Cellular agriculture – the production of meat from cells grown in bioreactors rather than harvested from farm animals – is taking leaps in technology that are making it a more viable option for the food industry. One such leap has now been made at the Tufts University Center for Cellular Agriculture (TUCCA), led by David Kaplan, Stern Family Professor of Engineering, in which researchers have created bovine (beef) muscle cells that produce their own growth factors, a step that can significantly cut costs of production.

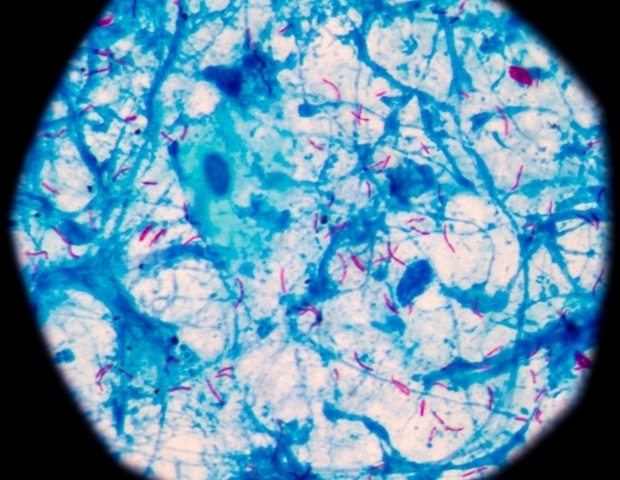

Growth factors, whether used in laboratory experiments or for cultivated meat, bind to receptors on the cell surface and provide a signal for cells to grow and differentiate into mature cells of different types. In this study published in the journal Cell Reports Sustainability, researchers modified stem cells to produce their own fibroblast growth factor (FGF) which triggers growth of skeletal muscle cells – the kind one finds in a steak or hamburger.

FGF is not exactly a nutrient. It’s more like an instruction for the cells to behave in a certain way. What we did was engineer bovine muscle stem cells to produce these growth factors and turn on the signaling pathways themselves.”

Andrew Stout, then lead researcher on the project and now Director of Science at Tufts Cellular Agriculture Commercialization Lab

Until now, growth factors had to be added to the surrounding liquid, or media. Made from recombinant protein and sold by industrial suppliers, growth factors contribute to a majority of the cost of production for cultivated meat (up to or above 90%). Since the growth factors don’t last long in the cell culture media, they also have to be replenished every few days. This limits the ability to provide an affordable product to consumers. Taking that ingredient out of the growth media leads to an enormous cost savings.

Stout is leading several research projects at Tufts University Cellular Agriculture Commercialization Lab -;a technology incubator space which is set up to take innovations at the university and develop them to the point at which they can be applied at an industrial scale in a commercial setting.

“While we significantly cut the cost of media, there is still some optimization that needs to be done to make it industry-ready,” said Stout. “We did see slower growth with the engineered cells, but I think we can overcome that.” Strategies may include changing the level and timing of expression of FGF in the cell or altering other cell growth pathways. “In this strategy, we’re not adding foreign genes to the cell, just editing and expressing genes that are already there” to see if they can improve growth of the muscle cells for meat production. That approach could also lead to simpler regulatory approval of the ultimate food product, since regulation is more stringent for addition of foreign genes vs editing of native genes.

Will the strategy work for other types of meat, like chicken, pork, or fish? Stout thinks so. “All muscle cells and many other cell types typically rely on FGF to grow,” said Stout. He envisions the approach will be applied to other meats, although there may be variability for the best growth factors to express in different species.

“Work is continuing at TUCCA and elsewhere to improve cultivated meat technology,” said Kaplan, “including exploring ways to reduce the cost of nutrients in the growth media, and improving the texture, taste, and nutritional content of the meat. Products have already been awarded regulatory approval for consumption in the U.S. and globally, although costs and availability remain limiting. I think advances like this will bring us much closer to seeing affordable cultivated meat in our local supermarkets within the next few years.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Stout, A. J., et al. (2024). Engineered autocrine signaling eliminates muscle cell FGF2 requirements for cultured meat production. Cell Reports Sustainability. doi.org/10.1016/j.crsus.2023.100009.