxiety- and depression-like behaviors when exposed to subclinical stress. The absence of LB appears to be linked to increased susceptibility to stress.

ASF(-L) mice had lower serum IFNγ than ASF(+L) mice. Only ASF(+L) mice showed a reduction in IFNγ after stress, suggesting that this may mediate psychological resilience when faced with environmental stressors. Since ASF(-L) mice do not have sufficiently high levels of IFNγ, their capacity to be resilient is low.

Animals injected with IFNγ showed muted responses to acute stress compared to those given anti-IFNγ antibodies, indicating that systemic IFNγ may increase one’s resistance to stress. Thus, circulating IFNγ is produced when LB is present in the gut, and both are required for resilience when faced with environmental stress. The IFNγ regulates stress-related behaviors.

What are the implications?

This study avoids using GF mice or mice treated with antibiotics before colonizing with specified bacteria to identify the effects of variations in the gut microbiota on mood disorders. This novel approach exploits the advantages of ASF, “a next-generation tool to study the microbiome.” These include normal development and reproduction as well as immunology, unlike GF mice, and antibiotic-related off-target effects as well as a higher presence of undesirable antibiotic-resistant organisms.

Further work is necessary to understand how metabolic and hormonal responses in stress interact bidirectionally with the gut microbiome to establish negative behavioral responses. ASF could be very useful in elucidating how specific probiotics affect the gut without having to adjust for other LB or unrelated species.

The results support the crucial role of IFNγ in stress-related behaviors, though the mechanisms remain unclear. The scientists have shown how it works to develop psychological resilience, and this work could promote the discovery of effective probiotics to help treat mood disorders.