Wildfires in Canada are a natural process but since they can be so devastating to communities, people need to be better prepared for their inevitability, say keynote speakers at Cat IQ Connect in Toronto Tuesday.

That’s why more focus must be placed on solving and preventing losses before they occur, the speakers said.

In the U.S., just 3% of fires cause nearly 88% of losses, said Ralph Bloemers, director of fire safe communities at Green Oregon. Los Angeles’ Palisades region, which was destroyed by wildfires in early 2025, “has a long fire history of many known fires in this exact same location,” he said. “That’s why I think [the] message of, ‘Prepare for the inevitable wildfire, don’t deny natural realities,’ is the exact message that we need to accept.”

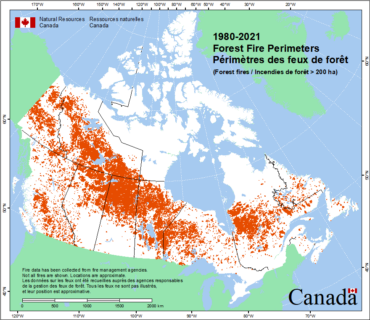

Canada’s own forest fire perimeters largely chart the same path as the boreal forest. When burned naturally, these forests regenerate from the dispersal of seeds dropped from burnt trees.

Canada’s forest fire perimeter is approximately the same as the boreal forest perimeter. Map: Natural Resources Canada, 1980-2021 Forest Fire Perimeters.

Thus, the term “wildfire” is a misnomer, says Tyrone McNeil, president and tribal chief of Stó:lo Tribal Council in B.C. When settlers arrived in Canada, they called non-farmable lands ‘wild,’ which led to the idea that the forest could be tamed.

“I mean, we don’t say wild rain and wild flood and wild hurricane. We just know that they’re forces, right?” Bloemers added.

However, Canada has warmed by 2 C since pre-industrial times — that’s double the global average. Canada’s northern territories are warming three times as fast. The warmer and drier temperatures are making fires more severe, which makes it harder to predict their perimeters.

“The reality is, we can’t FireSmart a forest. It’s completely impractical,” McNeil says.

(FireSmart programs, like the one in B.C., are designed to support wildfire preparedness, prevention, and mitigation in the province.)

That said, mitigating fire risk is still possible, the speakers said. Homeowners can take measures to protect their properties from forest fires. Many just don’t realize how simple these steps are.

Bloemers, who started his career with Munich Re, recalls the sage advice his father, who also worked in insurance, gave him: “Sell the policy and then go in and reduce the risk.”

Added Bloemers: “The role that you insurance folks can do is send letters to your policyholders saying, ‘Hey, we’re here for you, but you’ve got to self-insure. You’ve got to do the mitigations that matter if you want to keep this policy, and you’ve got to do it on the community scale.’”

Reducing the risk

What mitigation efforts matter the most?

Removing the pathway for fires and limiting preventable ember ignitions, says Bloemers.

The keynote speakers say the most effective fire adaptation measures homeowners can take are equivalent to a “weekend project.”

For example, they can:

- Remove vegetation and other combustibles closest to the house or property

- Replace vents with fire-safe ones

- Remove attached fences from homes

- Remove overhanging branches and combustible mulch.

These measures are most effective because embers are the primary cause of ignition. And these embers are carried by wind-driven fires to flammable objects on or near the house. The L.A. wildfires, for example, were fuelled by exceptionally dry conditions and high winds.

It’s simple and cost-effective enough for homeowners to retrofit their homes accordingly, says McNeil. But he hopes Canada’s building code will be updated to reflect the risk for new homes, too.

“That’s the beauty of the new build aspect to it. If you do this from design, it doesn’t cost anything, even the retrofitting to do this doesn’t cost you a great amount,” he says.

“There’s no doubt we need to make every effort to retrofit and accommodate the fire when it comes, and accommodate in a way to limit or restrict or prevent harm, absolutely,” says McNeil. “[But] I hope at some point much sooner than later, building codes are modified to fully align with an issue like this.”

These property-based efforts are much more successful than fire control and forest management measures in preventing wind-driven fires, he said.

For example, some communities attempt to thin tree lines or remove trees altogether in the areas surrounding their townsite. The goal is to create a “fuel break” between the path of the fire and the community.

But these efforts are costly and often fail, says Bloemers.

“They might provide some benefit in non-wind-driven events to mitigate the intensity of the fire, and they might provide some benefit in intense fire behaviour. But more and more experts [are] saying that thinning around the community actually reduces friction and increases wind speed and possibly increases ember cast.”

Plus, these fire control measures create new risks.

Prolonged smoke or exposure to fire can have a profound human impact, creating health issues and even causing death. That’s why it’s essential for homeowners to “self-insure,” by doing their own fire mitigation efforts, thus preventing the need for risky and often ineffective firefighting measures during wind-driven fires, said Bloemers.

It takes an average of five to 20 firefighters to respond to a single event, he adds.

“We need to basically become our own heroes by doing the mitigations in our community before fire comes, to give [firefighters] an ability to defend the houses that weren’t mitigated and prevent structure destruction,” Bloemers said.

In this long exposure photo, embers fly from burning trees as the Caldor Fire grows on Mormon Emigrant Trail east of Sly Park, Calif., on Tuesday, Aug. 17, 2021. (AP Photo/Ethan Swope)