For the insurance industry, Canada’s record-breaking wildfire season should raise the question: Can we blame people for where they live?

Amid mounting wildfire risk, consumers need incentives from their insurers to apply retrofits that can protect their house from fire embers, wildfire experts at CatIQ Connect in Toronto emphasized.

The problem lies in the fact that urban communities are gradually encroaching on forested areas, which makes homeowners more vulnerable to increasingly fierce wildfires.

Yet, Canadians seem to have forgotten one thing: boreal forests are meant to burn.

“That’s just sort of the natural way that humans want to live — immersed in the forest,” said Eric Robinson, director at Aon Impact Forecasting. “They want to feel like they’re part of that nature experience.

“Part of it is also figuring out, ‘Okay, [it’s] human desire to live in this environment. How do we then satisfy that and keep people safe?”

The discussion harkened back to an oft-quoted discussion point by the industry that, sometimes, it’s better not to rebuild in peril-prone areas.

But P&C insurers’ value lies in their ability to create policies and incentives that protect consumers before disaster — despite where they live, one expert suggested.

“Can we blame people for living where they live?” posed Michael Young, vice president, model product management at RMS. “That’s an easy thing for this industry to kind of fall back on.

“There’s no way that people know that they’re building in a floodplain, deliberately,” he said, by way of example.

“As an industry, we’re offering a product that helps people recover quickly,” he added. “We have to find those mechanisms to provide those incentives to promote the best behaviour [for mitigation].”

Fires grow forests — and damage homes

In Canada, first responders don’t try to suppress all wildfires. That’s because there’s a natural perimeter where wildfires actually create ecological balance to the forest, explained Mike Wotton, research scientist with Natural Resources Canada.

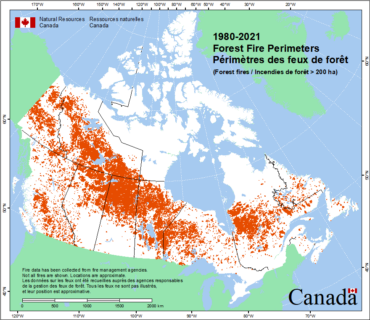

Canada’s forest fire perimeter is approximately the same as the boreal forest perimeter. Map: Natural Resources Canada,1980-2021 Forest Fire Perimeters.

Wildfire in Canada’s boreal forest usually takes the form of high-intensity crown fire. This type of fire spreads from tree to tree and is the most destructive.

Once burned, these forests regenerate from the dispersal of seeds dropped from burnt trees. “In doing so it also triggers regeneration,” he said. “The species in our forest, for the most part, encourage crown fire behaviour.”

The problem is, “even our really heavy water bombers can’t directly impact [crown fires], said Wotton, who’s also an associate professor at the University of Toronto.

What causes burns

But as Canada’s population grows and new builds keep going deeper and deeper into forests, homeowners’ risk urban conflagration, where wildfire moves from man-made structure to structure, rather than tree to tree.

When crown fires occur, wind can carry flaming pieces of debris, i.e. embers. If enough embers accumulate nearby, it can burn down a house.

There’s also a connection between wildfire ignitions and human development, explained Young. “Sixty per cent of ignitions in Canada are human-related, which means that there is a strong correlation with population.”

But wildfire damage to structures tends to be binary, Robinson. “So, either your structure burns, or it doesn’t.”

There are two reasons why homes don’t burn.

“It’s, one, keeping the flame from getting to your property in the first place — or making sure that flame is quite short by the time it gets there — or two…preventing ember accumulation and the efficiency of ignition through embers,” he said.

Often it comes down to the mitigation that homeowners do before a wildfire occurs that determines whether their house will go up in flames.

“It’s really about breaking that continuity of fuels from one place to another, and also managing the fire size,” said Robinson.

Building better to begin with

However the ignition is caused, it’s evident homeowners are increasingly underinsured and overexposed to wildfire damage. Insurers and other stakeholders must grapple with the best way to design a home to withstand wildfire.

Site-based mitigation can be carried out by insureds to lower the risk of their property burning.

One way of doing this is by creating a defensible space, said Robinson. “You’re trying to clear out basically all or most flammable fuel…[around] your property.”

This tends to be relatively low cost and is meant to protect the space surrounding your house.

Start by removing trees and potted plants from the area, cleaning gutters of leaves, and ensuring decks and patio furniture are not flammable (i.e. wood). This should be done within about 1.5 meters of the house.

“Then as you go out away from your property, you’re basically allowing a little bit more leniency,” said Robinson.

“Nobody wants to live in a completely treeless concrete desert,” he said. “We can have more tightly bundled trees, but we want to make sure we’re doing that in an incremental fashion and we have at least 30 feet — that’s 10 metres — of defensible space around the property.”

The next way of mitigating structure burns is through building hardening. This could include retrofits, or other investments to a property that make it more resilient to fire.

Combustible fencing leading to a property is one example of building hardening that can be done to prevent fire damage.

“How many of you know for a fact what roof type all of the properties that you’re insuring are? What [the roof’s] age is? Whether or not the vents are screened with three millimetre-sized, fireproof screening?” Robinson posed to the audience.

“Materials are really important,” he added. “There’s a big difference whether or not you have wood shakes on your house — that’s a big no-no — versus something that’s called a Class A rating fire roof.”

Complex roof shapes, which have interior corners, can also allow embers to accumulate. Flat roofs are also an issue for the same reason.

Robinson noted that insurers don’t often gather information on how policyholders are limiting their wildfire risk, either through building hardening or site-based mitigation.

“There really needs to be an effort for people to go out and ask for this information, record it, keep it with the policies so that we can manage it better,” he said. “You also need to make a financially smart decision as an insurer on how to offer proper credits for this. And it starts with collecting the information.”

A helicopter carrying water flies over heavy smoke from an out-of-control fire in a suburban community outside of Halifax that spread quickly, engulfing multiple homes and forcing the evacuation of local residents on Sunday May 28, 2023.THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darren Calabrese