In this interview, News-Medical speaks to Henry Fingerhut, Senior Policy Analyst for Science & Innovation at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, about genomic surveillance and its associated opportunities and challenges. In collaboration with Professor Derrick Crook of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Medicine, Henry recently published Global Governance of Genomic Pathogen Surveillance, a paper outlining the recent history and future opportunities at the international level.

Please can you introduce yourself and tell us about your professional background and your current role at the Institute for Global Change?

I’m a Senior Policy Analyst for Science & Innovation at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. I come from an interdisciplinary background. At TBI, I work on a range of technology policy issues, including health, biotechnology, and UK innovation policy, with the aim to help governments leverage technology for social good.

Most recently, I completed my Ph.D. in Technology, Management, and Policy at MIT with research on how healthcare providers use Evidence-Based Practice and incorporate new technologies into clinical care.

As part of The Global Health Security Consortium, the Institute for Global Change advocates for a comprehensive approach to genomic surveillance. Could you explain the process of genomic surveillance, its importance, and how it aids global public health security?

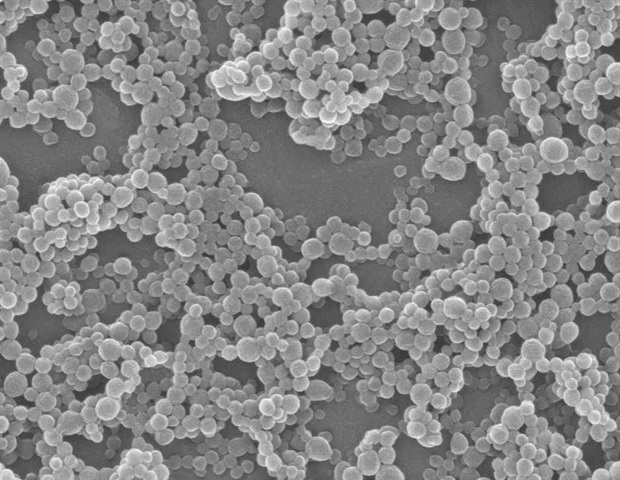

Genomic pathogen surveillance systematically identifies and tracks pathogens to understand how they develop, mutate, and spread. This process includes all the steps from the swab—when a sample is taken from an infected individual—to public health decisions. It incorporates 1) sampling potentially infected individuals, 2) sequencing that sample to get the underlying pathogen’s genome, 3) a series of systematic data analysis steps to isolate the pathogen’s genome, remove personally identifiable information about the patient, and compare it to other pathogens, 4) and storing and sharing that data among labs and public health officials to generate public health insights.

Image Credit: Explode/Shutterstock.com

Genomic surveillance complements the current public health infrastructure to help public health officials quickly identify and evaluate new pathogens and variants of concern. A comprehensive global network with sequencing and data analysis capabilities worldwide, as well as the governance standards to ensure the data is analyzed consistently and shared ethically, would help alert officials at the national and global levels about new outbreaks and variants. It would also help researchers and pharmaceutical companies understand pathogen dynamics and develop effective treatments.

Genomic surveillance has been an integral part of managing the COVID-19 pandemic. How has genomic surveillance and its associated technologies/sequencing methods changed since the start of the pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic helped call global attention to this need and rapidly advanced global initiatives. There has been a range of philanthropic initiatives to build out genomic sequencing capacity in low- and middle-income countries during COVID-19, and the WHO’s new Berlin Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence and 10 year strategy for global genomic surveillance, both launched in the past year, will help build out this critical infrastructure post-pandemic to monitor other pathogens and related concerns like TB and anti-microbial resistance.

In your study entitled “Global Governance of Genomic Pathogen Surveillance,” you discuss the opportunities and challenges within this field. What are the current challenges of the global governance of genomic pathogen surveillance, and how may these challenges be overcome in the future?

We outline three challenges in the paper: governing the ethical and geopolitical concerns around genomic data sharing, setting and adopting technical standards, and scaling capacity across the globe. These each require global cooperation and trust-building, particularly to ensure technical providers or beneficiaries of data sharing, often from high-income countries, respond to the concerns of low- and middle-income countries who contribute data to the network. But as we highlight in the paper, structures like the new WHO Hub will play an important convening role in bringing together an effective and responsible global network.

Global public health security includes proactive approaches to minimize public health disasters like pandemics. How can genomic pathogen surveillance help healthcare professionals in their pandemic preparedness.

Genomic pathogen surveillance can help public health officials and healthcare professionals in pandemic preparedness. For public health officials, a well-designed genomic surveillance network will help quickly identify new pathogens and variants of concern, track their population dynamics within and across countries, and—when linked securely and anonymously to routine clinical data—monitor their virulence and symptomatology.

Image Credit: Blue Planet Studio/Shutterstock.com

For healthcare professionals, this data could also help inform diagnosis and treatment decisions, both by access to that public health data and hopefully by developing precision treatments targeted to a specific pathogen variant.

Generally, the COVID-19 pandemic indicated how important it is to coordinate and collaborate across the research, clinical, policy, and public health spheres to improve health outcomes – to do so requires the infrastructure to share data securely and anonymously. Genomic pathogen surveillance is one piece of that puzzle and could help to establish best practices for cross-sector collaboration broadly.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted patterns of global health inequality. How can health innovation policies improve health inequalities, especially regarding scaling genomic sequencing worldwide?

As we highlight in the paper, the global genomic surveillance community has been responsive to valid concerns of health inequality in the past decade, raised especially by low- and middle-income countries—most notably Indonesia in 2008. It is essential that vulnerable populations be represented in data collection to enable us to learn how pathogens spread among different groups and how their symptoms develop.

But it is also important that this data collection and sharing be done responsibly, with attention to their autonomy, engagement as partners, and benefit-sharing. The 2010 Nagoya Protocol secures many of these principles of fair and equitable benefit-sharing, but it will be essential to develop mechanisms to build local capacity and share benefits effectively.

You work in collaboration with the Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine and the University of Oxford. How important is collaboration between partners when addressing global public health issues?

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how important collaboration is in global public health – including across the academic, policy, and private sectors and at the local, national, and global levels. The GHSC is a new kind of partnership, bringing together political, scientific, and technological expertise to drive progress in global health – and with this paper, we wanted to highlight the need for such cooperation in global genomic surveillance.

Of course, collaboration at this scale brings challenges. Still, we hope this paper helps identify some ways forward for a critical modern infrastructure that can not only future-proof us against pandemics but can also build far greater capabilities in the fight against communicable diseases and help revolutionize microbiology.

What are the next steps for The Global Health Security Consortium and its ongoing work within genomic pathogen surveillance?

We have a handful of initiatives in this area, ranging from thought leadership to facilitating cross-sector partnerships to move forward global genomic surveillance efforts. This includes looking at how national governments can build genomic surveillance capabilities and engage in effective, mutually beneficial data sharing. But it also includes engagement at the international level to ensure momentum does not slow as political and public focus on the pandemic subsides.

We’ve come a long way in accelerating digital infrastructure in response to COVID. Still, there is a significant opportunity to build 21st-century technology that cannot only help us fight against future variants and pandemics but has much wider potential impacts, including in areas like TB. It is an opportunity we need to take: the health and economic benefits of doing so will likely be substantial in the future.

Where can readers find more information?

You can find more information about the Global Health Security Consortium and current initiatives here. And the Tony Blair Institute is also working on a range of policy issues more broadly, including health and biotech, available here.

About Henry Fingerhut

Henry is a Senior Policy Analyst for Science & Innovation at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. He comes from an interdisciplinary background at the intersection of science and policy.![]() In particular, he focuses on how social and political factors impact scientific projects (like the genomic pathogen surveillance initiatives) and how technical details can impact policy outcomes. At TBI, he works on a range of technology policy issues, including health, biotechnology, and UK innovation policy, with the aim to help governments leverage technology for social good.

In particular, he focuses on how social and political factors impact scientific projects (like the genomic pathogen surveillance initiatives) and how technical details can impact policy outcomes. At TBI, he works on a range of technology policy issues, including health, biotechnology, and UK innovation policy, with the aim to help governments leverage technology for social good.

Prior to joining TBI, he completed my Ph.D. in Technology, Management, and Policy at MIT with research on how healthcare providers use Evidence-Based Practice and incorporate new technologies into clinical care.