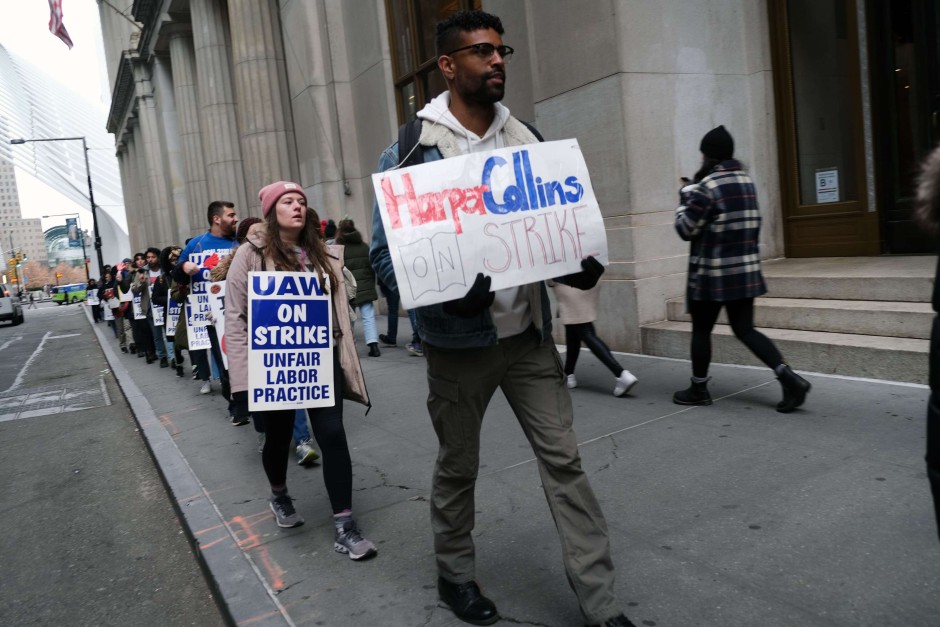

“We can’t pay bills with passion” is on their signs: 250 employees of the HarperCollins publishing house have been on strike in New York since the beginning of November for better wages. The editors, graphic designers and clerks are pretty much alone in this, since there is no union representation in most publishing houses in the USA. HarperCollins, which is one of the “Big Five” of English-language publishing houses, has so far refused to negotiate at its headquarters.

Working on books is too cheap

The UAW 2110 (United Auto Workers, Technical, Office and Professional Union) wants the company to spend about $1 million more a year on wages. The gross starting salary should increase from $45,000 to $50,000. The employees also want the publisher to hire more non-white employees. UAW representative Laura Harshberger called management uncooperative. The publisher, which has around 4,000 employees worldwide, achieved sales of $39 million in the third quarter of 2022 alone, but only wants to spend tens of thousands more on salary increases.

In New York, the culture and publishing industry is a popular field for expensively trained people from wealthy families. In a city where a room in a shared apartment costs a thousand dollars or more, $45,000 before taxes is hard to support a family – especially when there are thousands of dollars to pay for personal pension plans and tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in student debt. The median income for New York City is given as $67,000 to over $100,000, depending on the calculation basis.

“I’ve always had part-time jobs, and that’s how a lot of people do it,” says Faith Black Ross, for example, about her years at various publishers. Today she is a freelance editor and earns more than in the companies. In the beginning, she got $24,000 a year from a publishing house and always lived in shared apartments – at a time when a room in neighboring Jersey City was still available for $400. Union representation “didn’t even occur to her and her colleagues,” says Ross. She doesn’t want to go so far as to say that everyone who goes into publishing comes from a wealthier family, but there are a lot.

Some of the poor no longer want to put up with their situation. That’s why others from the industry are now showing solidarity. More than 150 literary agents signed an open letter saying they would no longer work with HarperCollins until the company entered negotiations. One of them is the writer and literary agent Danya Kukafka. As a best-selling author for HarperCollins, she was “horrified” that the strike had not received any response from management, she wrote in an email to the publisher shared on Twitter.

HarperCollins is the only major house whose employees are unionized at all, in eighty years. There is no general right to do so in the United States. Regulations vary from state to state. Workforces usually have to vote to ensure that a union is allowed in their company. Many employers campaign against such efforts, often hiring union busting law firms that specialize in intimidating wage earners.

In the publishing industry, such campaigns as have already occurred at T-Mobile USA or Volkswagen are not even necessary. In many publishing houses, the employees have never tried to organize themselves; but strikes at universities are also currently having an impact on the cultural scene. At the University of California alone, 48,000 workers recently walked out in favor of better wages and working conditions. The next publishing strike could also be this week, with a thousand New York Times employees threatening a 24-hour strike if their demands for higher wages and better health and pension plans are not met.