There’s no silver bullet when it comes to managing flood risk and damage, but using a variety of tactics over time could help. That’s what the City of Courtenay is doing as part of its flood management plan to protect infrastructure and homes as climate change-related flood events become more frequent and severe.

The City of Courtenay was built alongside the Courtenay River, with many low-lying sections of the city situated within the river’s floodplain. Floodplains are areas adjacent to a river or moving water, and their geography places them at high risk for flooding and erosion.

Floodplains provide rich soil that supports agriculture, but building so close to (and within) one also puts areas of the city at risk when flood events — which have occurred throughout history and are becoming more severe as the climate changes — take place.

The river and its surrounding lands have been stewarded for thousands of years by ancestors of the K’ómoks First Nation — descendants of the Sathloot, Sasitla, Ieeksen, Xa’xe and Pentlatch. Many surrounding areas get their namesake from the Éy7á7juuthem, Kwak̓wala, and Pəntl’áč languages — including the Puntledge River and the Tsolum River.

Prior to the arrival of settlers, the Courtenay River meandered into its tributaries and floodplains as water levels changed throughout the seasons. But it has since been choked by various man-made walls or structures, and much of the surrounding vegetation has been removed to support industry. In recent years, extreme precipitation, storm surge and sea level rise have also increased flood risk to the City of Courtenay. As a response, the city is working with consultants to understand the risk of flood to the community and come up with strategies to reduce risk.

“We don’t want to fight the flood water,” said Jeanienne Tazzioli, the City of Courtenay’s manager of environmental engineering. “We want to ensure that our infrastructure is designed for the flood risk that we face in the future.”

She added that this includes shoring up buildings as well as making sure roadways and the city’s sanitary lift stations — pumping stations that move wastewater from lower elevations to higher elevations — are functioning amidst floods so people don’t lose those services.

Although the City of Courtenay can’t predict exactly how flooding will impact it in the future, it has spent time looking at past events, different climate models and other flood plans to try and understand what future flood events may look like and mitigate them.

How to plan for future flood events

A state of emergency was declared in both 2009 and 2014 due to heavy rains and flooding that caused bridge closures and evacuations in the community. More recently, the demolition announcement of the Anderton Arms apartment building due to erosion and flood risk highlights the consequences of constructing buildings that are not designed to withstand environmental risks.

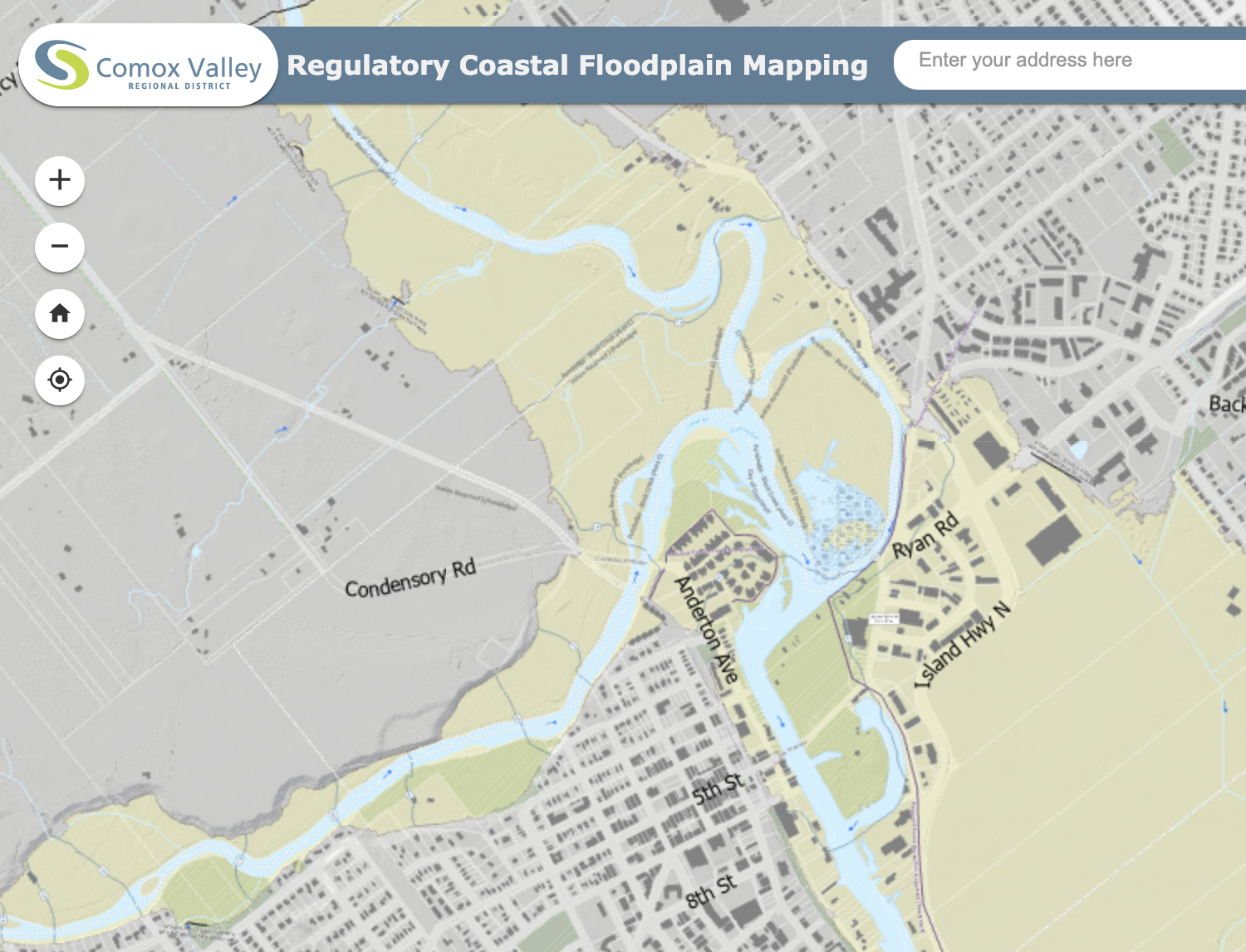

In 2023, Courtenay announced it would be developing a flood management plan. The plan was built on the bones of the City of Courtenay’s Official Community Plan, the CVRD’s Coastal Flood Adaptation Strategy from 2021 and regulatory flood maps — maps that are used to guide land use decisions and enforce local floodplain management bylaws based on projections of various flooding scenarios.

These scenarios are based on different climate models, which are computer simulations of the Earth’s climate system and how it changes over time, according to the MIT Climate Portal. Since different levels of sea level rise and atmospheric changes will result in different flooding scenarios, it’s tricky to predict the most likely future, so the CVRD needs to consider various options.

“[The CVRD] looked at a bunch of different scenarios,” Tazzioli said. “There are scenarios that consider different levels of sea level rise and different amounts of rainfall. We don’t know what the future holds, we can just model different scenarios.”

After looking at dozens of scenarios, the CVRD landed on creating a floodplain map based on a sea level rise of one metre, and a rainfall event that has a 0.5 per cent chance of happening at any given year. Tazzioli said mathematically, this part often gets confused. It means that this rainfall event has a one in 200 year probability, but it is important to understand that just because the probability is a one in 200 year chance, it could happen at any given time — not every 200 years.

The one metre sea level rise is also hard to predict. It is often estimated to occur in the year 2100 for the area, Tazzioli said. But she added that this is based on assumed rates of warming, and that warming is now happening faster than was previously expected, so it may be sooner.

“We don’t [exactly] know when that will happen. That is the little asterisk,” Tazzioli said.

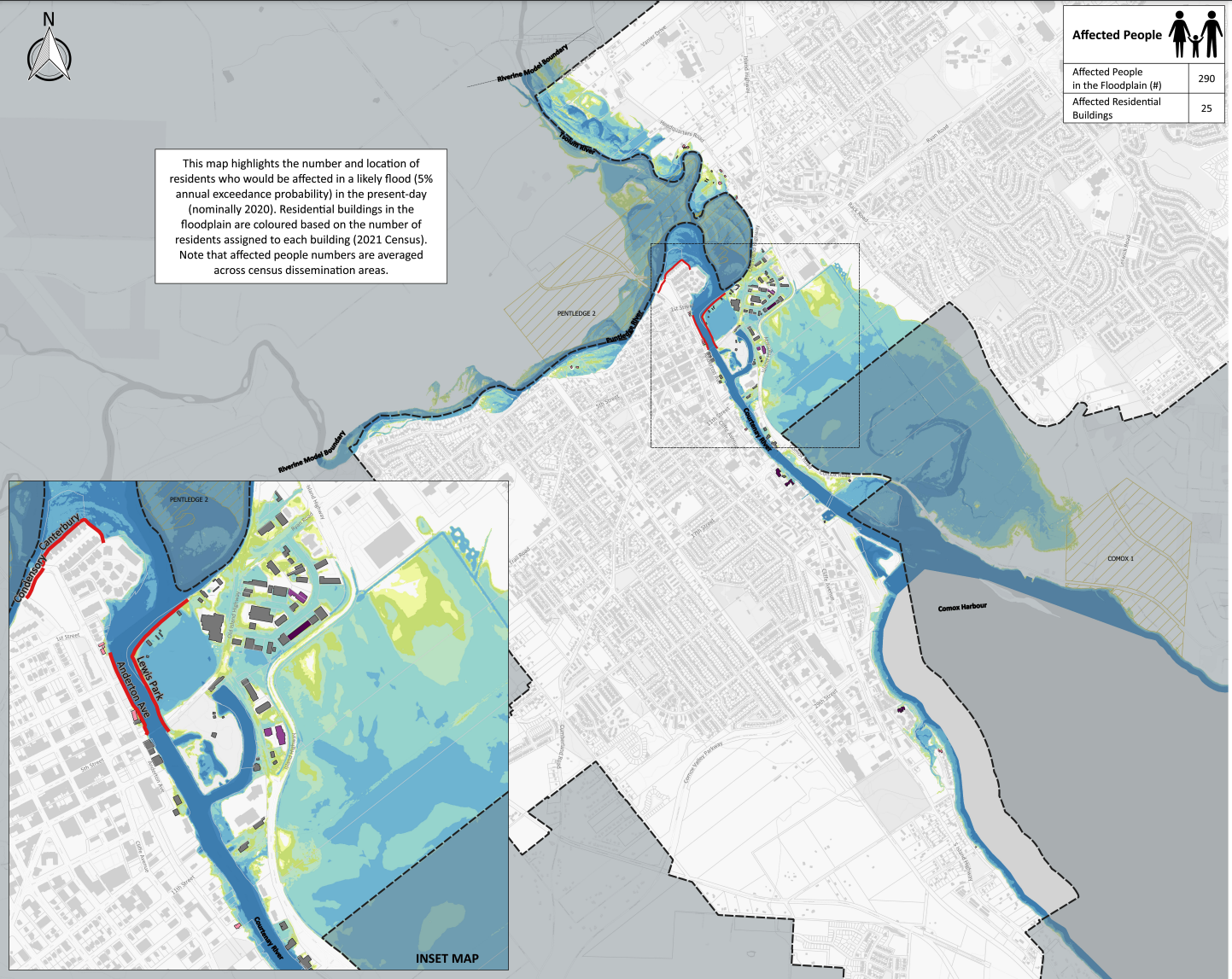

The uncertainty of future flood events led the City to create more than one flood map. Tazzioli said the city created a set of consequence maps for two different scenarios to illustrate the impacts of flooding on people and culture, buildings and infrastructure, the economy and the environment. The maps it came up with represent flood risk placed in the present day, with a one in 20 year rainfall event, as well as the risk of a future flood event, with one metre of sea level rise. The future risk map showcases the worst case scenario, something that would be considered a rare event.

Screenshot of a likely present-day flooding scenario. For more information and all of the flood consequence maps, visit https://www.courtenay.ca/EN/main/city-hall/projects-gallery/flood-management-plan/flood-consequence-maps.html . Screenshot/City of Courtenay

“Although we want to be aware of that rare event, it’s kind of like that worst case scenario, but because there’s so much uncertainty, we would like to have some perspective on what that could look like,” Tazzioli said.

The floodplain boundary is fuzzy

Tazzioli said one of the difficulties while planning for flood risk is that the floodplain boundary isn’t always clear. It depends on different scenarios.

Instead, it is a series of likelihoods. Some of these areas include a floodway and a flood fringe.

The floodway is a section where the likelihood of flooding is the greatest. The flood fringe is the area on the edge of the floodplain that floods less often and may flood with less depth and speed.

“People will [ask], am I in the floodplain, or not? Like, black or white? But the floodplain boundary is fuzzy, it’s gray.,” Tazzioli said.

“We could have flood events that are smaller, we could have flood events that are more severe, it’s simply just an estimate of the scenario.”

A section of the CVRD’s regulatory coastal flood mapping, with floodplain areas shown in yellow. Screenshot/Comox Valley Regional District

There is no plan that will address every scenario at the same time, but the City has five different strategies for flood response: avoid, retreat, protect, build resilience and accommodate the flood waters.

“In areas where maybe they remain undeveloped and there’s no hard insurance, we want to avoid development that would increase the risk,” she said.

Retreat, she said, could happen in areas that have faced a high risk — such as where Anderton Arms is located along the Courtenay River.

“We could [also] protect things, trying to keep them dry. That’s mostly applicable on a small scale, like a lift station or a pump station,” Tazzioli said. “Then there’s the resilience building, so getting ready for an emergency, making sure people are prepared [and] they know what to do.”

And finally, she said the city can accommodate and design its infrastructure and amenities within the hazard areas to accommodate the flood waters and reduce damage.

“Those five tools used on different time scales address that flood risk,” Tazzioli said.

Those living anywhere within the Comox Valley Regional District can take a look at the CVRD’s Regulatory Coastal Flood Map to see if their homes or businesses are located within the floodplain boundary. More information can be found on the CVRD website, including the PDF of the final report.

For residents within the City of Courtenay’s limits, resources to reduce flood risk and build property flood resilience are on its website under its Flood Management Plan. There is also a page to view the flood consequence maps and a FAQ page.

People take pictures along Dallas Rd. as strong wind warnings are issued by Environment Canada along the south coast as a frontal system pushes across Vancouver Island during the first major storm of the year in Victoria, Tuesday, Jan. 5, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Chad Hipolito