In this interview, News-Medical talks to Dr Javier Yugueros-Marcos, Head of the Antimicrobial Resistance and Veterinary Products Department at the World Organisation for Animal Health, about how the world can work together to promote the sustainable and responsible use of antimicrobials.

Please could you introduce yourself and tell us about your role within the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH)?

My name is Javier Yugueros-Marcos, and I joined the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, founded as OIE) one year ago in November 2021. I am leading the department in charge of the quality of veterinary products, which encompasses diagnostics, vaccines and therapeutics, including antimicrobials. Because of the importance of antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistance, about 80% of our activity revolves around them.

We monitor antimicrobial use all over the world, develop standards on the responsible and prudent use of antimicrobials, and assess the quality of actions in the field so that we can increase capacity-building and change practices.

WOAH’s mission is to help create a future in which humans and animals benefit and support each other for a healthier, more sustainable world. Why is this mission so important given the current state of global health, and how is the health of humans and animals interlinked?

Our work began in 1924 after an animal disease had a big impact on food security: Rinderpest. Since then, we have been working on improving animal health worldwide, bringing about transparency in terms of the status of animal health, and ensuring safe international trade of animals and animal products. All of this leads to better health for humans.

Today, the situation is not much different because animal diseases still exist, and we still care about transparency and reporting animal disease outbreaks for safe international trade. However, human and animal health are interlinked in terms of more than just international trade. Let me give you two examples.

One is zoonoses. It is estimated that 60% of infectious diseases in humans originate from animals. This percentage is increasing to three out of four, when talking about emerging pathogens. Notable examples include Ebola virus, Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and the first generation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV). We suspect the same for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus behind COVID-19, although we have not identified the intermediate species yet, if ever.

It is not only food-producing animals that humans risk contracting disease from, but also wildlife. And vice versa, as diseases can also be transmitted from humans to animals. Human population expansion is displacing animals from their environment, and the new contact that humans have with these displaced wild animals increases the risk of zoonotic disease occurrence and transmission.

The second example is antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is the main topic of this interview. Pathogens have no borders, and the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials in any sector will immediately impact the others. When tackling this problem, it does not make sense to monitor the responsible use of antimicrobials in humans if we do not collect the same information in animals, and vice versa. Everything is connected. As long as we do not work together in this interconnected world, we will not be able to solve its problems. It took us a while, but I think that many stakeholders are finally acknowledging that.

World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, founded as OIE) – It’s Everyone’s Health.

Improving global health and well-being can only be achieved by also considering animals and the environment. How will the improvement of animal health consequently improve the health of humans and the environment?

Consider the examples I have just given of infectious human diseases coming from animals. Improving animal health will prevent many of these events from happening and will eventually ensure that we have a healthier human sector. This includes not only food-producing animals and wildlife but also companion animals which are increasingly present in our lives.

The other aspect of all this is to consider how dependent we are on animals for our livelihoods. Today, one out of five people depend on production animals for their income and livelihoods. This is not so evident in high-income countries, but it is highly present in low and middle-income countries which represent a huge proportion of the global population.

Whenever we talk about animals, we tend to think about terrestrial animals, but we also have to think about aquatic animals. Over 20 million people depend on the aquaculture sector. This is the fastest growing sector of those supplying protein for the world.

Every year you and your partners at the WHO, the FAO and UNEP celebrate World Antimicrobial Awareness Week. The theme for 2022 is “Preventing Antimicrobial Resistance Together”. What does this theme mean to you?

There is no more effective way to avoid antimicrobial misuse than employing them only when other approaches do not work, only when they are necessary. Prevention is the first thing that we have to bear in mind. We have to maximise the technologies existing today to improve biosecurity and ensure best-in-class animal husbandry practices. One way this is well underway is through the use of vaccination across the sectors.

Before this, I was working in the human health sector, so I am accustomedto promoting the term ‘hygiene’. Hygiene is the best way to prevent infection. And we have seen this with the recent COVID-19 pandemic, where we employed social distancing, hand sanitizer use, and other measures. Thus, hygiene was enhanced. The same applies for animals. And it is not only our hands that pose a risk – for example, farm workers need to think about changing their boots when they go into the farm, and checking visitors when they come onto the property.

All these factors, as well as how animals are raised and live, affect their capacity to fight infections. Maximising their immunity prevents them from getting sick, preventing all of us from using more antimicrobials.

This is something that has been somehow forgotten, and we would like to emphasise this message. Simple and easy measures can save a lot of trouble down the road.

Image Credit: World Health Organization

With antimicrobial resistance being described by WHO as one of the top 10 threats to global health, what impact is it actually having on animals worldwide?

We would like to be as advanced as our colleagues from the human health sector in this regard. Unfortunately, there is currently no data available on the burden of antimicrobial resistance in animals at global level, but we are working on it.

There are several regional initiatives (i.e. Europe, Asia, Americas…) collecting data on the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in the animal health sector. But as I said, we do not have any comprehensive global data yet. Our colleagues from FAO are working on this. This year they have started a pilot to collect data on antimicrobial resistance in animals. They are beginning in Asia, and their goal is to collect data globally by the end of next year.

The other initiative that I wanted to mention is one that we are leading in collaboration with the University of Liverpool, which is called the Global Burden of Animal Diseases (or GBADs). It follows the same methodology as something that was done for humans a few years ago. We have recently developed a component on the economic impact of AMR in animals, particularly the socioeconomic impact on livelihoods where antimicrobial resistance is present.

One key objective of World Antimicrobial Awareness Week is improving awareness of AMR. Despite continued awareness, many people still do not fully understand the wider implications it has not only for human health, but for animal health and environmental health. What more can people and policymakers do to continue educating about this global health threat?

There are a couple of basic things that we must keep doing. One is repeating. Education is the simple exercise of repeating things. Something that we are starting to work on is making the messages evolve and targeting populations where the message can trigger actions.

We were discussing this with our Quadripartite colleagues (the Quadripartite alliance for One Health: FAO, UNEP, WHO and WOAH) a few weeks ago. One of the populations that were identified as powerful drivers of communication is the youth and children in particular. They learn everything; they listen to everything; they repeat everything that we can teach them. They represent the future. If we succeed in educating them and making them understand that antimicrobials do not have to be overused or misused, then we will be achieving a level of understanding that has not been gained until now.

In this regard, we have already engaged with young people and students. For example, we will participate in the upcoming Global AMR Youth Summit, organised by the World Health Students Alliance and taking place during the World Antimicrobial Awareness Week.

In terms of targeting populations and adapting the messages, we are currently working on renewing our web content and making it more understandable for non-technical populations, for example, concerned citizens.

In terms of the policymakers, the two actions needed are 1) bringing them the data to showcase that there is a problem, and 2) providing alternatives. It is then our responsibility as an organisation to set standards on how antimicrobials can be used responsibly and prudently. These recommendations are then used to guide the development of national regulations or legislation.

We are working on expanding the breadth of actions from food-producing animals to all animals, companion animals and wildlife included. We are making the role and the responsibilities of every actor within the chain much clearer, from the veterinary authorities to the farmer and pet owners. We are providing these overarching principles that in the end can be translated into legislation or regulation, and therefore have an action in the field. It is also within our responsibility to highlight the priority research areas for research agencies and countries to fund so that in the end we can provide alternatives to antimicrobials.

©World Organisation for Animal Health

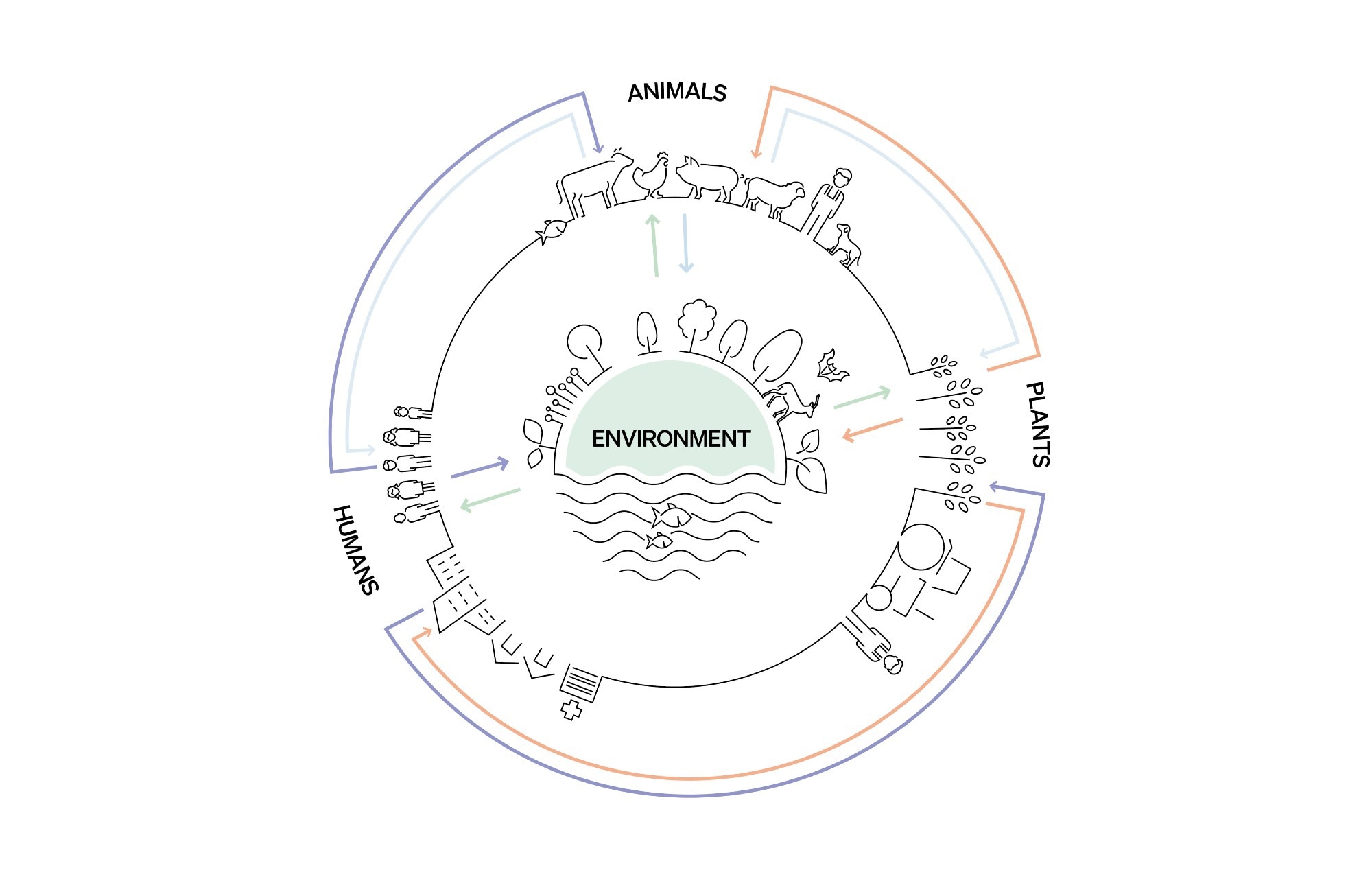

It has been described that to work collaboratively between sectors to tackle AMR, we need to use a One Health approach. What is meant by the term One Health and what are its advantages for global health?

One Health, in very simple words, is about working together. We are all interconnected. What is happening in the animal health sector is eventually going to impact the human sector. And the behaviour of humans has an impact on the animal health sector, as well as in food systems and ecosystems.

Translated into the world of governments, One Health is not much more than making all the sectors work together. We are trying to promote dialogue across sectors. At global level, the Quadripartite organisations have learned to dialogue, work together, and undertake actions in collaboration.

How will this level of international collaboration, especially between animal and human health professionals, help to tackle other problems such as rabies?

AMR is a health challenge and it can be taken as a model on how collaboration could improve our response. The same model can be applied to zoonotic diseases, those that may transmit from animals to humans, or humans to animals. When working on a human disease, if there is an animal component, we need to pick up the phone, write emails, and work with the department in charge of animal health.

The Quadripartite organisations have been working together on AMR since 2014/15. Today, AMR is one action track of the One Health joint action plan, which has been recently launched to advance One Health at global, regional and national levels. Our experience can be an asset to other people working in similar areas. AMR is a model, and then the model can be applied to other shared health challenges.

Alongside your current work surrounding antimicrobial resistance, what are some other priorities you are currently addressing within WOAH?

Our AMR strategy has four pillars: awareness, surveillance and research, capacity-building, and standards implementation.

In terms of awareness, this conversation is a good example. The World Antimicrobial Awareness Week, a global campaign to raise awareness and understanding of AMR and promote best practices among One Health stakeholders.

In terms of surveillance, we have a number of fascinating things ongoing. One is our database of worldwide antimicrobial use in animals, launched in 2015. For seven years, we have been using paper-based and Excel forms to collect the information from countries. This year marks a turning point, as last September we launched a totally digitalised system to allow countries to report and use their data for their own actions. The platform will become accessible for the public in the upcoming year.

At the same time, we are initiating a similar system for the detection of falsified and sub-standard products. The keys to antimicrobial stewardship are having the right antimicrobial for the right individual, at the right time, with the right dose, and for the right period. But it is also important to have the right product, because if products are falsified or sub-standard, inoculations are not going to have any efficacy, leading eventually to resistance. We are starting a pilot experience for a global system for alerting sub-standard and falsified products.

The other initiative that we have is the estimation of the economic burden of AMR. In terms of research, we are working with our Quadripartite partners, developing a One Health research priority agenda in collaboration with many different stakeholders. The goal is to provide a roadmap of priorities that should be tackled in terms of research from the One Health perspective.

Then, in terms of capacity-building, we support the Multi-Partner Trust Fund initiative in collaboration with our Quadripartite partners and the donors, which is today funding 10 low- and middle-income countries to implement their national action plans on AMR using a One Health approach. We have learned to talk to each other at global level, and we are scaling up these efforts at local level so that the Minister of Agriculture, the Minister of Health, the Minister of Environment, and the Minister of Aquaculture in a given country can do the same to successfully implement national action plans on AMR across the sectors. Kenya, Zimbabwe, Tajikistan and Morocco are examples of countries supported through this fund.

Last but not least, a strong legal framework is necessary if countries are to take effective action in the face of health threats such as AMR In addition to providing Standards on the responsible use of antimicrobials, we also have a programme on Veterinary Legislation Support (VLSP) that helps Members recognise and address their needs for clear, comprehensive veterinary legislation.

Image Credit: Pressmaster/Shutterstock.com

Are you hopeful that with this continued awareness, education and funding surrounding AMR, we will one day see a world without AMR?

I wish I could imagine such a world, but all organisms on Earth share the same planet and we are all connected. We all adapt to our environment. Antimicrobial resistance is a natural phenomenon that microorganisms implement to evolve in a hostile, toxic environment. As soon as they see an antimicrobial agent preventing them from thriving, they are going to develop resistance. Alexander Fleming warned us all when he received his Nobel prize. With every new antimicrobial that we have developed, sooner rather than later, resistance has appeared.

A world without antimicrobial resistance is difficult to imagine. However, we can learn how to live in a world where we can use antimicrobials sustainably and reduce the burden of human, animal and plant diseases. This is what we are working on. We are working on making every actor in the animal health sector aware that we must use antimicrobials responsibly to ensure they remain available for future generations.

Sustainability can be achieved by developing new antimicrobials, but also, more importantly, by using the ones that we have today responsibly.

This is where action for prevention is really important. If we encourage hygiene, improve security at farms, and keep animals in good conditions so that they have a strong immune system, then we can fight this battle and maintain low levels of antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobials must be used responsibly and sustainably.

With the COVID-19 pandemic reminding us that all sectors must work together to achieve scientific progress, we have seen significant advancements in recent years, especially within disease diagnostics. Are there any particular fields within animal health that you are excited to watch evolve over the coming years?

I think COVID-19 has also taught us about the power of vaccination. I hope that after the pandemic everyone will understand its importance in terms of prevention. Hopefully, it will help encourage trust and confidence in this practice.

Regarding diagnostics, I am a little biased, because I worked for 18 years in the field of diagnostics, and, as a former colleague used to say, “without diagnosis, medicine is blind”. This is true for the human health sector, but even more so for the animal health sector, which is severely impacted by the lack of diagnostic tools, particularly innovative ones. I hope that this area will be reinforced, thanks to development in human health being imparted into the animal health sector.

What is next for you and your work at WOAH? Are you involved in any exciting upcoming projects?

I have mentioned several already, but I will pick the three most exciting ones.

First, the launch of the global database on antimicrobial use in animals, called ANIMUSE.

The global burden of animal diseases is also an exciting project because it will give us an idea of the socioeconomic impact of animal diseases. I think it will help mobilise resources and ratify the importance of AMR in the animal health sector.

Finally, the revision of standards we are undertaking. We are expanding the content to other animals, not only food-producing animals, and clarifying the responsibilities of every actor to use antimicrobials responsibly. I am very confident that this will help in the field if people know who does what and how to do it properly.

About Javier Y. Marcos

Javier Y. Marcos has a solid history of working in antimicrobial resistance (AMR), with eighteen years of experience in the development and commercialisation of diagnostics tests for infectious diseases, both for human and animal health. Having graduated as a Doctor in Veterinary Medicine in 1997, he also holds a PhD in Microbiology & Molecular Biology from the Leon University, Spain.

At the end of 2021, he was appointed as Head of the AMR & Veterinary Products Department at the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, founded as OIE), being accountable for the enhanced quality of veterinary medicinal products, and the coordination of actions supporting a responsible and prudent use of antimicrobials in animal health worldwide.