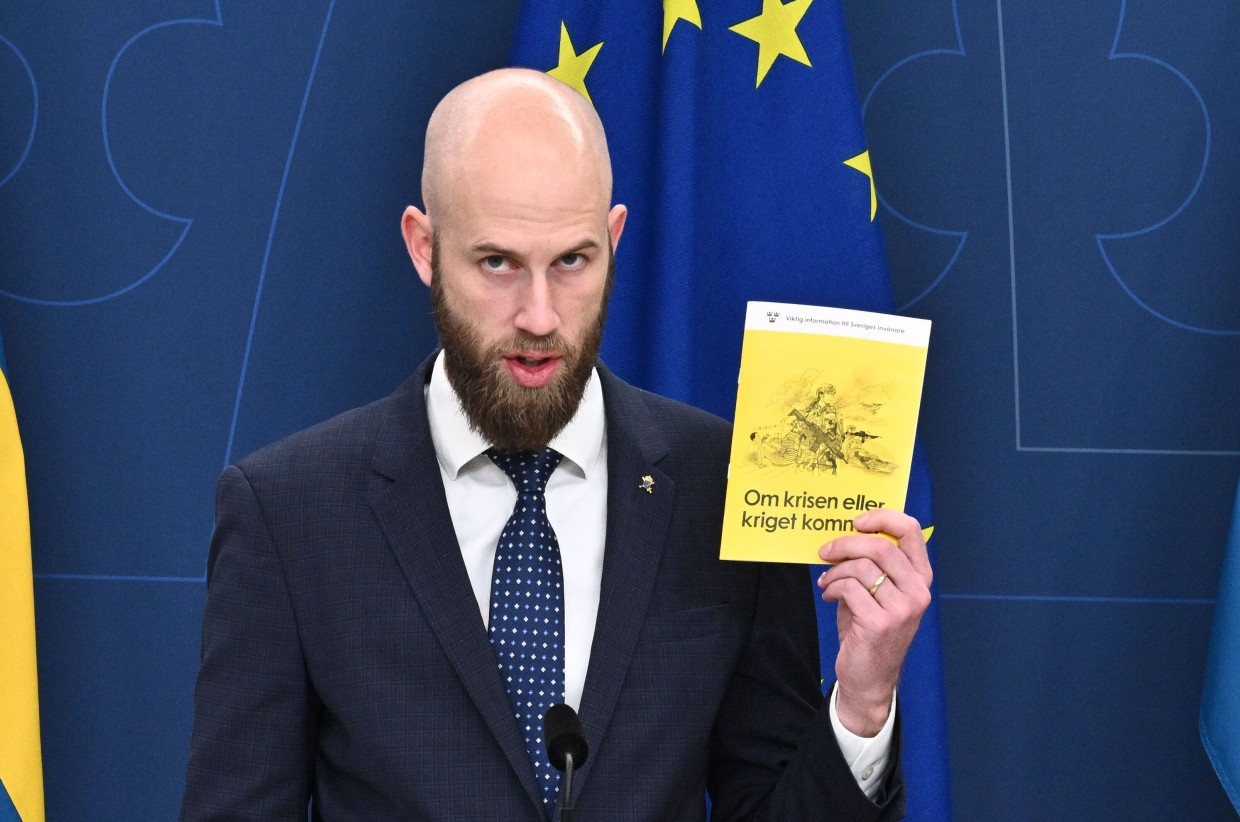

In Schweden erhält jeder Haushalt in diesen Tagen per Post ein kleines gelbes Heftchen. Die Vorderseite ist sehr schwedisch gestaltet, im Mittelpunkt stehen starke Frauen. Eine große Soldatin mit Gewehr schützt eine Frau mit Kindern dahinter, rechts daneben ist ein kleiner männlicher Soldat zu sehen, dazu ein Kriegsschiff sowie ein Kampfflugzeug. „Wenn eine Krise oder ein Krieg kommt“, steht darunter. Auf 32 Seiten folgen Hinweise.

Etwa dazu, wie man sich im Kriegsfall oder bei Terrorangriffen verhält; welche Vorräte anzulegen sind, um für eine Woche ohne Unterstützung auszukommen; wo man Schutz findet und wie Desinformation zu erkennen ist. „Wenn Schweden angegriffen wird, werden wir uns niemals ergeben. Alle Angaben, dass der Widerstand aufhören wird, sind falsch“, steht ganz zu Beginn.

Solche Broschüren gab es in Schweden schon früher, das letzte Mal vor sechs Jahren. Die aktuelle Ausgabe ist umfangreicher geworden, die Zeiten sind schwieriger. Ein ähnliches Schreiben erhielten kürzlich die Menschen in Norwegen. Auch von der dänischen Agentur für Notfallmanagement gibt es vergleichbare Broschüren, und in Finnland, gewissermaßen Weltmarktführer in Sachen Krisenbereitschaft, wurden kürzlich die Empfehlungen an die Bevölkerung für Krisenzeiten aktualisiert. Das zeigt: Zivilschutz wird in den nordischen Ländern ernst genommen. Dieser soll – neben dem kräftigen Ausbau der militärischen Fähigkeiten – einen wichtigen Beitrag zur Verteidigung leisten.

Dieser Text stammt aus der Frankfurter Allgemeinen Sonntagszeitung.

This is a turning point for Sweden, but unlike in Germany, it is being implemented pragmatically and quickly. Both countries are similar in their history of defense preparedness. During the course of the Cold War, Sweden massively expanded its military capabilities and invested heavily in civil defense. The aim was a defense policy that included the military and the population. This was called total defense. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, it seemed superfluous, the armed forces were converted into small, powerful specialists, military service was abolished, and civil defense was neglected.

Marika Ericson is a lawyer at the Swedish Defense University in Stockholm and researches the topic of crisis preparedness. She says that in Sweden it has been assumed since the 1990s that there would be no more war. The overall defense system was fragmented; municipalities were now primarily responsible for civil protection. This continued until 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea. “Then reality came back,” she says.

Military service since 2018

Even then, Sweden flipped the switch, much earlier than Germany. Military service was reintroduced in 2018. Since the beginning of the Russian war of aggression, efforts have been significantly increased. Massive investments are being made in the armed forces and civil defense is also being rebuilt. All of this takes time. According to the responsible authority, there are still around 65,000 shelters for the approximately 10.5 million Swedes, recognizable by a sign with an orange square and a blue triangle in it. However, over the years many have been built up or converted into bicycle storage rooms.

Ericson says the state of the overall defense is far from perfect and there is a lot of work to be done. The old laws for emergencies were never abolished, and the Swedes can now build on them. A lot of things have to be adapted, for example in the digital area. “But we have an institutional memory to build on,” Ericson says.

In the spring, Swedish politicians and military officials frightened their own population. “There could be war in Sweden,” that must be said with “unvarnished clarity,” said Civil Protection Minister Carl-Oskar Bohlin. That generated a lot of attention. Some in the country found the warning exaggerated. And researcher Ericson is not sure whether the policy has really reached everyone.

The gold standard of crisis preparedness

Things are different in Finland. A recent survey there caused a stir, according to which around forty percent of the population do not have sufficient reserves at home to survive a prolonged crisis. Conversely, this means: Sixty percent of households have sufficient supplies. In other countries one would be very proud of this number. But not in the extreme north-east of Europe.

The experience of being invaded by the Soviet Union during the Second World War and left to fend for oneself is deeply etched here. At that time, the military recognized that the help of the population was absolutely necessary in order for a small nation to be able to survive on its own in the fight against its large neighbor.

Even after the end of the Soviet Union, the Finns did not trust the Russians. Military and social preparedness was never reduced. This is how Finnish conditions became the gold standard for crisis preparedness. In Helsinki alone there are shelters for around 900,000 people, although only around 650,000 live there. You also think about commuters.

Many of the protective structures are not even recognizable as such. Some serve as sports facilities, others as churches. The armed forces are large with around 280,000 soldiers who can be mobilized in the event of war, and there are a total of almost 900,000 reservists. And the population is very well prepared for all kinds of crises.

Aleksi Aho works at the European Center of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats in Helsinki. For him, military service is “the basis for the Finnish system of total defense.” Aho is a vulnerability and resilience analyst. Finland is the only Nordic country that has consistently maintained military service for all men. A large part of the population is trained to deal with threats and crises. The country's reservists receive regular training, and many civilians also attend military courses. There are courses for students over the age of 16, as well as for the elite from politics and business.

The Finns were therefore often ridiculed by their Nordic neighbors, especially the cosmopolitan Swedes, as a backward-looking prepper nation. That's over today. Groups of visitors now come regularly to learn. The EU now also wants to do this.

The EU should become more Finnish

But even in Finland there are opportunities for improvement. During the pandemic, it was discovered that all the masks that the responsible authority had stored in case of a crisis had expired. And now that the country, like Sweden, is a NATO member, it must rethink its perception of itself as a lone nation fighting Russia. After all, the obligation to provide assistance applies in the event of war.

Despite NATO, the Nordic countries still feel at risk. Both in terms of a possible military attack by Russia and through hybrid attacks below the threshold of war. These have increased massively in the Baltic Sea region. The most recent example may be the recently destroyed data cables on the seabed. The incident surprised hardly anyone in Helsinki and Stockholm.