Ein video: Olga and her students dance flamenco in the dark, in the center of Kyiv, lit by just two candles. One sees little and can guess Olga’s movements through the abrupt beats of her steps. And now everyone together: groping and resolute at the same time, a new language of movement, of dignified living, is emerging. It’s magical, the darkness of war recedes for a moment.

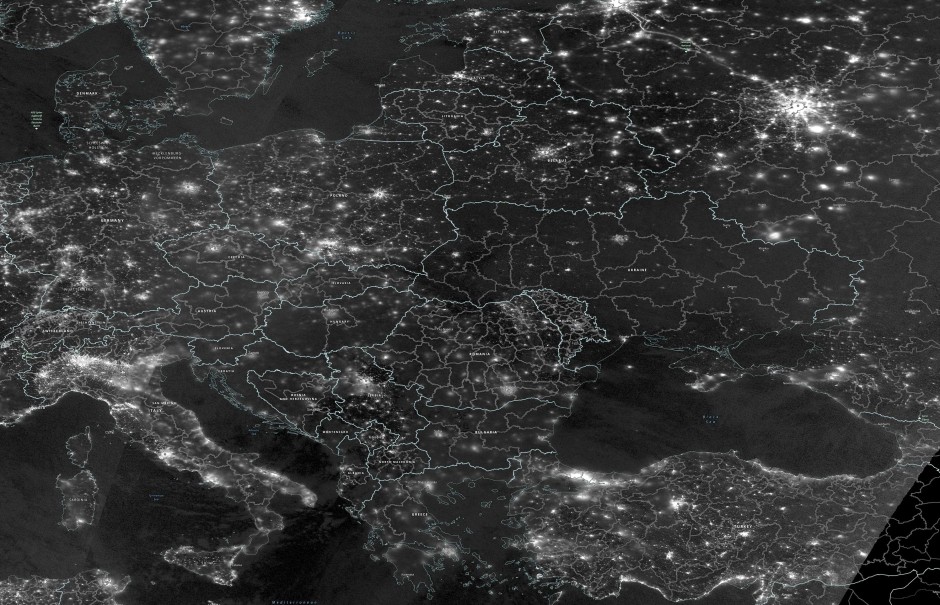

I see the NASA image and feel the light of Olga and the dancers in her dance studio. They are there somewhere. This image shows a complex drawing: darkness with craquelure of light, country borders, constellations of cities, reminding me of Malevich’s “Square”, which was supposed to prophesy the end of art: it has similar white cracks in the texture of the black surface – for your own salvation. I wanted to write about the darkness and how the people of Ukraine plunged into that darkness. I don’t want them to sink into her.

If I were a magic lawyer

Now the most difficult phase of the war begins for the population: power, water and heating failures in the coming cold months, in the darkest time. My friends in the big cities persevere, accept it in a disciplined manner, almost athletically, learning the complexities of everyday life in the face of power cuts.

But what about those who live in cities with completely destroyed infrastructure? What does that mean for the army, for an intensive care unit, for a maternity hospital? I would have preferred to write an appeal here, a list of citizens’ groups that buy generators that save lives. I think of this need. And if I were a magic lawyer, I would have turned Gerhard Schröder’s fortune into generators.

I have known Olga all my life. We used to sing together in the Shchedryk children’s choir, three times a week for ten years, in the October Palace above the Maidan. In 2014 she led me across the protest site, we even stood briefly on the barricades, and her husband Sascha, whom we all stubbornly called “Ostap”, then proudly showed me the cannon stoves that he built for the protesters’ tents so that nobody had to freeze .

Ostap was an engineer and a brilliant hobbyist. When the war first broke out, he was committed to modernizing the army, and I didn’t immediately understand his move. Almost exactly two years ago, shortly after my father died, he died of Covid after a long struggle. I thought at the time that we had reached the pinnacle of fateful unpredictability and sadness.

Opera in the air raid shelter

Olga is always a light for me in this war. I always call her. She tells me about her “professor’s backyard” where she lives and which has organized itself since the beginning of the war: when the supply in the city collapsed, the people from Olga’s farm collected aid supplies for the needy. They streamed opera performances in their air-raid shelter because a physicist who runs the Wagner Society lives there.

Olga was the first I heard about relatives dying, in the suburbs of Kiev. Recently, her Canadian sister, who was visiting the Himalayas as a tourist, came to visit with mountaineering gear, and the whole farm learned simple tricks to better endure the cold. A colourful, funny, tragic practice for life. The other day Olga told me how she bought USB lamps, daylight panels and even massage candles at the market – everything that glows.

My brother wrote to me today. He traveled to Lviv from Chicago to present a book on the city’s architectural history. He just wanted to go to Ukraine. He was wandering somewhere in the dark with a flashlight: the NASA image on a human scale – he wanted to call me, but only wrote briefly from beautiful Lemberg: “Power failure, air raid alarm, I’ll be in touch soon.” And I’m waiting.