After a severe NatCat year in Canada in 2022, all signs point toward warmer, drier conditions in 2023 and a quiet hurricane season.

With that, however, meteorologists predict this year will make Top 5 list for warmest years on record and will exacerbate drought across Canada, one expert said at Cat IQ Connect.

Nevertheless, “prepare for the expected, and most importantly, the unexpected,” said Steve Bowen, chief science officer at Gallagher Re. “There’s always going to be anomalous events.

“The next Cat doesn’t wait for us to be prepared,” he added, which is why knowing your risk is critically important.

ENSO and hurricanes

In 2023, Bowen said all eyes will be on El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which affects weather conditions worldwide.

“We have been in the midst of what we call a triple-dip la Niña, which is three consecutive rolling [calendar] cycles of La Niña conditions. And that does not happen very often, it’s actually a pretty rare occurrence.

“And we’re actually going to be transitioning to an El Niño by the end of the year,” he said.

In November 2021, La Niña conditions brought forth an atmospheric river (i.e., a jet stream of moisture) into the Pacific Northwest that led to B.C’s worst floods in the province’s history, but with ENSO approaching, “it’s going to essentially be potentially the opposite for central and western Canada.”

Peak ENSO conditions occur during the winter and early spring months and cause warmer and drier conditions, especially in the central and western parts of Canada. In contrast, La Niña causes cooler, wetter conditions.

Month by month, temperatures are expected to moderate in 2023 — a signal that El Niño will pick up in place of La Niña.

The good news is that current model forecasts predict a ‘near average’ hurricane season. Plus, with El Niño comes fewer storms and less opportunity for activity to reach Canada, Bowen said.

However, it’s no guarantee. Hurricane Andrew, a very powerful and destructive Category 5 Atlantic hurricane, occurred in 1992 — an El Niño year.

“That was meteorologically one of the more quiet hurricane seasons that we’ve seen. But again, that one storm makes all the difference,” said Bowen. “Conditions, if they do shift to El Niño by the peak of the hurricane season, should be a bit more favourable for less storms, but again, it only takes one big one.”

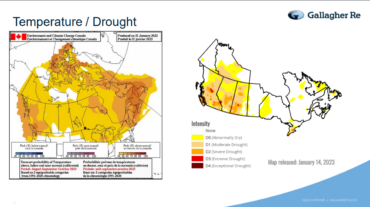

Temperature and drought

The good news is the precipitation and flood outlook in 2023 is appearing ‘pretty normal,’ Bowen said. “Generally, we’re not looking at too much above normal or below normal [precipitation].”

The bad news is temperature and drought will pose a bigger problem, he said.

With El Niño years leading toward warmer and drier conditions, especially in western parts of Canada, “you can see pretty consistently that it’s looking like it’s going to be a pretty hot and toasty summer,” Bowen said.

Image by ARTHUR J. GALLAGHER & CO

Forecast probability shows above normal drought conditions across the country from August to October — from the west coast to Atlantic Canada, and even the northern territories — as per Environment and Climate Change Canada.

This is not particularly good news, given that B.C through to Saskatchewan experienced abnormally dry to moderate drought conditions as of January 2023.

“We’re very likely looking at an, at least, Top 5 warmest year on record and it very likely will be even more than that,” Bowen said.

This could have negative implications for crop farmers, who already suffered drought conditions in 2022.

“If we do get a year where we don’t get enough precipitation, that really could amplify drought conditions and really be affecting some of the agricultural practices that are going on across the country.”

Severe convective storm

Certain severe convective storm (SCS) events, namely hail, will be a given regardless of ENSO conditions, said Bowen. “It’s very likely…there’s going to be a guarantee of a big hail event somewhere. It’s just what happens, especially in parts of Alberta.”

Tornado predictions, however, remain consistent with previous years’ patterns.

Across Canada, prairie provinces and the southernmost parts of Ontario are most likely to see frequent and intense tornados compared to the rest of the country, according to both a tornado simulation and an Environment Canada tornado study from the last decade.

“Better building codes, putting hurricane clips on structures can actually limit a lot of the structural potential damage for the lower-end tornadoes. And the…highest frequency of tornadoes tends to be those lower-end events, like EF-0, EF-1,” he said.

“These are the areas where I think we really need to be emphasizing the need to be protecting ourselves for the inevitable convective activity that is going to occur.”

Feature image by iStock.com/Marccophoto