Jan. 6, 2023 – Even if the causes of long COVID remain confusing, researchers are zeroing in on biomarkers – compounds that can be detected and measured – that can help them better diagnose and treat the condition. The eventual goal: a simple test to help determine who has long COVID and whether treatments are helping.

“The hope is that the specific markers that are discovered will inform how individual clusters (of disease) should be treated and managed to either reduce or eliminate symptoms,” says David Walt, PhD, co-director of the Mass General Brigham Center for COVID Innovation in Boston.

Biomarkers are commonly used to identify and track diseases. They range from simple measurements such as blood pressure or blood glucose levels to the autoantibodies that cause rheumatoid arthritis and the enzymes that can indicate liver disease. As long COVID’S maddening range of symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, and dizziness, having a biomarker or several biomarkers could help better define and diagnose it.

Michael Peluso, MD, who has been treating COVID-19 and long COVID patients at San Francisco General Hospital since the beginning of the pandemic, says a “game changer” biomarker would be “finding something where you can do an intervention today, see a change in the level of the marker, and know that it will have a long-term impact.”

Researchers know that patients should not expect a single diagnostic test or research metric to emerge. Several things appear to be linked to various symptoms. Scientists and doctors predict they will establish different clinical subtypes of long COVID.

Many research teams are working under the umbrella of the RECOVER Initiative, a $1.15 billion National Institutes of Health long COVID project. The NIH has funded 40 research projects looking at the role of metabolism, genetics, obesity, antibodies, inflammation, diabetes, and more.

The NIH team has divided long COVID into symptom clusters and is looking for what drives illness in each cluster. The clusters are:

- Viral persistence: When the COVID-19 virus stays in some people’s bodies

- Autonomic dysfunction: Changes in ability to regulate heart rate, body temperature, breathing, digestion, and sensation

- Sleep disturbances: Changes to sleep patterns or ability to sleep

- Cognitive dysfunction: Trouble thinking clearly or brain fog

- Exercise intolerance/fatigue: Changes in a person’s activity and/or energy level

The RECOVER studies are expected to begin in early 2023. The first clinical trial will test the antiviral Paxlovid – which has shown some efficacy in early studies – against a placebo.

Many researchers are building up evidence to show that the virus hiding in patients’ bodies is driving long COVID. That could make the virus itself, or bits of it, a biomarker for long COVID.

Mass General’s Walt used a sensitive test that could find much smaller bits of the virus than traditional tests can. In a sample of about 50 patients, he found 65% of long COVID patients had bits of the spike protein from the SARS-CoV-2 virus in their blood. Although the study was small and preliminary, he sees the presence of the spike protein in the blood as a clue.

“If there were no virus present, there would be no spike protein because the lifetime of the spike protein after somebody has eliminated their viral infection is very short,” says Walt. “There has to be a continuous production of this spike protein from active virus for this spike to keep circulating.“

A private research collaborative in California is looking for the persistent presence of the virus in organ tissues. Researchers at the PolyBio Research Foundation study complex chronic inflammatory diseases like myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and now long COVID, which often produces the same symptoms.

Michael VanElzakker, PhD, co-founder of the group and a member of the Division of Neurotherapeutics at Massachusetts General Brigham Hospital in Boston, focuses on the possibility of a viral reservoir – a place where the virus can hang out and elude the immune system. If it is there, his team wants to find it and find out what it is doing, VanElzakker says.

“All successful pathogens evade the immune system in some way,” he says. “They can’t find little niches where they do that very well.”

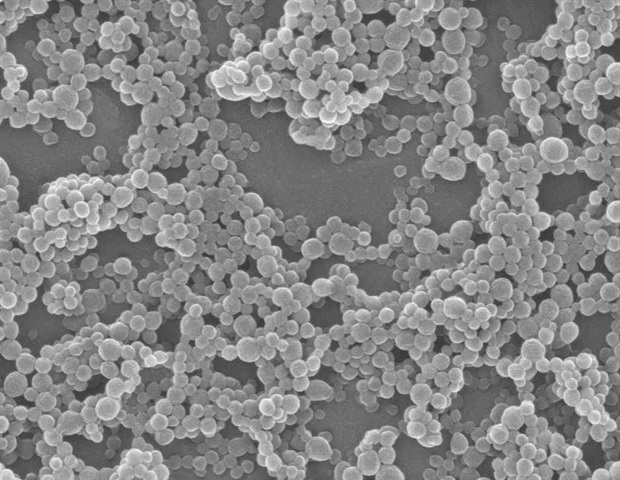

Microclots – small blood clots – are another sign of long COVID. A group of researchers – #Teamclots on Twitter – is studying them. One theory is that inflammation promotes the clots, which disrupt tiny blood vessels and prevent oxygen delivery. A possible trigger: the spike protein.

Signs of inflammation could themselves be used as biomarkers. Peluso and colleagues found in 2021 that long COVID patients had higher levels of inflammatory chemicals called cytokines. Measuring these cytokines helps explain the causes of long COVID, Peluso said during an online RECOVER Initiative update in November.

Similarly, Yale researchers reported in August that cortisol – a stress hormone – was uniformly lower than normal among long COVID patients.

The rise of ever new COVID variants has complicated research. Much of the early research was done before the rise of the Omicron variant. Walt said he found spike protein in fewer Omicron long COVID samples – closer to 50% than 65% – and researchers have found fewer clots in Omicron patients, who also had a milder disease.

Like some of the other scientists focused on long COVID, Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen, PhD, started out looking at another virus, in his case HIV. It can sometimes damage the lining of the intestines, causing what’s known as leaky gut. Abdel-Mohsen, an associate professor at the Vaccine & Immunotherapy Center at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, thought long COVID patients might have leaky gut syndrome, also.

Abdel-Mohsen and colleagues found evidence that microbes had leaked out of the intestines of long COVID patients and caused inflammation elsewhere in the body, including, perhaps, the brain. But it’s possible to treat this condition with drugs, he says. Checking for evidence of such leakage could not only provide a biomarker, but a target for treatment.

“There are many steps to interfere therapeutically and hopefully decrease symptoms and enhance the quality of people experiencing (long COVID),” he says.

While research looking at biomarkers is in its early stages, the hope is to find a biomarker that points to a treatment.

“The holy grail of biomarkers are really surrogate markers,” Peluso said during November’s RECOVER briefing. “What a surrogate marker means is you identify the marker, you identify the level of the marker, and then you do something to change that. And changing the level of the biomarker results in a change in the clinical outcome.”

In other words, something similar to a statin drug, which lowers levels of bad cholesterol – something that, in turn lowers stroke and heart attack rates.