Pump and dump schemes in traditional finance are quite simple: Holders of a tradable asset, such as stock in a company, will heavily hype and promote the asset to other investors, often using misleading statements, causing the price to rise rapidly as new investors buy . The holders will then sell their overvalued shares at a profit, causing the price to plummet, leaving the newer investors stuck with a low-value asset.

Unfortunately, pump and dump schemes have also become common in the crypto world. This is largely due to the relative ease with which bad actors can launch a new token and establish an artificially high price and market capitalization for it “on paper” by seeding the initial trading volume and controlling the circulating supply. Additionally, teams launching new projects and tokens can remain anonymous, which makes it possible for serial offenders to carry out multiple pump and dump schemes.

What is a crypto pump and dump scheme?

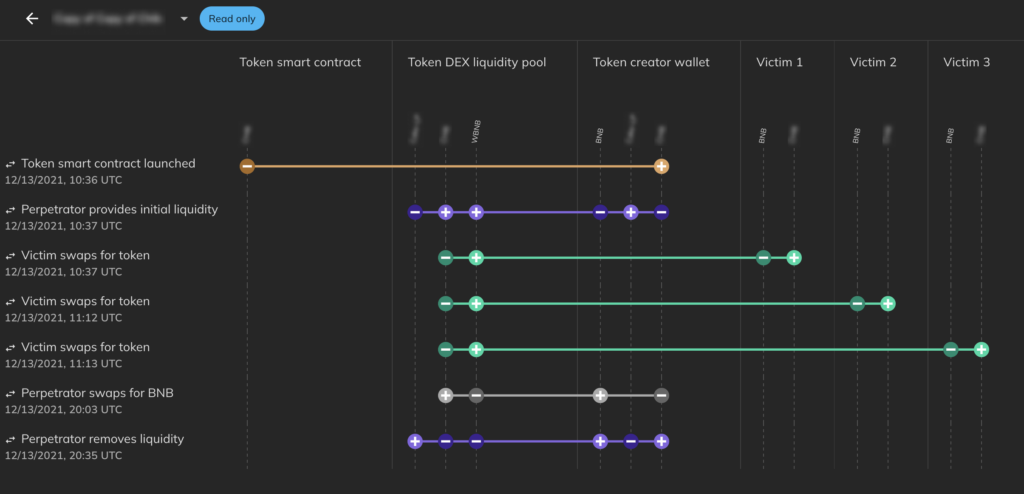

We can see an example of what a typical crypto pump and dump scheme looks like on-chain below in Chainalysis Storyline, using an undisclosed token example. The token bears all the telltale signs of a pump and dump scheme, with the asset’s price dropping 90% in the first week of trading following the token creator dumping their holdings.

The token provides a good model for how pump and dump tokens work. The creator launched this token’s smart contract and funded a new liquidity pool for it on a popular decentralized exchange (DEX) in December 2021, after promoting the launch to crypto enthusiasts on social media. Hundreds of victims bought the token on that DEX, allowing the price to rise quickly in a matter of hours. However, within the same day of launch, the creator sold off all of his tokens, leaving buyers holding the bag. Overall, the fraudster made just under $20,000.

Below, we attempt to quantify the scale of pump and dump schemes in cryptocurrency by analyzing all tokens launched on the Ethereum and BNB blockchains in 2022. While more than 1.1 million tokens were launched last year, the vast majority got virtually no traction, as measured by the frequency of swapping happening on DEXes. Since we want to focus on projects that had an impact on the crypto ecosystem, we’ll only count tokens that achieved a minimum of ten swaps and four consecutive days of trading in the week following their launch. With that criteria in place, the number of new tokens falls from 1.1 million to 40,521.

The next criteria we’ll look for is a drastic price decline of 90% or more in the first week of trading, which could suggest the token’s originators and earliest holders dumped the token extremely quickly, making it a relatively strict standard for assessing a token as a possible pump and dump. Of the 40,521 tokens launched in 2022 that gained sufficient traction to be worth analyzing, 9,902, or 24%, saw a price decline in the first week indicative of possible pump and dump activity.

| Number of tokens | Percent of all tokens launched | |

| Total tokens launched | 1,105,239 | 100.0% |

| Tokens with over 10 swaps and 4 consecutive trading days in first week after launch | 40,521 | 3.7% |

| Tokens with a 90% price drop in first week after launch | 9.902 | 0.9% (24% of tokens that got traction) |

It’s possible, of course, that in some cases, teams involved with token launches did their best to form a healthy offering, and the subsequent drop in price was simply due to market forces and challenges stemming from less established infrastructure for market creation in the digital asset space. While it’s impossible to know the promotional strategy or intentions behind all 9,902 tokens, we did check the 25 with the biggest first-week price drop on Token Sniffer, a service that scores new tokens on a scale of zero to 100 based on their trustworthiness and docks points for any scam-like characteristics. According to Token Sniffer, those 25 tokens all scored zero, indicating that, according to Token Sniffer’s evaluation criteria, they were almost certainly designed for a pump and dump. Token Sniffer also found that many of them contained malicious “honeypot” code that prevents new buyers from selling the token — one of the surest possible signs that the coin is part of a pump and dump scheme.

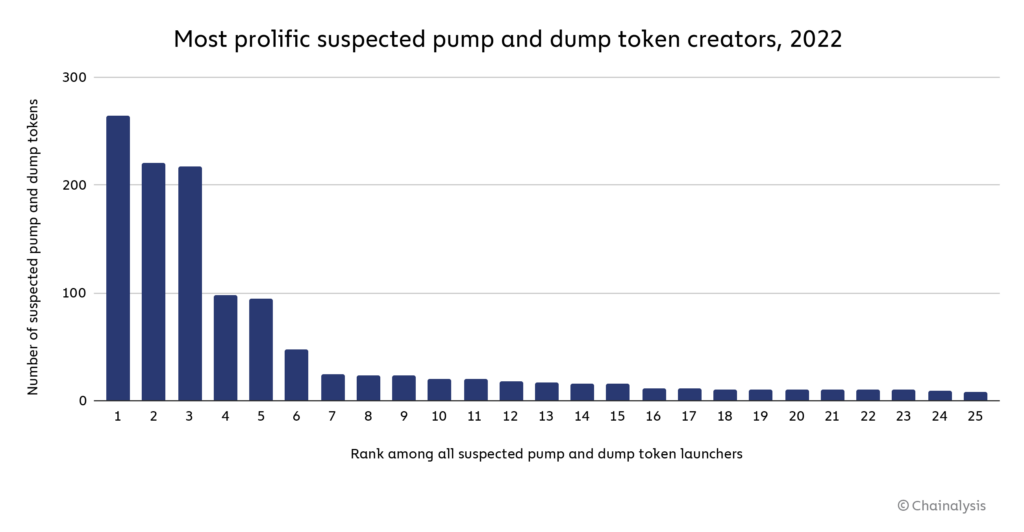

In total, buyers not believed to be associated with the tokens’ creators spent a total of $4.6 billion worth of cryptocurrency acquiring some of the 9,902 suspected pump and dump tokens we identified — a relatively trivial amount compared to the trillions in crypto transaction volume in 2022 , but still a substantial amount of damage for unsuspecting investors. We estimate that the creators of these tokens made a total of $30 million in profits from selling off their holdings before the tokens’ value plummeted. In many cases, the same wallet provided initial liquidity for several tokens that fit our pump and dump criteria, or provided funding to the wallet that did, suggesting those wallets share common ownership. Using this methodology, we found that 445 individuals or groups accounted for 24% of the 9,902 suspected pump and dump tokens launched in 2022.

The most prolific suspected pump and dump token creator we identified launched 264 tokens that fit our criteria in 2022.

Pump and dump schemes are uniquely destructive in the cryptocurrency world due to the ease with which new tokens can be launched and the social media-driven nature of crypto investment news and discussion. Many believe that cryptocurrency is approaching an inflection point that could spark mass adoption, but that could be difficult if the general public perceives cryptocurrency as rife with pump and dump schemes designed to prey on newcomers. We look forward to working with our partners in both the public and private sectors to investigate this activity and build a safer ecosystem in the future.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.

;Resize=(1200,627)&impolicy=perceptual&quality=medium&hash=f92cb3aa039d259b3900c03535e48bf63612cf4dcf8d920eb7ff0197d007c4f4)