By Carole Tanzer Miller HealthDay Reporter

FRIDAY, Aug. 12, 2022 (HealthDay News)

Farmyard pigs could be the key to restoring sight in people who have lost their vision due to a damaged cornea, a new study reports.

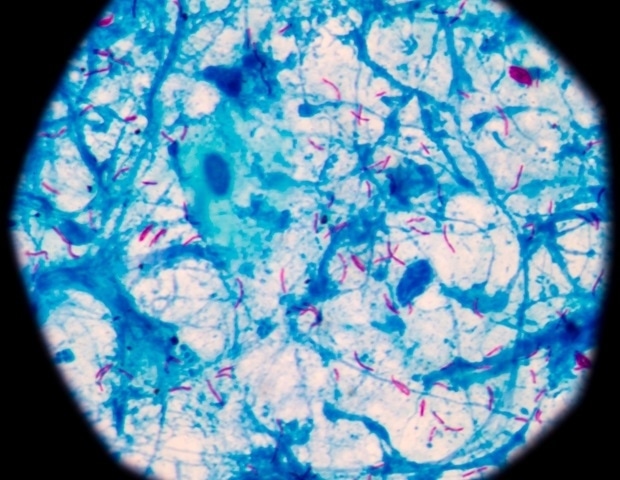

Collagen drawn from pig’s skin is being used to create an experimental implant that mimics the human cornea, the outermost transparent layer of the eye.

In a pilot study, this implant restored vision to 20 patients with diseased corneas, most of whom were blind prior to the procedure, researchers said.

The human cornea consists mainly of collagen. To create the implant, researchers distilled highly purified collagen from pig skin and then stabilized the loose collagen molecules to form a tough and transparent material that could be implanted into a human eye.

The implant could be a breakthrough in treating vision lost to cornea damage or disease, researchers said.

An estimated 12.7 million people worldwide are blind due to their corneas, and the only way to restore their vision is a cornea transplant from a human donor, researchers said in background notes.

But the donor supply is low, with just 1 in 70 patients receiving the transplant they need.

“We wanted to source a very abundant and inexpensive source of collagen, as our goal was that these implants could one day be mass-produced to meet the enormous demand for cornea tissue for transplantation,” said senior researcher Neil Lagali, a professor of biomedical and clinical sciences at Linköping University in Sweden.

“Collagen from pig skin is a byproduct of the food industry and is very abundant, and has already been used in [U.S. Food and Drug Administration]-approved products such as dermal filler,” Lagali said. “So it seemed an ideal material for a corneal implant.”

The pigs used in the process aren’t genetically engineered in any way. “They are normal, healthy pigs used in the food industry,” Lagali said.

What’s more, the implant actually runs a much lower risk of rejection than corneas transplanted from human donors.

“Because the collagen is highly purified and no cells or other biological materials are in the bioengineered corneas, it minimizes the risk of rejection,” Lagali said.

Researchers also came up with a new and minimally invasive way of using the implant to treat keratoconus, a disease in which the cornea becomes so thin that it can lead to blindness.

Keratoconus usually starts in childhood and progresses through the early teen years, Lagali said. As the collagen in the cornea gradually breaks down, the cornea gets thinner and loses its shape and ability to focus light.

About 0.1% of the U.S. population is affected by keratoconus, Lagali said, but the disease affects up to 2% to 3% of the population in countries throughout the Middle East, Asia and Australia.

“This means that in a country such as India or China, tens of millions of people have the disease,” Lagali said.

For a normal corneal transplant, the entire thickness of the cornea is removed and replaced with a human donor cornea that is then sewn into place, he said.

“Because it is foreign human tissue, the patient must receive immunosuppressive eye drops for at least a year or even longer, to avoid rejection,” Lagali said.

“With our method, we keep the patient’s own cornea, only making a small incision within it, and inserting a bioengineered implant,” he added. “The implant does not have cells so it does not trigger an immune response, and only an eight-week course of immune suppression eye drops is needed. No sutures are needed, so the procedure can be performed in a single hospital visit.”

Both the implants and the new surgical method were tested in Iran and India, on 20 patients with advanced keratoconus.

The point of the trial — which was reported Aug. 11 in the journal Nature Biotechnology — was to test whether the implant was safe to use in humans, but the results astonished researchers.

Prior to the operation, 14 of the 20 patients were fully blind. After two years, none were blind, and three had perfect 20/20 vision.

The implants have lasted at least two years without getting thinner, Lagali said.

“Our earlier work shows that collagen-based implants that are not as strong as the current material still last at least 10 years in the cornea,” he said. “Over time, the cornea’s own cells will take over and produce new collagen, so in the long term, the corneal tissue should regenerate.”

The implants also have one other advantage over donated corneas. They can sit on a shelf for up to two years before use, while donor corneas must be transplanted within two weeks, Lagali said.

“We need to conduct randomized clinical trials with a larger number of patients, so we are working on getting funding for that,” he said. “Once we can demonstrate this works in a randomized trial, then we will apply for authorization to market this as a product.”

QUESTION

What causes dry eyes?

See Answer

Dr. Christopher Starr, a clinical spokesman for the American Academy of Ophthalmology who reviewed the findings, said these early results are “quite promising.”

“As a corneal specialist who performs corneal transplants and takes care of many patients with keratoconus and other corneal disorders, I am thrilled by the results presented in this paper and hope this technique is eventually approved by our FDA,” Starr said.

The Swedish manufacturer of the implants, LinkcoCare Life Sciences, paid for the pilot study.

SOURCES: Neil Lagali, PhD, professor, biomedical and clinical sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden; Christopher Starr, MD, clinical spokesman, American Academy of Ophthalmology, San Francisco; Nature Biotechnology, Aug. 11, 2022

Copyright © 2021 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

;Resize=(1200,627)&impolicy=perceptual&quality=mediumHigh&hash=ca9d74f80b8c6d93f82ed89006da219c11f9c62781de956f8b84d85db2d5c584)